This year, marine policy has been at forefront of the Irish Wildlife Trust’s advocacy efforts, as we collaborated with multiple NGOs to lobby for enhanced marine protection. Read the following sections for an in-depth look at some of the highs and lows of marine conservation in 2023.

In January, pre-legislative scrutiny was undertaken by the Joint Oireachtas Committee on the new Marine Protected Areas Bill. The Irish Wildlife Trust, along with colleagues from Fair Seas, Birdwatch Ireland and the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group, submitted written and aural evidence and recommendations during this process. We were happy to see that all of our recommendations were taken on board by the JOC in their report.

Our partners Fair Seas held 2 events in the AV room in the Dáil this year addressing politicians and highlighting the importance of this bill.

We presented nearly 12,000 signatures (collected in only 4 weeks) to the government calling for the implementation of new MPA legislation.

Fair Seas also held a World Ocean Day Conference, with global experts and national stakeholders joining together to discuss the need for MPAs in Irish waters and learning from best practice in MPA management around the world. Several important documents were published throughout the year including a sustainable financing report documenting how much it would cost to designate and protect 30% of Irish seas by 2030. Unfortunately despite there being promises made by the government that we would have this bill before the end of 2023, we have now been told that it will be next year before it is released.

There is no time to waste in protecting our waters and we hope that this bill is progressed without delay and doesn’t fall alongside the current government

A new protected area was designated in July of this year, The North West Irish Sea SPA. While it is always good to see new designations, without site specific management plans in place and enough resources allocated to effectively enact these management plans, these designations are little more than paper parks. One of Fair Seas key asks for the new bill is to ensure effective management of our marine protected areas.

