“On the chilly lakelet, in that pleasant gloaming,

See the sad swans sailing: they shall have no rest:

Never a voice to greet them save the bittern’s booming

Where the ghostly swallows sway against the West”

“We can truly feel the very spirit of the wild has been restored if the booming call of the bittern echoes across the marshes once more”

Artwork by: Naomi McBride

In the ancient legend of the Children of Lir, the eponymous siblings – Fionnuala, Aodh and the twins Conn and Fiachra, are transformed by Lir’s jealous second wife into swans.

In this form they would stay for nearly a thousand years “sick with human longings, starved of human ties, with their hearts all human cramped to a bird’s stature. And the human weeping in the bird’s soft eyes” in the words of poet Katharine Tynan.

Legend has it that the spell would be broken after 900 years but, as Tynan’s closing stanza puts it:

“Housed warm are all things as the night grows colder,

Water-fowl and sky-fowl dreamless in the nest;

But the swans go drifting, drooping wing and shoulder

Cleaving the still water where the fishes rest”[i]

The swans, thankfully, are still with us.

When I was a child I learned that Ireland had three species of swan: the Mute Swan, the Bewick’s Swan and the Whooper Swan. But these days we really only have two.

The Mute Swan is probably the most familiar of the three, resident year-round, staying by their mate for life and, unless hissing at a passing dog, mute.

The Bewick’s Swan, meanwhile, is a winter visitor. Or, at least, it was; the numbers in Ireland have dropped like a stone in the last 30 years and are now only turning up at 1% of their numbers compared to the 1970s.

This is thought to be due to climate change, with the swans ‘short-stopping’ in other countries between Ireland and their Arctic breeding grounds, but their overall population is also in decline.

The Whooper Swan, finally, is another winter visitor and in appearance very similar to the Bewick’s Swan. In contrast to their cousin, however, there has been a 40% increase in the number of Whooper Swans wintering in Ireland since the mid-1990s.

They gather in flocks on lakes, river floodplains and sheltered coastal waters pretty much all over Ireland. They’re a joy to watch… and to hear! On a still winter’s day along the slowly drifting Shannon River somewhere in the midlands, their communal honking rings out across the farmland. From a distance they could even be squabbling siblings.

For many, swans are the epitome of grace and elegance, but on this January day in 2020 I am looking on a small flock of Whooper Swans which are anything but.

On water they glide effortlessly, in the air their long, slow wing beats are assured, but on dry land they have all the poise of a fully-suited scuba diver in a conference centre. They honk as they waddle, lifting their broad, webbed feet clear of the grass before pushing on awkwardly in their small delegation.

They feed on the pasture during the day but in the evening they take flight, returning to a nearby lake or expanse of open water where they can rest, free from the threat of land-based predators. In this corner of County Longford, that normally means Lough Ree along the River Shannon, or perhaps, if conditions allow, flooded winter fields.

Whooper Swans. Image source: Mike Brown

Back in the day, the vast raised bogs that clung to the banks of the Shannon were good enough for the swans but the bogs are now largely gone. They were replaced with machinery, railway lines and workers.

The smokestacks and barrel-shaped cooling towers at Lanesborough and Shannonbridge rose from the flat plains as monuments to this industry. These peat-fired electricity stations powered the nation in economic hard times and employed thousands of people for decades.

“Bord na Móna [the state agency established in the 1950s to exploit the bogs] have been a major positive for this area” says Niall Dennigan, a native of Magheraveen, a townland not far from the power station at Lanesborough.

“My father worked for Bord Na Móna for the best part of 11 years… uncles as well, the company has been the heart and soul of this area. Most people around here are gutted that the power station is closing down”.

In November 2019, the ESB (the principle energy provider in Ireland and operator of the peat-burning power plants) announced that the two facilities at Lanesborough and Shannonbridge (West Offaly) would cease to operate at the end of 2020. With their closure, 80 ESB jobs and over 100 Bord na Móna jobs are to be lost. At their height the two power stations employed over 170 people, while hundreds more have been employed indirectly.

The imminent death of industrial peat extraction should be a surprise to no one.

Since the first machines cut into the spongy surface in the 1950s the end has been in sight. Individual bogs first became worked out in the early 1980s, spurring the Royal Dublin Society (RDS) to hold a seminar on the matter, noting then that “the most memorable feature of that first day must be the series of utterly fundamental questions on the regional social and economic implications of the inevitable changes… references were made to “whole villages for sale”. “Devastation” was a term used more than once.[ii]“

In October 2015 Bord na Móna announced that it would formally cease all industrial peat extraction by 2030. This decision was criticised at the time as being too far out, it was already clear that the company’s intensive use of state subsidies and unsustainable carbon footprint would not allow it limp on for another 15 years.

