First published: 17 February 2026

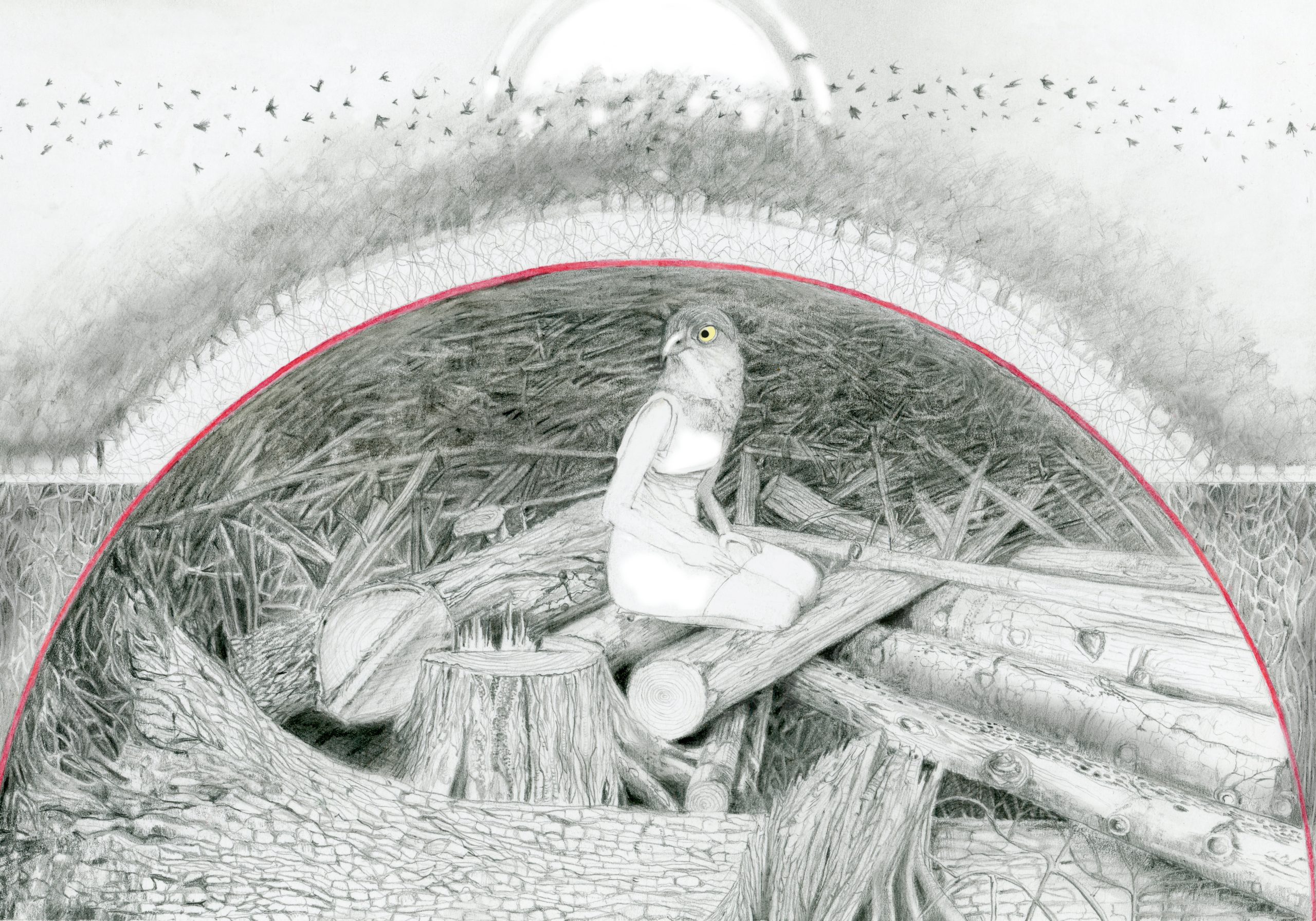

After the fox hunt, by Enagh Farrell (2025/2026). Watercolour and pencil.

