2023 saw the publication of the “Report of the Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity Loss”. Many impactful solutions to biodiversity loss are found within the recommendations of the Citizens’ Assembly. It is vital that the Government of Ireland act on these recommendations. This series of articles explores ideas found within the Citizens’ Assembly recommendations. This article first appeared in 2024 Irish Wildlife magazine spring issue. Get your copy of the latest Irish Wildlife magazine by joining the IWT today.

In this article Pádraic Fogarty examines the Citizens’ Assembly’s recommendation that “the 1945 Arterial Drainage Act is no longer fit for purpose and must be reviewed and updated in order to take proper account of the biodiversity and the climate crisis”. The opinions expressed in this article represent those of the author and do not neccessarily represent the views of the Irish Wildlife Trust.

By Padraic Fogarty

First published online: January 2025

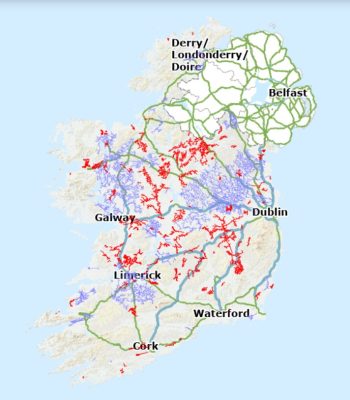

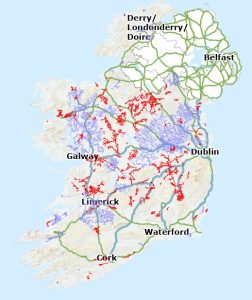

Map showing the extent of river drainage in Ireland. Drainage Districts Channels (red) and Arterial Drainage Scheme Channels (purple) both sets of channels are maintained under the Arterial Drainage Act. Source www.floodinfo.ie

How many of us know what a river looks like? This may sound like a ridiculous question but on a trip to Albania last year I found myself looking at a river and thinking: we have nothing like this at home! In school we learned that rivers rise in the mountains, where they flow quickly and their waters are clear and full of oxygen. When reaching the lowlands they slow down, meandering and sometimes spilling out onto lateral plains. We learned about ox-bow lakes, where the meander in the river widens so much that the river cuts it off entirely. Flooding, meandering and an ever-shifting pattern of wetlands that lie away from the main channel of flowing water are natural features of rivers, but they have been virtually erased from the Irish landscape. I don’t think I’ve ever seen an ox bow lake in Ireland!

This is, in large part, due to the Arterial Drainage Act (ADA), a piece of legislation from 1945 that used public money for the straightening and deepening of rivers in order to create more productive farmland. The river I was looking at in the Theth National Park, in the north of Albania, was in the mountains. But here the path of the river was broad, with gravel islands and what is referred to as a braided channel: lots of little channels and standing water that interweave with one another. And trees, lots of trees. Leaning out over the edge of the river, piled up logs that have been swept downstream, masses of woody debris and emerging scrub of willows and other plants on the islands.

In lowlands too, river margins are naturally wooded and this is an integral component of river dynamics. Fallen trees divert the energy out of flowing water, creating pools which are sanctuaries for fish. The increased energy elsewhere helps to scour gravel beds which are needed for many fish to spawn in. The volume of woody material in natural rivers provides food for abundant invertebrates and so forms the foundation for levels higher up in the food chain. In Ireland, the extent of deforestation stretches right to the water’s edge; most rivers now have no, or very few trees, while trees in rivers are seen as a threat to life and property and so are quickly ‘cleaned’ away.

The result is that rivers in Ireland, whether in the uplands or lowlands, have been so physically altered that they are very, very far from their natural state (never mind the added burden of pollution). The physical condition of a river is referred to as its ‘hydromorphology’ and has been identified by the Environmental Protection Agency as one of the leading reasons why water bodies are failing to reach ‘good status’ as required under the EU’s Water Framework Directive. In essence, we don’t know what a natural river looks like because examples scarcely exist in Ireland.

A rare example of a tree (a willow) growing naturally on a river bank showing how it creates a network of sheltered pools. River Liffey. Photo by Pádriac Fogarty.

A river’s hydromorphology is severely affected by the imposition of dams and weirs which block the movement of water along its direction of flow. Where rivers have been subjected to deepening and widening, frequently using the excavated material to raise the height of the riverbank, the water is blocked from moving laterally, rather like a straightjacket. This is known as arterial drainage. It not only greatly diminishes the habitat diversity of the river, with knock on consequences for biodiversity, it also prevents the energy and water volume of the rivers from diffusing and so, at times of flood, the energy surges downstream, increasing the risk of flooding in those areas.