At the 1988 seminar a series of men (and they were all men) were invited to the RDS to ponder the future uses of the midlands bogs. Much of the land, it was assumed, would be suitable for plantation forestry. Investigations into converting it into productive grassland – arguably an endeavour which has been under way since the dawn of agriculture in Ireland – were under way but were thus far unpromising.

The Managing Director of Bord na Móna at the time, Edward O’Connor, was nevertheless upbeat, noting that peat exploitation globally was “nowhere near maturity”. Exciting developments were under way in Russia and Finland, while in the arid province of Almeria in Spain “success is to be anticipated” in growing fruit and vegetables on a peat medium where irrigation was dependent on over-exploited, salty groundwater.

There would be exciting commercial opportunities in the “cleansing of liquid and gaseous effluents” as well as undefined “medicinal and therapeutic effects”. Ireland’s groundwater pollution problem would be “cured” using peat to filter wastewater from dodgy septic tanks while peat could “scrub noxious odours that emerge from meat rendering plants, fish processing plants and any other organic based noxious gas emitter”.

Furthermore, there would be a “niche market” for peat (“properly marketed, priced and packaged”) as an absorbent for oil spills and even heavy metals – “the peat can then be incinerated in a controlled way to recover the metal”[iii].

Mr O’Connor concluded his delivery by saying that “we have to develop a brand of entrepreneur who will not rest until he has set up new businesses and is trail blazing Irish peat at profit across the world stages.”

Few of these wheezes came to fruition. Peat in septic tanks gained some traction. Commercial forestry, by far the largest of the enterprises in terms of the anticipated land area to be employed, quickly proved to be unviable.

But Bord na Móna’s determination to blaze the commercial trail did not cease.

By 2015, then-Chief Executive Mike Quinn was announcing the cessation of peat extraction but the company was set to transform itself into an alternative energy company, centred on biomass, wind and solar power. According to the Irish Times, the traditional peat briquette was to be transmogrified into ‘biomass briquettes’ while the semi-state company would be opening a new wind farm every year for the next seven years, many of which would be in conjunction with solar panels. Biomass, he said, was a “huge opportunity”.

Yet, things didn’t quite work out. The biomass which was burned in the power plants included palm kernels sourced from palm oil plantations (i.e. former rainforest) in Indonesia as well as biodiverse forests in the USA and they were even importing wood product from as far away as Australia. Hardly in keeping with its new ‘naturally driven’ slogan.

The burning of palm kernels came to a halt in 2017 while plans to invest €60 million in a wood pellet plant in the US state of Georgia were dropped following protests from local environmental groups.

Grants to encourage farmers in Ireland to grow miscanthus, or elephant grass, were a flop because burning the plant produced chlorine which corroded the boilers. Farmers were subsequently wary of later schemes asking them to grow willow.

In early 2018 the then-Minister for Climate Action Denis Naughten heralded the announcement to convert peat-burning power plants in the midlands to biomass as “historic”.

But it was the failure of the company to source biomass that led to the announcement a year and a half later that power plants at Lanesborough and Shannonbridge would be shut down permanently. Since then we hear that Bord na Móna is tapping birch trees for their sap, a popular drink in Finland apparently, and something which we’re told is part of the company’s ‘Brown to Green transformation’.

Chief Executive Tom Donnellan told the Westmeath Examiner that “where we once milled peat we are now harvesting a pure, new, entirely natural and organic health product. The Birchwater Project is still in its development phase but is progressing well with excellent harvest yields from these peatlands”.

There’s also talk of fish farming and herb cultivation, something which its website says is “inspired by the unique nature and beauty of our peatlands”. The company has a number of wind farms up and running, but new developments are not appearing at the pace which was anticipated.

No solar energy farms had been approved at the time of writing while during the summer of 2020 all industrial peat extraction was forced to cease arising from a protracted legal battle with Friends of the Irish Environment due to the lack of environmental impact assessment for any of Bord naMóna’s operations.

Bord na Móna was established as a semi-state company and it is in their DNA to ‘blaze a trail’ for profitable exploitation for the bogs. In a way their relentless pursuit of a commercial ‘use’ for the bogs is a broader reflection of the Irish psyche which expects land to be under active cultivation.

For centuries the bogs were seen as wasteland, a quagmire, an impediment to our progress as a nation and then, when the means became available, a resource to be exploited. I don’t blame Bord na Móna for their heroic struggle for commercial innovation. I’m certainly not against renewable energy developments, particularly wind and solar, which are essential for decarbonising the economy.

I just wish the company could be put out of its misery so that we can talk about where the real potential for the bogs lies: nature restoration.

