by Pádraic Fogarty, January 22nd 2022

Forestry continues to be a vexed issue in Ireland. While the forest owners, nurseries, sawmill owners and timber suppliers are mostly focussed on the immediate issues of getting licences for planting and felling, the bigger, and more important issue is the lack of new forest establishment. In fact, due to planned felling over the coming decade, Ireland is set to suffer net deforestation – something nobody with an interest in trees wants. Speaking to the Oireachtas committee on Environment and Climate Action last week, the chair of the Climate Change Advisory Council, Maria Donnelly, said she was “shocked” at this state of affairs and that reversing this “is one of the highest policy priorities on our agenda at the moment.”

Despite the acknowledged crisis, forestry is still moving in the wrong direction with continued planting of Sitka Spruce monocultures, including on peatlands, and the tragic granting of a forestry licence on one of the last Hen Harrier nest sites in Co. Cork. As Minister Pippa Hackett’s ‘Project Woodland’ enters its second year, there is no shortage of frustration. Yet, there is an opportunity this year, with a soon to be announced public consultation, a new Forest Strategy and an accompanying Forest Programme, and it’s vitally important that we get these right. The challenge ahead is daunting, but there are places that have faced a similar challenge in the past, and from which we should learn.

Costa Rica is a county only slightly smaller than Ireland and with a more or less similar population (4.5 million). The tropical Central American country has stood out for a number of years, being peaceful in an unstable region, relatively prosperous, open to foreign direct investment (like Ireland is hosts multinational tech companies such as Intel) and a bucket list destination for nature-loving tourists. I visited the country in 2009.

But recently, Costa Rica has basked in a reputation for enjoying social and economic development while protecting and restoring its natural environment. In 2015 it pledged to be fully decarbonised by 2050 (not just ‘net zero’) while at COP26 in Glasgow last year it was the darling country: leading global efforts to protect 30% of land and sea by 2030 and actually putting this into practice. By the end of 2021 it had announced that an expansion of its Marine Protected Area network will now meet the 30% threshold while its environment minister said at the announcement that “the key in the end is to understand that this is one more milestone, many things have to be complemented, we are not talking about a paper park, we do not intend that, what we want is for it to be a national park and a marine management area that they are going to work properly in a comprehensive way”.

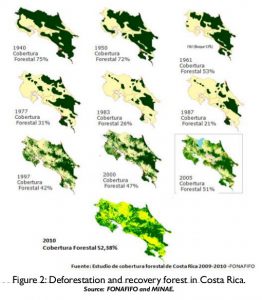

In 2021 Costa Rica was among the inaugural winners of the Earthshot Prize, for its epic reforestation. And this is the bit that should interest us here in Ireland. Like Ireland, Costa Rica is a country that is naturally clothed in rainforest although they only began to lose theirs in the 20th Century. While deforestation in Ireland was more or less complete by the 1700s in Ireland, Costa Rica saw a fall in natural forest cover from 75% to 21% between 1940 and 1987. In the 1990s it was felling 45,000 hectares of virgin rainforest every year, among the worst rates of deforestation in the world at that time. But by 2020 forests covered 60% of the total land area. How did Costa Rica triple its forest cover in a mere 30 years?

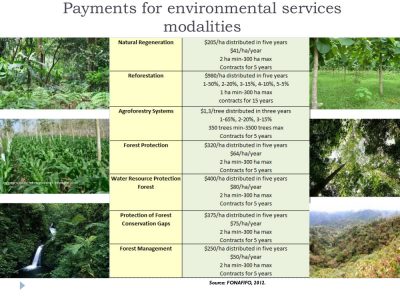

The short answer is that it recognised the problem and pioneered a system of ‘payments for ecosystem services’. In other words, paying farmers to switch from agriculture to forests. An ‘Environmental Services Payment Programme’ was launched in 1997 and was directed at small and medium sized landowners. 80% of the financing was raised through a tax on fossil fuels while the remainder raised from private sources, e.g. the voluntary carbon markets. The system recognised the range of approaches that were needed to reforest the country including protecting and manging existing forests, protecting water sources, expanding forests through natural regeneration and tree planting as well as timber plantations and agroforestry. Tourism has been critical to the development of the rural economy and today (or at least until the arrival of Covid) Costa Rica is among the leading destinations for eco-tourism in the world.

From what I can tell, the extraordinary increase in tree cover in Costa Rica has been natural forests although it is frustratingly difficult to confirm this given that the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (and other international reporting bodies) do not distinguish between primary forest, newish but natural forests and monoculture plantations (the UN however does report that nearly all of the forest restoration in Latin America between 2000 and 2010 was from natural regeneration or ‘active ecological restoration’, in contrast to south-east Asia where about two-thirds was from ‘plantations or woodlots’). At least one protected area, the Santa Rosa National Park, established in 1971, has been established on former grazing land and is now recovering jungle.

It is also important to emphasise that secondary forest, that is, the vegetation that regrows after trees have been felled, is no substitute for preserving the original, primary rainforest. The biodiversity is typically much lower and will take many decades, or centuries to fully recover. This is a lesson we have yet to learn in Ireland where even the tiny remnants of our old, natural forests are not protected – despite being treasure troves of biodiversity.

There are no doubt significant cultural differences between farmers in Costa Rica and those in Ireland as we have a much longer tradition of pastoral agriculture. Plus, there is precious little connection in Ireland to our forest heritage, given the length of time since the woodlands were cleared. Deforestation in Costa Rica effectively happened over a single lifetime.

Nevertheless, I hope we can learn the important lessons on offer. Primarily, that nature is quick to recover when given a chance. All other things being equal, there is no reason why Ireland could not achieve 40% or more of forest cover by 2050. But equally important is getting the incentives right for landowners to respond. The last decade of Irish policy shows that this is not just about money. Subsidies on offer for Sitka Spruce plantations have been extremely generous and yet planting rates remain low. Communities, not only landowners, will need to feel listened to and be given a meaningful say in the establishment of future forests. We will need to rediscover the many values associated with being forest people.