Heavy human use of the marine environment has left our seas in a poor condition. Commercial fishing has been practiced in Europe for over 1000 years and with the advent of industrial fishing the pressure on our oceans has been scaled up dramatically. Aquaculture, agriculture, oil and gas exploration, renewable energy, plastic pollution and noise pollution are all ways in which we are putting additional pressure on the ocean every day. The good news is that some of these activities can be managed through a well thought-out marine spatial plan. The plan must take into account the location of vulnerable ecosystems and ensure they are protected in a well-connected and managed network of areas which are set aside for the sole purpose of active conservation and, in some cases, restoration efforts. Ireland’s first marine spatial plan is due to be published in late 2020.

Marine protected areas (MPAs) are a proven tool to provide much needed ecosystem restoration and even contribute to sustainable fishing and climate change mitigation. They are safe havens for animals and plants to grow and reproduce without the threat of damaging human activities. Such havens are vital if marine ecosystems are to withstand all the additional pressures they face day to day, such as rising temperatures and ocean acidification.

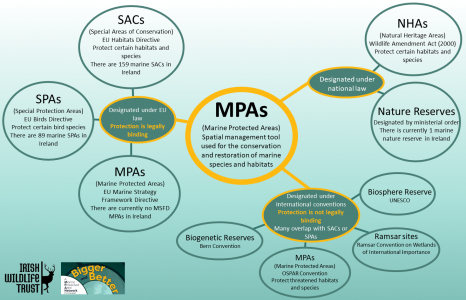

Ireland has not yet legally defined what the term MPA means. We do however have two types of protected sites that would fit the IUCN’s definition, namely Special Areas of Conservation designated under the Habitats Directive and Special Protection Areas designated under the Birds Directive. These sites combined form the so-called Natura 2000 network, a Europe-wide network of sites that protect certain terrestrial and marine habitats and species. More info on these sites in Ireland can be found here.

There is a third type of European legislation which calls for the designation of MPAs in order to bring the marine environment to an overall good environmental status – the Marine Strategy Framework Directive. We can expect MPAs to be designated under this directive in Ireland over the next few years.

It is important to note that not all MPAs are created equal. They are spatial management measures used to protect certain habitats or species, which means that not all human activities are automatically excluded from any MPA. Only those activities that may be harmful to the particular protected habitat or species must be excluded from the site. Here are the six different MPA categories according to the IUCN that range from strict no-take zones (i.e. no fishing or other extractive activities) to multi-use sites that allow some extractive activities:

Category I – Protected area managed mainly for science or wilderness protection (Strict Nature Reserve/Wilderness Area);

Category II – Protected area managed mainly for ecosystem protection and recreation (National Park);

Category III – Protected area managed mainly for conservation of specific natural features (Natural Monument);

Category IV – Protected area managed mainly for conservation through management intervention (Habitat/Species Management Area);

Category V – Protected area managed mainly for landscape/seascape conservation and recreation (Protected Landscape/Seascape);

Category VI – Protected area managed mainly for the sustainable use of natural ecosystems (Managed Resource Protected Area).

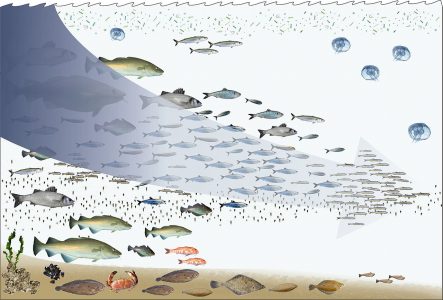

Fishing down the food web, a North Sea perspective. Inspired by the work of Daniel Pauly. © Hans Hillewaert

Decades of fishing with trawls and dredges have resulted in widespread destruction of benthic habitats, while large predatory fish have declined by an estimated 90% since the beginning of industrial fishing. However, sealife has remarkable resilience and the ability to bounce back quickly once main pressures are removed. Scientists worldwide agree that a coherent network of MPAs under strict management can be a helpful tool to combat environmental degradation caused by fishing and other extractive activities, as well as increase the resilience of marine habitats to better cope with other stressors that lie beyond MPA boundaries.

Strict protection of even the most highly impacted places has resulted in significant increases in biodiversity over relatively short time frames. From sessile animals like sponges or corals to highly mobile fish species, many organisms benefit from a balanced ecosystem where they can feed and reproduce in peace.