Back in Magheraveen Niall Dennigan is getting his coat. It’s a glorious winter day and he’s keen to show me around. This is where he grew up. Although he worked for a bit as an electrician in Dublin he felt the pull of home and moved back to Longford with his wife to rear their three children. They built their own home which is near their parents’.

Niall’s story shows that the common line about rural Ireland ‘dying on its knees’ is more complicated than it seems. People like him want to live in these areas but they are not getting jobs with the traditional employers – which, in this part of Longford, has been Bord na Móna for the past 70 years.

“There’s no employment here at the minute” Niall tells me, “I can live here because I can work from home, but for that I need a good broadband connection. Lots of people around here still don’t have that”.

Five years ago, the low hill to the west became the site of a wind farm, a project run by the state forest agency, Coillte. Niall insists that he is not against wind farms but believes that the project did not take local concerns into account.

“It was a one-way street with them. There was no meaningful consultation with people, the community was just presented with the plans”, he says. It soured local opinion. “For years people had put their faith in Bord na Móna, they told the community that they would keep people working. But there are very few jobs in wind farms.”

Despite knowing for decades that turf-cutting would end, at the time we spoke no plan had been put in place for workers who were then facing redundancy. Mention of a ‘just transition’, Niall says, is greeted with scepticism. “We had been promised that the bogs between here and Lough Ree would form part of the Shannon Wilderness Park, and we were very excited about that.

Bord na Móna promised that once they were finished removing peat from the bogs that it would be handed back to the community. We were excited about the tourism and amenity potential for the project”. So, when Bord na Móna applied for planning permission in early 2019 for a 24-turbine wind farm on lands at Derryadd near his home, the very lands that were promised for the Shannon Wilderness Park, Niall led local opposition.

The idea that the worked-out bogs could be given back to nature is not new. Back in 1988 at the RDS, then minister for Energy and Communications Ray Burke told the seminar that “where cutaway [bog] is low-lying and has been exploited through the use of pumps, it will generally flood once these pumps are turned off. Even if left alone, such sites quickly form scenic areas, as reeds and birch trees naturally colonise the surrounding residual peat and wildlife re-establishes itself.”

Burke, who spent four and half months in prison in 2005 after pleading guilty to making false tax returns, was suggesting the idea – something which would today be quickly recognised as ‘rewilding’ – as the last resort, after forestry, conversion to agricultural land or any other commercial use had been ruled out. Later, the idea took root in some local communities.

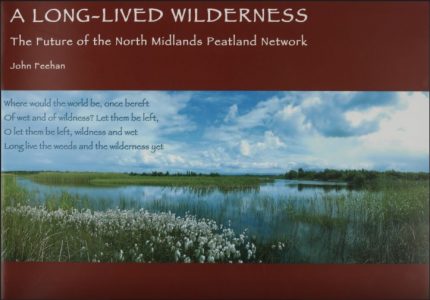

This prompted John Feehan, a figure well-known to many in the midlands and beyond for his prolific writings on the ecology, heritage and history of the region, to write a prospectus in 2004: ‘A Long-lived Wilderness: The Future of the North Midlands Peatland Network’ which set out the opportunity in developing a Wetlands Wilderness Park centred on the Bord na Móna lands in the north midlands. It would be vast, hugging the northern shores of Lough Ree and encompassing a cluster of industrial bogs referred to as the Mount Dillon group. In it he wrote:

“Once harvesting activity comes to an end – indeed, before in many cases – natural processes of recolonisation take over on the cutaway, and in time the bare surface is replaced by a mosaic of evolving ecosystems of great ecological interest that develop on the residual peat. There will be woodland and scrub, dominated by pine, birch and willow. There will be oases and fringes of natural acid grassland, fen, marsh and small areas of bog, with considerable areas of shallow open water and the marginal habitats associated with it. These spontaneously established ecosystems are in equilibrium with the changed conditions which human exploitation of the original bog has brought about.”

Nature just needs time and space

In short, very little needs to be done. “A modest amount of intervention” is sometimes needed to retain water in shallow lakes – the plan states – “but this should never be on a scale, or use materials, which are out of character with the developing wilderness. Wilderness requires that we keep our hands off and let an ecological equilibrium that is in tune with the altered conditions establish itself.”

Feehan envisaged the return of lost species such as the marsh harrier and the booming of the bittern, a bird which disappeared from Ireland in the 1840s.

In 2011 the Golden Eagle Trust (GET) invited a pair of Swedish ecologists to visit the bogs in the Mount Dillon Group to assess them for their suitability for reintroducing cranes, another long-lost bird. Lorcan O’Toole, from the GET showed them around and they concluded that there are “oodles of suitable crane habitat” available.

