Pádraic Fogarty 1st July 2023

The Government recently celebrated three years in office, how is it doing in meeting nature objectives? I wrote a blog after its first anniversary in 2021 and the same terms and conditions apply to the one you are about to read. A year is not a lot of time to judge a government’s performance. After three years we should expect some clear signs of achievement, while the two years left to run provide only a small window for new initiatives. The headings I am using below are the same as for my 2021 blog to allow for some consistency in my praise and criticisms and these are in the same order as they appear in the Programme for Government (PfG).

“Progress the establishment of a Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity”

The Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity Loss published its final report in April with 159 recommendations. It’s a thorough piece of work and we were happy that it supported many of the policy positions long-promoted by the IWT and others in the environmental NGO community. This week it was decided that the report will go to the Joint Oireachtas Committee on the Environment and Climate Action chaired by Brian Leddin. This committee published its own report on biodiversity only last November and there is a lot of commonality between the two. Clearly, we have enough reports and what we now need is a programme of prioritisation and implementation. For greater legitimacy however we do hope that other committees will get involved in this work, particularly the Committee on Agriculture, Food and the Marine.

“Review the remit, status and funding of the NPWS”

I think we can report good progress in this vitally important task. We had always said that without a functioning nature conservation agency to spearhead implementation of laws and regulations then nothing else would fall into place. We are happy that Minister of State Malcom Noonan has secured additional funding and a progress report for year one of the three-year plan maintains that things are broadly on track. The NPWS is now a statutory agency with former-assistant secretary at the Department of Housing Niall Ó Donnchú now director general of the NPWS.

Structural changes of this scale (changes to IT systems, recruitment etc.) are never easy but if done properly will provide resilience. While this is clearly progress, I can’t understand for the life of me why the communications and presentation of the NPWS and its work remains so dreadful. I had hoped that the agency would be given a new name, logo and identity but instead we have the same exhausted looking website, still no social media presence of note and no presence on mainstream media, e.g. a person doing interviews with radio and press. When you add the fact that actual conservation activities on the ground have yet to appear even in high profile places like Killarney National Park, it is easy for people to conclude that nothing is happening at all. This is an unforgivable own goal given that there are good stories to be told and easy things which could be done.

“Seek reforms to the CAP [Common Agricultural Policy] to reward farmers for sequestering carbon, restoring biodiversity, improving water and air quality, producing clean energy, and developing schemes that support results-based outcomes.”

The new CAP came into being in 2023. It will deliver nearly €10 billion to Irish farmers over its lifetime (to 2027) however, only 15% of this will be directed to results-based measures that incentivise tailored schemes rather than the general ‘bird box’ approach that has dominated so far. The Environmental Pillar dismissed Ireland’s CAP Strategic Plan as “failing the environment”. If we had measures in place to reward farmers for sequestering carbon would we have seen the outrage over the Nature Restoration Law? Unlikely.

Meanwhile, ammonia and greenhouse gas emissions from the sector both increased in 2021 while nutrient loadings in the south and east, mostly from dairy farming, are also leading to deterioration of water quality. At the end of the day, there are no effective controls on pollution from agriculture.

On the plus side, the hated rules around ‘eligibility’, which perversely incentivised farmers to remove scrub and wetlands, are gone. A farmer may now have 50% of a land parcel in ‘beneficial features’ (e.g. scrub and wetlands) with no penalty while, very significantly, 100% of land can be eligible if helping to meet a climate, biodiversity or water quality aim. This message may not have quite seeped through to those trying to manage land for nature but it has enormous potential to deliver results.

Agriculture remains the boil that needs lancing. A major problem is the continued greenwashing by Bord Bia or Minister Agriculture for Charlie McConalogue who continue to assert that Ireland’s food system is ‘sustainable’ or that farmers are “farming with nature”. This mixed messaging is a major block to getting on with the transformation that’s needed in agriculture.

“The government will undertake a national land use review”

Phase 1 of the Land Use Review was published in March. It makes for interesting reading but how it will be applied remains to be seen. A hint at where it might be going was revealed in a report commissioned by the Environmental Protection Agency looking at how land use needs to change to meet net-zero emissions targets by 2050. Its conclusions, that forest area needs to double, livestock numbers need to come down by 30% in addition to a 30% emissions reduction in the herd that remains and rewetting nearly all our peatlands, were treated with accusations of “ethnic cleansing” from TD Michael Fitzmaurice.