Seagrass bed in Bantry Bay, Cork.

© Regina Classen

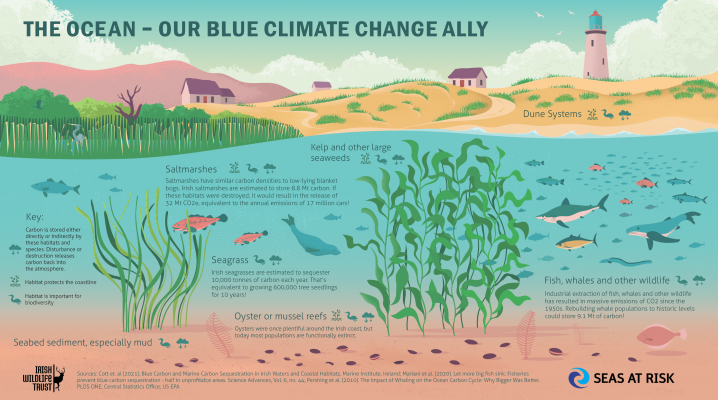

Climate change mitigation: MPAs can play a crucial, low cost role in the mitigation of climate change.

Strict protection of habitats that are very rich in carbon (e.g. seagrass, kelp) can prevent a rise in new emissions which would otherwise result from loss or degradation of these areas. Restoration of habitats that were already lost and ensuring they are well protected could contribute significantly to additional carbon storage in our seas. In surveys conducted by the National Parks and Wildlife Service in recent years, 52% of the protected habitat ‘large shallow inlets and bays’ was classed as bad mostly due to total or partial loss of seagrass habitat. Removing the pressures on this habitat type is a vital first step to ensure Ireland’s biodiversity and climate goals are met.

Climate change adaptation: Restoration and protection of coastal saltmarsh, kelp forests, or oyster and mussel reefs, can help reduce the impact of storms and coastal flooding, thereby reducing the need for hard engineering. Networks of protected areas may act as stepping stones for species as they move towards polar regions in response to rising temperatures. Furthermore, due to improved ecosystem health within MPAs, habitats become more resilient in the face of climate change and pollution.

The infographic shows the importance of protecting marine biodiversity to enhance carbon storage in our seas.

Image by Kieran Boyce

MPAs lead to changes in population structure in ways that promote replenishment. In one study, biomass of all trophic fish groups (predator and prey) has been shown to increase significantly (between 40%-200%) in no-take marine reserves. As the animals within the reserve grow larger over time, they also produce more eggs, are more successful at reproduction and produce fitter young. Target species with low mobility such as scallops and lobsters are found to profit substantially from no-take zones in the UK. Dive surveys carried out in Lamlash Bay, a community-led marine reserve, showed significant increases in catch per unit effort (109%), weight per unit effort (189%) and carapace length (10-15 mm) of the European lobster Hommarus gammarus. Furthermore, scientists found twice as many berried lobsters within the reserve compared to outside, which shows that the reserve has a positive impact on productivity.

A grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) pup rests on a bed of seaweeds (credit Scotlandbigpicture.com).

A 2020 study found that we can rebuild marine life by 2050 if we take some drastic measures, including scaling up protection to cover 30% of our ocean by 2030 and increase restoration efforts of some key habitats: Saltmarshes, seagrass, kelp, and oyster reefs (among others). These are common habitats found in Ireland and the restoration of these will be crucial to rebuild ecosystems. Restoration efforts alone will not be enough, however. We need better fisheries management, tackle pollution issues and markedly reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to rebuild ocean life to its former glory.

Most countries have signed up to the Convention on Biological Diversity, agreeing to protect 10% of their waters by 2020 and most countries are now on course to protecting 30% by 2030.

Ireland has currently designated only 8.1% of their marine waters as MPAs (in form of SACs and SPAs) meaning we have a long way to go to get to the proposed 30% by 2030. We are currently working to get new ambitious MPA legislation which will hopefully be enshrined into Irish law by the end of the year.

Most MPAs in Ireland are not very good examples of the type of protected area needed to restore ocean life. Many harmful human activities are still taking place inside MPAs with little or no management or enforcement. As a result, marine habitats are deteriorating with losses of seagrass and functional extinction of oyster reefs evident around the country, mostly due to easily managed activities such as fishing and aquaculture, or agricultural and sewage pollution.