It is still an ambition of the organisation to bring cranes back to Ireland but when I spoke to Lorcan for this research he told me that “the Golden Eagle Trust wouldn’t have anything to do with a crane reintroduction project that was anywhere near a wind farm”.

Meanwhile, local ornithologists eye the skies for wandering white-tailed eagles in the hope that this top predator might establish a territory on the shores of Lough Ree.

In 2013, Longford County Council published their plan to realise the Mid-Shannon Wilderness Park as an amenity destination of “international value”. There’s no doubt that a vast wilderness area with a rich patchwork of native woodlands, lakes and wetlands, with great flocks of birds including bitterns, cranes and white-tailed eagles, would be attractive to tourists from home and abroad.

It would avail of existing walkways along the Royal and Grand Canals, boating and kayaking along the River Shannon through Lough Ree and heritage sites such as the Corlea Trackway, a 2,000-year-old wooden boardwalk designed to cross or, perhaps, access the centre of the bog for ritualistic purposes.

The Longford County Council document is mostly about amenity and realising the potential tourism value of the project. It also stresses that the project would be perfectly compatible with renewable energy projects. It doesn’t dwell on the word ‘wilderness’ too much, perhaps relying on its self-evident evocations.

It’s been on the shelf for too long

It was probably wise that they didn’t try to define what a wilderness is, but if anything, ‘wilderness’ is equivalent to ‘nature first’. Are commercially intrusive projects like wind turbines and solar parks compatible with wilderness?

Would people travel from abroad to visit a ‘wilderness’ that wasn’t really true to its name? Certainly, any proposal to reintroduce cranes to a landscape with wind turbines 185m in height (one and a half times the height of the spire in Dublin’s O’Connell St) would be off the table.

Although wind turbines are not the bird-killing machines portrayed by some, there are particular birds which are susceptible to fatal strikes – including large or soaring birds such as cranes, white-tailed eagles and whooper swans.

These were the arguments presented to a special hearing on Bord na Móna’s wind farm proposal, to be located bang in the centre of the proposed Shannon Wilderness Park, held in Longford in July 2019. I was there on behalf of the Irish Wildlife Trust to put forward our objection to the scheme. Niall Dennegan, and his ‘No to Derryadd’ community group presented a robust critique of the planning documents, including the likely effect the turbines would have on the local whooper swan population.

When I visit him in January 2020, a final decision had yet to be made. Niall drives me up a local road to a nearby bog where peat extraction stopped some years ago. On either side of the road a brown expanse of bare peat stretches out to the horizon. This is also the site for one of the proposed turbines.

The weather has been wet and on the north side of the road, off in the distance, large pools of water have formed. Through the binoculars, we can just about see three white shapes gliding across its surface. It is a small group of whooper swans, bowing their heads and honking to each other, deep in conversation. Around the edges we can also see the establishment of mosses, rushes and the first saplings of birch and willow recolonising the peat.

Although this process would continue even in the presence of a wind turbine, Niall tells me that Bord na Móna would be required to maintain the pumps to keep the area dry while the rotating blades would present a demonstrable hazard to the swans. “They simply won’t hang around if the wind farm is allowed to go ahead” he says.

We finish our day with a walk across Niall’s father’s farm, which borders another edge of the bog. It’s a silent landscape with no birds or even leaves to catch the whisper of the wind. But Niall tells me that last summer the silence was broken by a sound not heard in many decades – the cry of the curlew.

In the summer of 2019, it was believed that a pair of curlew, one of Ireland’s rarest and most threatened birds, had nested on a rushy corner of the cutaway bog. The sound is unmistakable. “We’ve had silence here for many years,” says Niall, “but now the sounds are coming back. If we stay true to the Wilderness Park idea we have such a positive alternative to reimagine the midlands.”

Later in 2020 it was announced by the new government that 33,000 hectares of mined out midlands bogs, less than half Bord naMóna’s landholding, would indeed be rewilded and rewetted. According to Green Party lead Eamon Ryan, the move will prevent the release of 3.2 million tonnes of carbon dioxide by 2050. The plan would keep Bord naMóna workers in a job after the power plants closed and there’s no doubt that this is the most significant step we’ve seen towards healing this damaged landscape. Also, that year the company received planning permission for their proposed wind farm at Derryadd, although this decision was subsequently sent for a judicial review, and as of March 2021 a final ruling had not been made.

Image source: Curlew by Mike Brown

Peatlands can be described as a kind of ‘super-habitat’. Across the globe, they store about a quarter of the world’s soil carbon even though they only cover 3% of the land area. What really makes them special though is their phenomenal ability to remove carbon from the air and lock it away more or less permanently (other types of soil also build up over time but much more slowly).

