Pádraic Fogarty April 22nd 2023

In the greater scheme of things, owning a dog is probably seen as at the insignificant end of the biodiversity crisis wedge. Owners of harmless-looking lapdogs or lumbering retrievers do not typically see their beloved pets as destroyers of ecosystems. I’m not a dog owner myself but I’m as fond of the mutts as anyone, even when, as once happened, a friend’s dog lunged into the long grass along our walking trail to snap at a lizard, which subsequently lost its tail.

I’ve been with friends in nature reserves where they have let their dog off the leash and have been confidently assured that their dog would quickly come to heel when called. No one likes to challenge their friends or to make a stand on an issue like this but the problems of dogs and their owners came into troubling relief recently when hill farmer Pat Dunne felt forced to close access to walkers along the popular ‘ZigZags’ trail in Glenmalure Co. Wicklow after being physically assaulted. Pat has allowed access through his land on condition that dogs are not allowed, even on a lead they can bother the sheep. With no enforcement, this has routinely been ignored (I even met a couple on this route once that had lost their dog after it bounded off after something in the bracken) so who’d blame Pat for having enough?

Dogs are increasingly recognised as a problem or, perhaps as a dog-owner would be quick to point out, the problem is irresponsible dog ownership. But not all problems are associated with their behaviour.

Some estimates suggest that a dog has a similar ecological footprint to an SUV, principally because of their meat-rich diet. And what goes in must come out, much of it coming out in outdoor spaces, including nature reserves. The estimated nearly half a million dogs in Ireland produce thousands of tonnes of faeces and urine every year, much of which enters the environment with no treatment.

One recent study from Belgium estimated that the volume of dog foul in some areas, measured in the deposition of nitrogen and phosphorous, can reach levels that would be illegal on a farm. Where this is occurring in nature reserves, it may be affecting the local ecology through excessive artificial fertilisation, reducing the biodiversity of plants in particular. Many dog owners see no harm in this and while most are no doubt responsible and bring poo bags, these are then sometimes hung on branches. Nothing is done about nitrogen-rich urine.

And these effects are seen when dogs are kept on leads. When they’re off the lead we see a whole different level of negative impacts. One 2020 study found that insecticidal flea treatments, which include substances which have been banned on farmland, are washing into rivers. In the UK it is estimated that 80% of dogs are receiving flea treatments and this study found that 99% of samples from 20 rivers contained levels of finopril, with concentrations of one breakdown product on average 38 times the safety limit. Author of the 2021 book ‘Silent Earth’ and entomologist Prof. Dave Goulson told the Guardian newspaper that “the problem is these chemicals are so potent… one flea treatment of a medium-sized dog with imidacloprid contains enough pesticide to kill 60 million bees”. These poisons can enter the environment by washing dogs at home but allowing dogs to jump into rivers and lakes is also a source.

And then there’s the disturbance. Many popular places for people to walk, with or without their dogs, also happen to be nature reserves (partly as a result of very restricted access to the Irish countryside). People see little harm in letting their dog off the leash in the local forest or coastal beach to get a bit of exercise, but where’s there’s one dog, there’s typically another one not far behind. For birds in particular, whether they’re trying to nest in the spring and summer, or fatten up over the winter in preparation for migration, this continual harassment can be devasting for whole populations.

In Dublin, the country’s most populous region, Sandymount Strand and the area around Bull Island at low tide are filled with people, dogs, horses, you name it. Dublin Bay, Malahide Estuary and Baldoyle Bay are all ‘Special Protection Areas’ for coastal birds but studies which are now a decade old found that disturbance by dogs in each of these areas was ‘high’ or ‘moderate’, and in some cases more or less ‘continual’ (along with other unregulated activities like jet-skiing and digging for bait or shellfish).

You might well wonder how these places retain any ornithological interest at all in the face of this pressure. But the fact that you might see impressive numbers of birds while out and about in these areas is masking serious declines of wintering waterbirds in Ireland. A 2018 study by BirdWatch Ireland recorded a decline of 138,160 birds (15%) between the four winters from 2011-2016 compared to the previous 2006-2011 period. This is a very short interval to see such a dramatic fall off in numbers. Some species of duck, such as shoveler, pochard and common scoter saw declines of over 30%. The study found climate change to be an important driver but noted that “this should not mask the many local pressures faced by wintering waterbirds”, which include recreational disturbance.

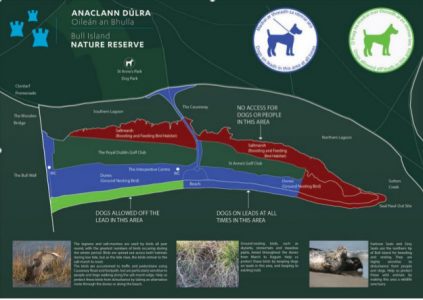

Zoning of Bull Island

And it’s not just birds. Bull Island, north of Dublin Bay, is believed to have lost its population of Irish hare due to harassment by dogs.

A response has been long in coming. Dublin’s Bull Island enjoys every kind of protection that exists, from National Nature Reserve to UNESCO Biosphere Reserve but like all the other ‘protected’ areas, these designations have brought little noticeable change to site management. Disturbance from dogs was identified as an issue in a Management Plan for the island in 2009, indeed by-laws prohibiting dogs off-leash are in place since 1994, but have never been enforced. The rusty signs can still be seen.

An updated ‘Action Plan’ was published in 2020 and which proposed a zoning of the island to keep people and dogs away from the salt-marsh (vital feeding grounds for the birds) and the north of the island (where seals can haul out and would give birth if they were given a bit of peace). Walkers on the dunes will be required to keep dogs on a leash at all times. Last month, a press statement from Dublin City Council said this would come into being at the end of April. But it also said that this would be based upon a ‘voluntary code’. In other words, there will be no enforcement of these rules.

Why are rules for the protection of wildlife not enforceable in the way that parking violations or littering are? All of our important wildlife sites need information boards, wardens and a programme of education to explain to people why they are important and worth protecting (not to mention actual management measures, something Ireland is being taken to Court for by the EU). But it is senseless to think that without rules that can be backed up with fines there will be any lasting impact.

So maybe the problem isn’t dogs, it’s not even irresponsible dog-owners, it is the reluctance of the State (which includes local authorities and the National Parks and Wildlife Service) to take responsibility, something described in the recent report of the Citizens’ Assembly as a ‘fundamental disappointment’.