“Publish a successor forestry programme to deliver an ambitious afforestation plan”

A lot of work has gone into forestry by Minister Pippa Hackett and the ‘Project Woodland’ forum (IWT was a member). An exhaustive review of the regulations confirmed that environmental regulations must be followed and will not be weakened. Minister Hackett also approved a substantial €1.3 billion for the next Forestry Programme. These are both positives.

However, the longed-for transformation of forestry into a nature-friendly model did not appear, much to my dismay. While the Forest Strategy has not yet been approved by the European Commission (perhaps because of their concerns over planting industrial monocultures on peatlands or the loss of valuable sites for ground-nesting birds) the most recent draft envisages only marginal increases in native woodland or even continuous-cover forestry, with the bulk going to yet more blocks of monocultures destined to be clear-felled. Given the past and even recent statements from Ministers Hackett and her colleague, Minister for the Environment Eamon Ryan, about ‘the right trees in the right place’, the failure to deliver more than slogans for forestry is a major disappointment and a black mark on this government’s record to-date.

“Extend the badger vaccination programme nationwide and end badger culling as soon as possible”

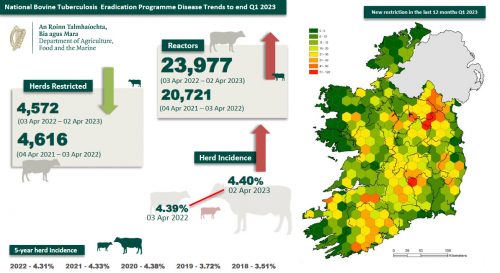

In 2020, the year the government took office, 4,723 badgers were snared and shot by the Department of Agriculture. In 2021 the figure was 5,868. So, the opposite of ending culling. Meanwhile, TB rates in cattle are increasing, something that the Department itself has said is associated with dairy expansion. This is another serious fail (not only for badgers) on the Government’s side.

TB rates in cattle going up

“We are fully committed to the environmental objectives of the Common Fisheries Policy” (CFP)

The matter of overfishing has now gone to the European Court of Justice, which is due to issue a ruling on the legality of exceeding scientific advice this autumn. It is expected to uphold the finding of the Irish High Court that setting quotas beyond scientific advice is illegal. Rather than being committed to environmental objectives of the CFP, the Irish government tried to defend overfishing in the High Court. If we do, finally, break out of the pattern of ignoring scientific advice, it will be no thanks to the Government.

In another fail, the High Court over-ruled the Government’s restrictions on trawling in inshore waters, meaning that five years of effort to protect this vulnerable zone have been wasted. We are no nearer ensuring “that inshore waters continue to be protected for smaller fishing vessels and recreational fishers and that pair trawling will be prohibited inside the six-mile limit”, as promised in the PfG.

In better news, there does seem to be greater assertiveness and capability on behalf of the Sea Fisheries Protection Authority to enforce fishing regulations while new rules that will mandate tracking all boats and CCTV on high risk boats were recently passed, with Government support, by the EU.

“We will realise our outstanding target of 10% under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive as soon as is practical and aim for 30% of marine protected areas [MPAs] by 2030.”

MPA coverage has increased to over 8% from a pitifully low 2% last year and are set to increase further, perhaps to the promised 10% threshold by the end of the year. Good news.

However, designations do not bring protection and actual management measures for the MPAs we have are still woefully poor. New legislation to drastically expand the MPA network to at least 30% by 2030 has been drafted and we are waiting to see an update in advance of Dáil amendments. The initial draft was quite poor but will hopefully be improved following a good report from the Oireachtas committee that looked at it.

An emerging issue we are seeing however is a reluctance to create ‘strictly protected areas’ (effectively no-fishing zones). The Irish government (Minister McConalogue again) is resisting a ban on bottom trawling in MPAs while even Malcolm Noonan’s department is resisting setting restrictions on bottom trawling in an effort to protect a fairly modest 10% of seabed.

I write this blog just after the European Court of Justice issued a final ruling against Ireland for failure to implement the Habitats Directive. Malcolm Noonan responded by saying that Ireland was “making good progress” in addressing the ruling and while that might be true within his particular (corner of a) department, it can’t be said for the wider land and sea use sectors that are driving the biodiversity crisis – especially agriculture and fishing but also forestry and peat extraction.

The government did, finally, come out strongly in favour of the EU’s Nature Restoration Law including, to his credit, Minister McConalogue. The idea of a dedicated Nature Restoration Fund to finance measures and deliver money to farmers and fishers will be a litmus test for how deep that support runs. This would certainly help to tip the dominant narrative that nature restoration is an attack on farming and ‘rural Ireland’. But without transformation of the key sectors the Government will fail to reach its environmental objectives. And there’s no sign of that happening.