As well as their climate benefits, they act as giant sponges, regulating the flow of water off land and thereby moderating the peaks of flooding and the troughs of drought in river catchments.

And they clean water too. United Utilities, a water company in the north-west of England, has invested £22 million restoring uplands bogs since 2005 because these natural systems are cheaper and more effective in removing pollutants and in particular the tiny particles that can make water coming down from the hills turbid.

Bogs are particularly unique places, adapted to extremes of climate and especially areas of high rainfall, and so are home to unique wildlife. However, these amazing feats go into reverse when peatlands are damaged.

Small but mighty

Degraded peatlands emit billions of tonnes of greenhouse gases, estimated to be 5% of total global emissions. In Ireland the emissions from the great expanses of bare, afforested, burnt or over-grazed peatlands are not fully accounted for in our annual reporting to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

However, that will change in 2026 when a more rigorous reporting regime is to be introduced. Some calculations which have been done to-date are finding that this could mean a possible ten-fold increase in our reported emissions under this category[iv]. Early in 2021 it was announced the Ireland would begin voluntarily reporting emissions from ‘managed’ peatlands and wetlands. This will include farmland on peat soil as well as mined out industrial sites but excludes uplands peats or certain areas where there is turf-cutting for domestic fuel.

The good news is that peatlands can be restored. Removing pressures and blocking drains that were installed to dry them out is laborious, but it works. Research from Scotland, where large-scale peat restoration began in the 1990s in the Flow County to the far north, showed that after 16 years the bogs switched from emitting carbon to removing it from the atmosphere.

Initiatives which sound like they are good for the climate – such as wind turbines or forestry – may be doing more harm than good when they are on peatlands. These days, it is widely acknowledged that rewetting peatlands is the most impactful action we can take to stop the haemorrhaging of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere from these landscapes. It is a view reflected by every peatland scientist that I spoke to for this project.

One of those, Dr Catherine Farrell, used to work for Bord na Móna but is now a researcher at Trinity College Dublin. She completed her PhD on peatland restoration in the early 2000s and is a self-described ‘bog woman’.

Her work was based in the far north-west of Co. Mayo, at Bellacorick, a vast expanse of Atlantic blanket bog and one of the few of this type which was subject to the industrial extraction techniques more familiar to the midlands.

“At the time we were trying to bring life back to an industrial landscape” she tells me. “We were blocking drains and reshaping berms to stop water running off the land and carrying peat and underlying glacial sand with it. The Owenmore River is important for salmon so by rewetting the bog we were also protecting the river habitat – it’s all connected.”

Catherine was captivated by the landscape in this relatively little-known part of Ireland. “It felt exotic, it definitely has a wilderness feel to it. I spent a lot of time on my own, surrounded by this vast expanse of bog… and I loved it.”

Her work allowed her to see, and document, how nature could recover all by itself once the conditions were right. “Bogs are designed to hold on to water so our work was based on the basic principles of bog systems” she says. “We wanted the water to stay on the land and where we managed to do this – not too much, not too little – we could soon see the sphagnum establishing itself.”

Sphagnum is a collective term for a family of mosses which are sometimes known as the ‘bog-builders’. As they recolonise the drains and bog pools, they establish a healing layer of vegetation across the scarred land, slowly allowing other bog species to take a hold. “Our first trial plots were in 1997. By 1999 we could see visible results. But you have to work with the system, this is not gardening,” Catherine tells me. “It’s incredible. Moss can grow an entire landscape. But you need to give it time and you have to leave room for the unpredictable.”

Sphagnum moss can build whole landscapes

At the time, Catherine says, few people saw the potential of entire landscape restoration. When she went on to work for Bord na Móna she brought this vision to the industrial bog sites in the midlands but admits it was sometimes a battle to change people’s minds. “Some in the company really wanted to see restoration work being done, others were fearful. But sometimes you have to dig your heels in”.

Catherine built up a team of ecologists which set about mapping the sites and developing the works that needed to be done to restore wet conditions. Machine-workers, who had been employed on taking the peat out of the bog, were perfectly skilled in the delicate work required to block the drains and reprofile the land.

By 2018, Catherine and her team had 15,000 hectares of bog either restored or under ‘rehabilitation measures’ but impressive as this is, it represents just 18% of the 80,000 hectares owned by Bord na Móna, which itself is just about one third of the total area of bog in the midlands. I ask her how far she thought we should be going with this idea: “There are no significant challenges to rewetting and/or rehabilitating all of the midland’s bogs. The main issue will be dealing with adjoining landowners given that most lands beside the Bord na Móna bogs were drained when the initial bog drains went in. So, we have to work beyond the boundary where we can and within our confines where we must, as it were. But even within these constraints, we have an unprecedented opportunity before us to deliver for nature, water, flood mitigation… all of the web of life can return and people are very much a part of that.”