A growing body of scientific studies show that we benefit physically, mentally, and socially from nature connection. Unfortunately, a recent analysis of 61 countries found Ireland to be one of the least nature-connected nations in the world. We must restore not only habitats, but also our relationship with the land and sea.

A powerful way to build communities for nature is through nature writing. At the end of 2025, we invited IWT members to submit their reflections under the theme “Nature Connection” in a short-essay format. We received a wonderful response with a range of interpretations on the theme. The judges enjoyed reading each one and would like to thank every one of our members who submitted a piece. Here follow our top three picks, along with illustrations by Enagh Farrell.

At 8pm, a special sense of calm descends upon the hide. Deep in the marsh, where the forest meets the sea, all is quiet, save for the faint rustle of birch and alder branches in the breeze.

As dusk gives way to moonless night, the marsh starts to stir. A flash of red passes through the reeds, and a water rail peers out.

“The coast is clear,” he squeals.

Two moorhen, followed by a coot, waddle across the wet mud, making their way to the hide. Little egrets follow suit, followed by grey herons. Then, songbirds. Long-tailed tits perch on the boardwalk’s edge, waiting for the raven to appear.

“Evening,” he croaks. Unpicking the latch with ease, he nudges the door open with a flick of the beak. The birds enter and proceedings can begin.

“No two ways about it. Too many humans,” grumbles the grey heron.

“Aye. Our usual patch is empty this year. No voles to be had. Another hungry month… How am I to feed my young’ins?” cries the marsh harrier.

The kestrels clamour in assent. The greenfinches start to screech, declaring “too many huuumans” with aplomb, and, soon, the water rails join in, in deafening unison.

“Order! ORDER!” bellows the bittern.

“Shhhhh! Everyone! Who goes there?” hoots the barn owl, as he slowly turns his head to face the hide door.

Suddenly everyone goes quiet. A red paw gingerly opens the door and two yellow eyes stare inside. It is a fox, followed by two badgers, a red squirrel, and a hare.

Fluttering gasps fill the air.

“What are you doing here?” asks the grey heron. “This meeting is for birds only.”

The little egrets start to jitter nervously towards the back of the hide, as the rest of the birds stare warily at the new arrivals.

“Let’s hear what they have to say,” croaks the jay.

All eyes are on the hare, who has stepped forward.

“My friends,” he says, “we may be different, but we are all united by a common purpose – to live in harmony.

“I bring you tidings of hope: we believe humans are finally seeing the light. I come from the north, where new nature reserves are allowing us to move freely. And to the south, our red squirrel comrades tell me that more forests and hedgerows are providing food and shelter.”

“Rewilding is bringing life back to the lands we once roamed. Insects are multiplying, local streams are filling with minnow, and many soils are full of worms.”

The red squirrel smiles and nods. The long-tailed tits start to chatter excitedly.

The kingfisher flies forward with a flash of blue.

“Thank you, dear hare” she says. “It will take time, but, with our help, humans can recover too. Actually, I have a suggestion, non-avian friends: will you join our future meetings? In time, we can invite a human representative too.”

“Now, that is a vision of hope,” croaks the jay.

With a timeless magic, the dewdrop turns the bog alive.

Particles of water, delicately taking shape on a spider web, weaved by ancestral skills. The arachnid approaches, trembling on her frail palace. She drinks and returns to her long wait. As the horizon cloaks itself in a gold-laced cape, the birds awake and the heather shimmers, in an explosion of noise and glitters. The cuckoo, the lark, the stonechat, the curlew. The plover, the warbler. And the most magnificent of all, the hen harrier. A tear drops down my cheek, fusing with the dew, as she rises over the marsh. She prepares for her hunt, eyes of gorse, feathers of heath. Her glide is impeccable, an ephemeral beauty, a reminder of hope for my heavy heart. She dances with her partner for a minute, or a century, agile, acrobatic, astonishing.