The ADA was passed at a time of food shortages across Europe, poverty at home and little to no appreciation of ecology or the damage that it was causing. Nearly 80 years on, priorities and our understanding of river dynamics have greatly increased. So too has the threat to communities from extreme weather events, whether heavy and violent rainfall, or drought. But the ADA remains largely unchanged, and the Office of Public Works is legally obliged to ‘maintain’ 11,500km of rivers that have been subjected to arterial drainage. This means periodically going back with diggers to clear out any accumulation of silt or remove trees and vegetation. While these works are subject to environmental assessment, the baseline against which impacts are measured is the already severely degraded river, and so the process usually sails through with no significant impacts predicted.

The River Boyne system showing straightening, deepening and total removal of riparian vegetation. Photo by Pádriac Fogarty.

Criticism of the ADA is not new. The damage to fisheries became apparent quite quickly and there were calls to minimise the environmental impacts. When the River Boyne in Co Meath was dredged in the 1980s one prominent ecologist pleaded with authorities to at least leave the vegetation intact on one side of the river. But to no avail. The approach today remains brutal and uncompromising.

In 2021, the Irish Wildlife Trust launched a campaign to reform the ADA. This included gathering over 5,000 signatures to a petition addressed to the then-minister in charge of the OPW, Patrick O’Donovan. The good news is that this work, and the work of other NGOs, including the Sustainable Water Network (SWAN), paid off.

In 2022, the Citizens’ Assembly on biodiversity loss said that “the 1945 Arterial Drainage Act is no longer fit for purpose and must be reviewed and updated in order to take proper account of the biodiversity and the climate crisis”. In December 2023, the Joint Oireachtas Committee on Environment and Climate Action, reflecting on the recommendation of the Citizens’ Assembly, demanded that “the Arterial Drainage Act 1945 be urgently reviewed and amended to align with national and EU laws and objectives to protect, promote and enhance biodiversity.” Earlier this year, the government published the Water Action Plan 2024, which is the third River Basin Management Plan that sets out to achieve the objectives of the Water Framework Directive. It’s far from a perfect plan but it does highlight the issues with the ADA and says that “A review of arterial drainage requirements and the underpinning Arterial Drainage Act will be undertaken in order to inform future land use policy decisions arising out of the Land Use Review and to support the preparations for the implementation of the new Nature Restoration Law and the Heavily Modified Water Body review process.”

So after years of campaigning, it is now official government policy to reform the ADA. This is an achievement. However, given the slow pace at which the government moves on these issues, not to mention that a new government in 2025 will inevitably lead to a shake up of priorities, we are still very far from seeing change on the ground. We have to hope that whatever the makeup of the new government, there will be individuals or parties willing to fight to include reform of the ADA in the next programme for government. If it’s not there, it won’t happen.

The reason why reform of the ADA is difficult is that it will require the return of farmland that benefited from drainage to the river. Rivers need space and that brings restoration into direct conflict with other land use priorities. Overcoming this should not be difficult, at least in theory. Farm payments need to be decoupled from food production. Some progress has been made on this during this government, in so far that farmers are no longer penalised for having land which is not in agricultural production. So, a farmer with a flooded field doesn’t lose a chunk of their direct payment, which was the case previously. However, a field underwater is a field that is not capable of feeding animals or producing crops, so the balance of costs is still against the farmers. This has to change.

The reason why reform of the ADA is difficult is that it will require the return of farmland that benefited from drainage to the river. Rivers need space and that brings restoration into direct conflict with other land use priorities. Overcoming this should not be difficult, at least in theory. Farm payments need to be decoupled from food production. Some progress has been made on this during this government, in so far that farmers are no longer penalised for having land which is not in agricultural production. So, a farmer with a flooded field doesn’t lose a chunk of their direct payment, which was the case previously. However, a field underwater is a field that is not capable of feeding animals or producing crops, so the balance of costs is still against the farmers. This has to change.

Farmers that give land to nature are providing a service to the rest of us and so need to be rewarded and incentivised. The mechanisms for this are not yet in place and we may need to wait for another reform of the Common Agricultural Policy, or the appearance of a new pot of EU money solely dedicated to nature restoration (something that has been promised). The process as it stands is moving in the right direction but at such a slow pace that we are being overwhelmed with the rate of change in nature itself.

The River Nore showing the near absence of trees and natural vegetation along its banks. Photo by Pádriac Fogarty.

The work to restore rivers itself is not complicated. Dams and barriers need to be removed although those protecting towns and cities probably will have to stay. Skilled digger drivers can reprofile riverbanks to something more like their natural state, rather like what is being done for bog restoration programmes. Broad river corridors should be established where rewilding principals can be applied: let trees naturally regenerate, let hollows of standing water form, if trees fall over, so what? Introducing beavers would do the job even better than machines and likely at much lower cost. Ironically, resistance to this will mostly come from conservationists.

There has been progress in recent years. There is broad acknowledgment of what needs to be done but work is required on the social acceptance of these measures and developing the support structures, including financial. When we finally do get going, we’ll regret we didn’t start sooner.

About the Author: Pádraic Fogarty is author of ‘Whittled Away – Ireland’s Vanishing Nature’ (Collins, 2017) and is former Campaign Officer for the Irish Wildlife Trust.