As a climate solution it’s important in the first instance to keep the carbon where it is. That means stabilising the peat by rewetting it. When it comes to actually removing carbon from the air, however, it’s complicated. It’s not always clear that the conditions for actually growing peat will prevail.

There is virtually no chance that the raised bogs will re-form where extensive mining of the peat has occurred, instead, on these ‘cutaways’ we will get something different – fens, embryonic bog-forming communities of plants, wetlands, open water, wet grasslands and wet woodlands.

Carbon can be released even from healthy bogs if there are prolonged droughts in summer. Methane, a greenhouse gas which has 25 times more heating potential than carbon dioxide, can be released from decaying vegetation in ponds and lakes. However, despite the complexities, re-wetting and having a skin of vegetation on dryer areas is the best way to manage the land for climate and other benefits.

Essentially, we need to let nature do the heavy lifting. “We shouldn’t impose our will on nature – it won’t work”, Catherine says. “There will always be parts of the bog which can’t be rewetted because they’re on higher ground. But here you’ll always see moss coming in, then rushes, and that forms a nursery for tree seedlings so you’ll see willow and birch come in in a process of natural regeneration on these drier areas. Natural regeneration is best – peatland plants grow into the place and transform it as they grow; the system evolves. We definitely don’t need to be planting trees! In my experience of working on bogs across Ireland, working with nature is best. Give it the starting point and support its needs – stop the causes of degradation and replace that with wise use and management where required. Or leave it to its own devices. Every site is different. Nature takes time, but nature works!”

Are we ready to let go of the bogs? For many in rural Ireland burning turf is a cultural signature, an intimate part of their identity which is revived by its distinctive smell wafting on a still winter evening.

It’s the rough feel of the sods in the hand as they’re tossed in the hearth and perhaps the memory of elders who spent long summer days on the bogs ‘saving the turf’. Yet the dark side to burning turf is not only the damage inflicted to climate and biodiversity.

According the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) 1,180 people die prematurely due to air pollution in Ireland every year. The main culprits are exhaust fumes from motor vehicles and burning solid fuels like coal and turf.

The latter is not just confined to outdoor areas on smoggy November nights but soot from open fires is also contaminating lungs inside homes. The EPA found that homes which burned peat had indoor carcinogenic pollution levels in excess of World Health Organisation limits. In some towns and cities smoky coal is banned but turf gets a free pass due to its cultural connections (and, no doubt, strong lobbying from turf-cutting contractors inside the Dáil, at least one of whom is also a sitting TD).

In 2019 the Irish Times highlighted an EPA study which found that cancer-causing particulate pollution was twice as high in Longford (which burns peat and doesn’t have a ban on smoky coal) than in Bray in Co. Wicklow (which doesn’t burn peat and does have a ban on smoky coal).

Such disparities also reflect households’ access to fuels such as natural gas, which is less polluting but which tends to be only available to those in urban areas. It also reflects historic proximity to traditional turf-cutting plots – 38% of households in Offaly heat their homes with peat compared with only 1% in Dublin.

An Irish Times article in 2019 quoted Paul Kenny from the Tipperary Energy Agency as believing that people who live in rural areas close to bogs view turf as a cheap fuel, yet they could spend up to €3,000 a year on their combined energy from turf, coal, sticks, fire lighters and electricity. “We did deep retrofits on three ex-local authority homes in Thurles [Co. Tipperary] whose fuel bills were €2,400 each. Following the work, these houses were heated for under €1,000,” he told the newspaper.

According to another Irish Times article, an estimated 400,000 households in Ireland suffer from fuel poverty, defined as spending at least 10% of your income on keeping your home warm and comfortable. In 2017 then-Minister for Communications, Climate Action and the Environment Denis Naughten[v] told a conference on Fuel Poverty and Climate Action that “energy poverty is an environmental issue. It is an economic issue that blights lives, and energy efficiency is the most important means of tackling energy poverty”.

Nevertheless, the Irish government’s record on retrofitting homes has thus far been poor. A European Court of Auditor’s study published in 2020 found that funding provided by the EU was used to replace, rather than supplement, Ireland’s home energy-efficiency scheme. The report also found that the scheme, as it was then designed, did not improve the energy rating of most of the homes that were worked on[vi].

Asking people to stop burning turf may at first seem like the opening salvo in a culture war. A massive programme of retro-fitting draughty homes which reduces heating bills, saves lives and creates local employment, on the other hand, may meet with significantly less resistance.