Midday comes and with it a new splendour. The zenith sun melts the bog into a glary dream. Perfumes elevate – myrtle, sphagnum, bedstraw. I gaze afar for a while. A graceful hare suddenly materialises himself, wise elegant silhouette of bronze, only two large ears breaking the line of the land. A crack. A twitch. A bolt. Gone forever. The place grows quieter, as if taking an afternoon nap. I lift my head and look up. Imperceptible winds move thin clouds north, outside of view. Tiny passerines crisscross the blue sky at irregular intervals, from invisible perch to invisible perch. Nothing interrupts the silent torpor, except perhaps the buzzing of bees in the nearby woodland, foraging nectar off the willow catkins.

The afternoon stretches, slowly turning into evening. The ground feels colder, and with it I. The dusk chorus eventually starts, gentle, soft, grateful, thanking the day that’s been rather than welcoming it in fanfare. I have always preferred that time of day, when the wind falls, the scents linger and the eyesight looks for familiar shapes in the increasing darkness. The full moon rises as the last lights fade. It shines its gloomy rays on the bog, reflecting on every pond, puddle and droplet. A ghostly shadow hovers the land, talons out, all ears for who may lay under the dry heather branches. I cannot hear a single rustle of its pale cotton wings. Glimpses of swooping bats soon become the only thing I can distinguish against the stellar deep blue. A snipe drums in the distance. Then all is hushed, a peaceful, late-night perfection.

[The dogs’ bites had cut deep in my side and leg. My matted red fur is encrusted with dry blood. Streams of the scarlet liquid, now a dark cobalt under the moonlight, had flowed to a nearby bog pool. As the dewdrop begins to form on my shivering coat, I lay my head on my paws, finally at rest.]

My Dad is not a very ecological man, but he loves wildlife of all kinds, even if he can’t remember the names. One of his daily joys is to feed the birds, or any visitor to the garden: foxes or stray children. When I was 8 or 9, feeding the birds was added to my list of morning jobs, it was only then I started to note the birds that appeared each day on their own schedule to fill up – and so began my first nature ritual. Slowly the number of birds and feeders grew, then they had to be refilled after lunch. My parents had a fight about the cost of bird food, but as it was “less than the cinema” it could go on. So Dad continued to share with me his ways of caring for nature: buying dog food for a hedgehog and building it a little log pile. Planting nettles in the corner for butterflies. Leaving out dead mice for the kestrels.

A few years later, a pheasant appeared by the feeders, pecking over the leftovers on the ground. The next day a special pile was left for this wild gent. From there the ritual evolved, the pheasant would sit on the ditch and call, Dad would hurry out with a handful of seed to deposit before retreating to watch ‘his friend’. Some weeks into this dance of call and feed. The call went out, the food was deposited, but looking out the window, it was not just Mr. Pheasant in the garden. There perched elegantly on the swing set were 3 fledglings and the father strutting around as if to say “look what you helped rear”. They continued to visit sporadically, before disappearing as most wild animals do. Dad kept the gap in the hedge clear, should they return.

Sometimes the rituals were less happy; when we were driving down a road and a sparrowhawk darted out of the hedge, hitting the car. We stopped, Dad found it lifeless, he tenderly placed it in the ditch. “Didn’t see it coming” and that was it, till Sunday when an extra candle was lit at mass. A year on, in spring, a pond was constructed. At first only birds came. Then a nebula of frogspawn bobbed to the surface. Their progress was monitored and a ramp for safe exit created. As they hopped about perhaps the strangest of Dad’s nature rituals was born: getting my mother to walk in front of the lawn mower brushing the grass with a stick to frighten the froglets away. Now I still have the morning job of feeding the birds. I build the log piles. I notice the fledglings in the spring. For sure there are lots of ways to connect with nature; you can count and list, travel to see rarities. It can be as simple as making your own little caring rituals and nature will slowly grow into your way of going about it all.

Homeless, by Enagh Farrell (2022). Pencil and watercolour.