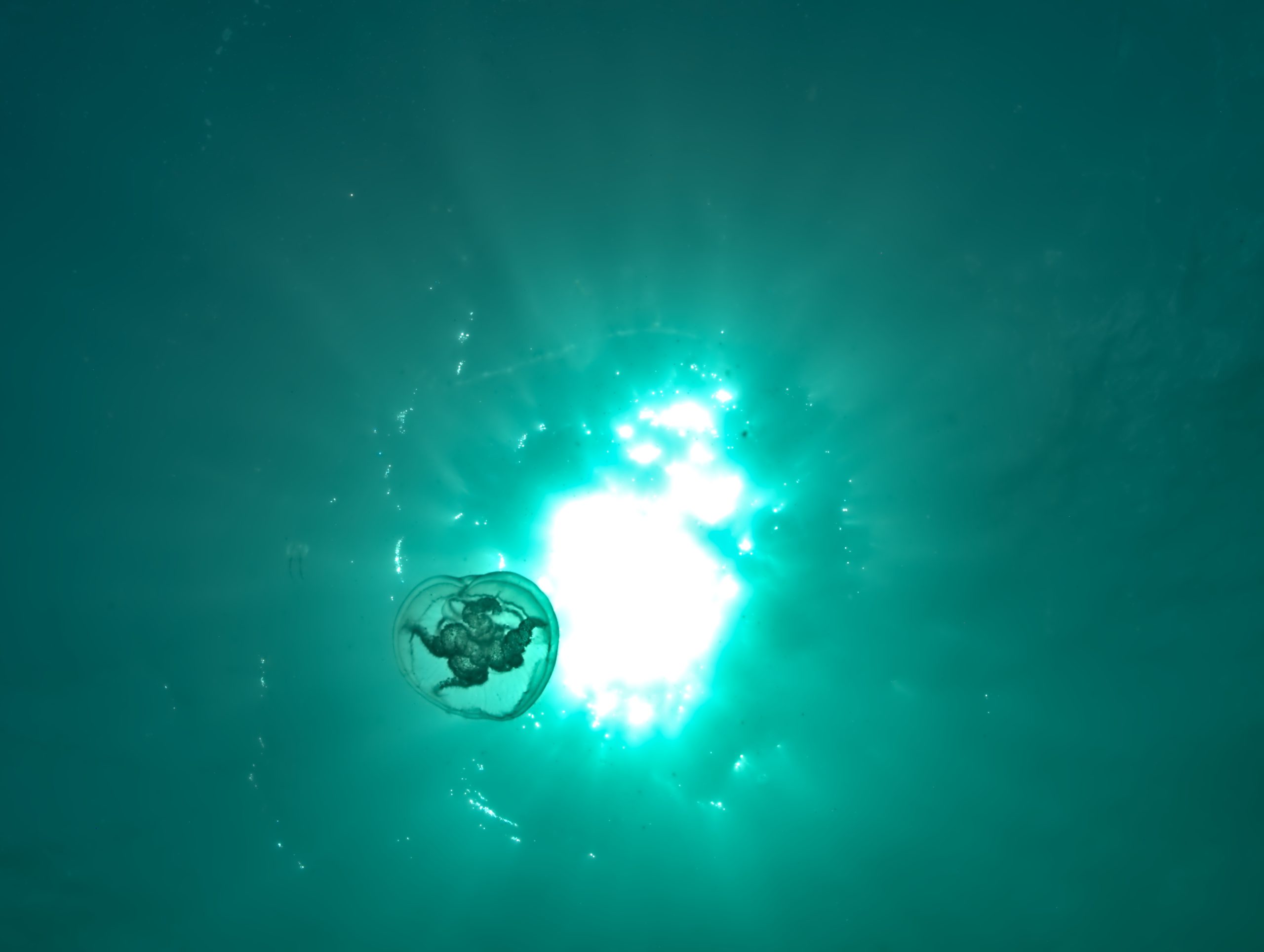

Image courtesy of Fair Seas

Two new revelations by government early this year ensured that we took several steps backwards in protecting our marine environment. A quota for the IUCN listed vulnerable spurdog was announced for 2023. This fishery has been closed since 2011 and spurdog is also listed as a prohibited species in the EU (which means we have no real data on numbers of bycatch for this species). Reopening this fishery could mean disaster for their numbers as they tend to shoal together and entire groups of pregnant females could be taken from the water in one go.

Image courtesy of Mark Conlin

In a devastating turn of events the trawling ban on vessels over 18m within the 6 nautical miles around the coast was overturned in March this year. The ban, which was originally brought into force in January 2020, was supported by not only environmentalists but also fishermen and anglers. Trawling has wide ranging negative impacts on the marine environment and pair trawling for small forage fish such as sprat in inshore waters has a knock on effect for the entire marine food web. In better news, Northern Ireland enacted management measures to prohibit bottom trawling in 9 of their inshore Marine Protected Areas which shows a stark contrast to the protection of the inshore waters in the Republic. On December 14th, Minister McConalogue announced plans to initiate a new public consultation regarding the reinstatement of the trawling ban in inshore waters. This will follow the collection of current scientific and economic data. It’s important to note that the reversal of the ban was not a reflection of its ineffectiveness in safeguarding the inshore marine environment, but rather due to legal technicalities. There is no time to waste in reinstating this ban.

The EU released their Action Plan for Protecting and Restoring Marine Ecosystems for Sustainable and Resilient Fisheries. This Action Plan has asked Member States to put together a roadmap by March 2024 on how they can move away from destructive fishing practices such as bottom trawling and ensure a just transition for all.

Five years after initial discussions began to reform the EU Fisheries Control Regulation, trilogues came to a close. There were many wins for marine conservation, notably, the requirement for vessels to maintain electronic logbooks to enhance the accuracy and transparency of fish traceability. Additionally, the installation of CCTV on high-risk vessels aims to curb quota violations and bycatch issues, while real-time tracking systems on all vessels will show locations in real time. However, a concerning change has been the shift to applying the margin of tolerance for tropical tuna to the entire catch, rather than on a per-species basis. This will need to be increased investigations and heightened enforcement at ports to prevent potential misuse and underreporting for higher-value, vulnerable tuna species. Protected areas alone are insufficient; it is crucial that fishery conservation measures are strictly enforced.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s 2022 report on Ireland’s water quality revealed a continued lack of improvement following a decade of decline.

Agriculture and wastewater treatment are the main causes of nutrient pollution with intensive agriculture releasing high levels of nitrogen into water bodies.

Presently, legal proceedings are underway concerning the Nitrates Action Programme, due to the fact that the independent environmental assessment acknowledged an uncertainty as to whether the main measures relied upon to prevent water pollution would sufficiently work. There was a revision to the nitrates derogation under the EU Nitrates Directive. This caused outrage among farming organisations even though clear links between intensive agriculture and environmental decline have been shown and Ireland has consistently failed to meet EU water quality targets. Farmers need to be incentivised and rewarded for making changes to more sustainable environmentally friendly practices otherwise there will continue to be clashes.

The new programme of measures (PoM) was announced for the Marine Strategy Framework Directive where Ireland failed to achieve good environmental status for 6 of the 11 indicators. There were 12 new measures added to the PoM, 4 measures which existed but were not mentioned in the last report and 28 measures modified to attempt to rectify where we have failed to hit our conservation targets.

A treaty to protect Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) for the high seas was signed this year. This treaty will allow for the establishment of large scale MPAs in areas which up until now had no real management of activities occurring there. There will also be environmental impact assessments conducted and measures put in place for illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. This new global agreement will help deliver on marine conservation for the global ocean.

There have been many ups and downs this year and it is disappointing that we still don’t have the much needed MPA legislation. With a promise that this will be released in the first quarter of 2024, we have high hopes that with persistence and continued public pressure, 2024 will be a good year for marine conservation.