Mouds Bog SAC in Kildare – cutting turf for fuel goes on

Were this cultural shift to come to pass, the scale of opportunity is truly immense. When you look at a map of the boglands you’ll see they do not form one continuous band. Rather, they are peppered in smaller bog fragments forming an arc from east Galway and Roscommon, down the banks of the River Shannon to Tipperary and east to the Bog of Allen in Kildare.

With a little imagination it is not hard to visualise corridors of woodlands, lakes, marshes, reedbeds and riverbanks knitting them all together into one coherent expanse.

The Shannon Wilderness Park, as it is currently proposed, could be just the kernel of the greatest natural landscape restoration project ever seen in Western Europe. There are those who will despair at this idea – imagining that a land not actively worked by the hand of man will mean a land without people.

This notion must be consigned to the last century where it belongs. Restoring the bogs will require active management, with a need for local ecologists and rangers. Not only that, but the very skills needed for blocking drains and reprofiling land to hold water are those of the machine workers who are now fearful for their futures.

Small-scale, nature-friendly farming should be encouraged to revitalise agricultural lands between the bogs. Tourism opportunities will doubtless arise if what is on offer is truly a wilderness experience.

But more than that, the unlimited access to nature that will be afforded to local people will itself be an attraction to companies to invest and to families looking for a high quality of life.

Many towns like Tullamore and Roscommon already have reasonable property prices and less of the urban stresses like traffic and congestion. What if they also had limitless access to safe walking and cycling paths in a rich and varied landscape?

Local communities have much to gain; how can they be convinced? Decision-making in Ireland tends to be centralised, but we have no shortage of active, engaged community groups which are fountain-heads of innovation. Is there a way to harness these forces to forge a new relationship with nature?

Namibia is not a country you might think of as a source of inspiration for Irish bog conservation. Hugging the Atlantic coast of southern Africa it is mostly known to outsiders for its vast desert regions. In fact, it is the driest country in sub-Saharan Africa.

Yet it is from this unexpected location that Chris Uys arrived to Ireland in the late 1990s. Settling with his Irish wife in the midlands town of Abbeyleix (Co. Laois) he tells me that adjusting to rural Irish life brought some challenges: “this was the 1990s” he says. “There weren’t many foreigners in Ireland. I had to register every year at the Garda station as an ‘alien’ under the Aliens Act from 1935!”

Chris – who has lost none of his distinctive Southern African accent in the intervening decades – describes how he set about integrating with the local community on arrival to the small rural town. He joined a local photography club. He applied to do a course as a tourist guide (Abbeyleix at that time was one of a number of designated Bord Fáilte ‘heritage towns’) and this gave him an insight to Irish history and culture. He got a job within nine months of his arrival.

He recalls at the time that the town had a heritage centre but it was not financially viable; tourist buses on their way to Kerry didn’t stop in the town but money was available for amenity projects such as walking trails and there was an energy to the town. It was at this time, he tells me over coffee in the Abbeyleix Manor Hotel, that the “the bog situation blew up”.

The Abbeyleix Bog can be found to the south of the town, right beside the hotel in fact, and up to the 1970s it had been an area where locals and employees of the nearby De Vesci estate cut turf by hand for burning in their homes. In the mid-1980s Bord na Móna bought the bog from the estate and set about clearing vegetation and digging drains in preparation for industrial peat mining.

However, mining works didn’t go ahead at that time. In early 2000 however it appeared that Bord na Móna were to set to move in again. “We heard that drains were to be dug across the bog”, Chris recalls, “but there was no planning application sign and an ad in the local newspaper didn’t mention Abbeyleix, the community had been left totally in the dark. We went to the EPA [Environmental Protection Agency] to check their file but there had been no communication with them from Bord na Móna. Then in June 2000 we got a tip-off that machinery was about to move in – so we blockaded the entrance with an old crane”.

Abbeyleix Bog – the community built this

The ‘we’ Chris refers to was a strong contingent of local people – up to 100 by one account – who were not happy that industrial peat extraction was about to commence on what they saw as an area of high heritage and amenity value to the town.

While Bord na Móna had been popular in the area, particularly as a long-standing source of local employment, at that stage “the writing was on the wall” says Chris. Local values were shifting, with other sources of employment and greater levels of ecological awareness and in particular the great value of bogs. And so, over the space of a single weekend, the community came together in support of protecting the bog.

But the battle was just beginning, and it would be 2008 before Bord na Móna finally agreed to abandon their plans completely. By that stage the community of Abbeyleix had not only organised themselves but had assembled an impressive team of ecologists, photographers and environmental scientists as well as forming collaborations with national wildlife organisations and state-bodies like the EPA.

Today, Abbeyleix Bog is not only a much-loved local amenity, with its boardwalks and information signs, but has seen significant restoration works including drain-blocking and volunteer-led workdays to remove alien invasive species. A survey by peatland scientists in 2020 found that since works commenced, the area of active bog (i.e. where the peat layer was growing) had grown from 1% of the area to 13% – a phenomenal achievement.

Thanks to people like Chris and others in the town, Abbeyleix Bog is a shining example – perhaps the best we have in Ireland – of community-driven conservation. Yet their work is not done; the bog still has no formal protection in law. “We’re still waiting on a signature,” Chris says in referring to their effort to have the bog designated as a Natural Heritage Area, something that would give the bog a legal status and which is awaiting ministerial approval.

Chris went on to join the Community Wetlands Forum, which had been established in 2013 to facilitate locally-led conservation projects and promote collaboration not only with each other but with universities and state agencies. “We need community engagement,” Chris asserts but he feels there is still too much resistance among state-players. “We need enabling laws to allow communities access to decision-making. Communities need to have the power to decide their own destinies.”

He thinks a lot more needs to be done to join the dots with wider issues. “We can’t look at things in isolation. We have the Sustainable Development Goals from the UN [which identify the need to tackle seemingly disparate issues, like equality and climate change, in parallel] but they’re not being talked about. They don’t get a mention in any of the political party’s manifestos!” (at the time we spoke in January 2020 Ireland was gearing up for a general election).

Chris gets to talking about his home country and how we can learn from how issues surrounding nature conservation have been addressed there.

Namibia, he tells me, came out of a dark period after winning its independence from South Africa in 1990. The previous century had seen a brutal period of German colonialism, followed by apartheid and a civil war which had been on-going since the 1960s.

While the Earth Summit was going in in Rio de Janeiro in Brazil in 1992 the Namibian political establishment was putting their country together. The parties worked hard to build a consensus for a new constitution across diverse ethnic and political lines.

It was based upon human rights and democracy but it was progressive in other ways. Article 95 of the constitution declares that: “The State shall actively promote and maintain the welfare of the people by adopting [among other things, the] maintenance of ecosystems, essential ecological processes and biological diversity of Namibia and utilization of living natural resources on a sustainable basis for the benefit of all Namibians, both present and future…”

Imagine that: a constitutional document that directly links the welfare of its people to that of its nature and biodiversity, and which protects this relationship for the generations which are yet to come! The Irish Constitution, in contrast, has no mention of nature, biodiversity, ecosystems or future generations.

The Namibian Constitution has proven to be more than just fine words. In 1996 the government established a law to allow communities establish their own wildlife conservancies.

This allows for the management of communal land as well as collaboration with private companies in tourism initiatives. It is entirely voluntary; communities must submit a map of the area they want to manage along with a list of community members and the objectives they hope to achieve. The establishment of the conservancies is sanctioned by the Department of Environment in the capital, Windhoek, but any revenue earned stays within the community.

The result has been an astounding success. After decades of over-exploitation of big game, wildlife populations are rebounding, including elephants, black rhinos, lions and leopards. Namibia has the largest population of cheetahs in the world as well as growing numbers of other endangered species.

Poaching has dramatically declined as good wildlife management is seen as integral to livelihoods. Conflict with big predators is managed through the conservancies, which can pay out compensation, replace livestock or implement innovations which deter predator attacks (check out the inspiring TED talk featuring a young Kenyan who invented a simple configuration of flashing LED lights which successfully deter lions from attacking cattle in their pens).

Today, Namibia is a shining light of conservation hope – fully 42% of their land is protected along with 12,000km2 of marine conservation area.

Protected areas are divided between national parks under state administration (18%) with a near-equal area (17%) with community conservancies and includes the protection of the entire coastline.

According to the Nature Needs Half project established by conservationist Edward O. Wilson “by connecting its people to their environment through conservancies, community forests, and community management, Namibia is becoming a country of environmental stewards”.

It is an example to us here in Ireland, and perhaps especially to the communities across the Shannon region, of how new ways of seeing can bring new life and a new future to the people who live there.

Artwork by: Jacek Matsiak

[i] The Children of Lir by Katharine Tynan. From Woven Shades of Green’ Edited by Tim Wenzell. 2019. Bucknell University Press.

[ii] ‘The Utilisation of Irish Midland Peatlands’. 1989. Proceedings of a Workshop held in the Royal Dublin Society from September 21-24 1988. Edited by C. Mollan. Royal Dublin Society.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Wilson et al. 2015. Derivation of greenhouse gas emission factors for peatlands managed for extraction in the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom.

[v] Denis Naughten held this post in cabinet from 2016 until 2018, when he resigned after being found to have had a number of private dinners with the leading bidder for a lucrative national tender for the rollout of broadband services.

[vi] ‘No energy rating rise for half of homes given grants’ by Daniel Murray. Sunday Business Post. May 3rd 2020.