“Do you remember, one day down in the glen you found a poor little wolf in great agony and like to die, because a sharp thorn had pierced his side? And you gently extracted the thorn and gave him a drink, and went on your way leaving him in peace and rest?”

“Aye, well I do remember it,” said Connor, “and how the poor little beast licked my hand in gratitude.”

“Well,” said the young man, “I am that wolf, and I shall help you if I can, but stay with us to-night and have no fear”

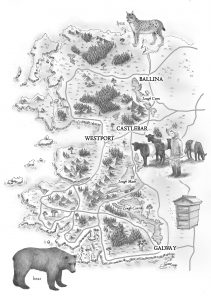

Artwork by: Naomi McBride

Mac Tíre: son of the land; the Irish name for the wolf that tells you all you need to know about the heritage of this animal which still today inspires such awe and fear.

Well over 200 years since the last wolf was exterminated in Ireland emotions still run high at the mention of its name.

It’s not all negative; many are enthralled at the idea that wild wolves might once again roam the countryside. But many still think that the idea is so preposterous that we may as well talk about releasing fire-breathing dragons or scaly velociraptors.

Deep in our subconscious the wolf of ‘little red riding hood’ is the embodiment of all evil, a clear and poorly-disguised threat to our way of life.

The wolf is wild nature: something we’ve driven out long ago in a clear and defining victory in man’s battle for dominance of the land.

Centuries after we successfully drove it to extinction on our island, and indeed extirpated it from much of the Western world, we still need to remind ourselves of the significance of this victory – just watch the 2012 Liam Neeson film The Grey with wolves relentless in their blood-lust, eyes alight with Lucifer’s flame in the darkness.

But it wasn’t always like this.

In A Wolf Story Connor is a young farmer who awakes to discover that two of his best cows are missing. He searches in vain the fields and woods beyond his pastures. As twilight approaches he happens upon a shieling (a ramshackle hut) in the desolate heath, knocking on the door where beyond a light is shining through cracks in the boards.

The door is opened by a “tall, thin, grey-haired old man, with keen, dark eyes” and an “old, thin, grey woman, with long, sharp teeth and terrible, glittering eyes”.

“You’re welcome” she gestures to Connor, “we have been waiting for you – it is time for supper. Sit down and eat with us.”

Unnerved, but tired, lost and hungry, Connor sits. Then, a knock on the door. The old man rises only to admit “a slender, young black wolf” who retreated to a back room only to reappear moments later as a “dark, slender, handsome youth”.

Two more knocks, two more wolves, two more handsome young men.

“These are our sons” said the old man, “tell them what you want, and what brought you here among us”.

Connor told them how he lost his best cows but “they all laughed and looked at each other, and the old hag looked more frightful than ever when she showed her long, sharp teeth.”

Angry at being mocked, Connor raised his stick and made for the door but was calmed by the eldest son, who recounted how as a cub, Connor had saved him from a life-threatening thorn in his paw.

“We never forget a kindness” he assured Connor. Connor awoke the next morning in his own field. On checking his paddock he found no sign of his cows and, disappointed, he thought the wolf had let him down. But then, in the field close by he found “three of the most beautiful strange cows he had ever set eyes on”.

Believing them to have strayed on to his land he went for his stick to drive them back but when the cows were at the gate “there stood a young black wolf watching; and when the cows tried to pass out at the gate he bit at them, and drove them back. Then Connor knew that his friend the wolf had kept his word. So he let the cows go quietly back to the field; and there they remained, and grew to be the finest in the whole country, and their descendants are flourishing to this day, and Connor grew rich and prospered; for a kind deed is never lost, but brings good luck to the doer for evermore.”

Try as he might, Connor never found the shieling on the heath so that he could thank the wolf family to which he was indebted, “though he mourned much whenever a slaughtered wolf was brought into the town for the sake of the reward, fearing his excellent friend might be the victim”.

I love this story because it does not romanticise wolves; we don’t know, after all, what fate befell Connor’s original lost cows. And it shows a respect and a willingness to let each other be that is near-absent in our dealings with the natural world today.

I don’t know when this story dates from but since it refers to the rewards which were placed on the heads of wolves it is likely to be from the 1700s. Old but not ancient.

It hints at the changing attitudes towards wolves at that time as older stories are less likely to feature the air of menace which surrounds the animals to this day.

Very old Irish stories include examples of infants reared by wolves as well as wolves conversing with saints, or saints feeding starving wolves from their sheep flocks.

The Brehon Laws which were in force in Ireland up to the Middle Ages included strictures on bringing your livestock close to known wolf dens. If you drove your neighbour’s animals near the wolves, and a cow or sheep was lost, compensation had to be paid[ii].

It clearly shows that a way to coexist with wolves had developed and there was no desire on behalf of the people to eradicate them from the land. It shows a deep and ancient wisdom in our dealings with nature, something which is reflected in modern programmes sponsored by the European Union which promote livestock farming alongside the conservation of large predators like wolves, bears and lynx – all animals which were once found in Ireland. How are we going to get them back?

We sometimes forget that Ireland has experience of bringing back large carnivores. In the late 1990s golden eagles were reintroduced to Donegal from Scotland while in 2007 white-tailed eagles were brought from Norway to Killarney National Park in Kerry.

These are truly enormous birds, among the largest birds of prey in the world with a wingspan up to 2.5m (if you stretch your arms out you might get to 2m if you are very tall).

Few of us will ever get close to one but we might get to see them in flight where they are sometimes compared to a flying barn door.

Frequently harried by ravens or hooded crows (themselves large birds) we can then get some sense of scale, dwarfed as they are by the giant raptor. Allan Mee is an ornithologist from Co. Limerick who worked on the reintroduction of the white-tailed eagle.

He completed his doctorate in Sheffield University in England and worked for many years for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) as well as Scottish Natural Heritage in the Creag Meagaidh National Nature Reserve (in the Highlands) in 1992/3.

“This was rewilding before rewilding had a name” he tells me. Although established as a nature reserve for its stunning landscape and habitats from the valley floor to the mountain plateau, with important populations of breeding Dottrel, Ptarmigan and other mountain birds, the reserve sought to reverse centuries of land degradation, something which was principally caused by too many deer and sheep eating too much vegetation, including any new tree saplings.

As a result, the valley – like nearly all upland valleys in Scotland and Ireland – were almost totally treeless. A campaign to prevent the planting of a dense stand of the non-native sitka spruce led to the valley falling into public ownership, and thereafter, the removal of sheep and deer. That was in 1985.

“At the time I worked there the lower reaches of the valley were showing real signs of recovery, especially birch, rowan and juniper.”

Allan is describing the remarkable ability that trees have for planting themselves, sometimes called ‘natural regeneration’. Thirty years on, Craig Meagaidh has seen what the non-profit group ‘Rewilding Britain’ has described as “spectacular results”.

Allan went from there to California where he did a post-doctorate research study on the reintroduction of the California condor. Condors are enormous vultures and the Californian species is the largest bird in North America, with a wingspan of an incredible three metres (another species of condor inhabits the Andes Mountains in South America).

By the early 1980s only 21 California condors were known to exist and the decision was made to take the last birds, including eggs and chicks from nests in the wild into captivity as part of a rescue programme – a highly risky and, at the time, hugely controversial decision.

I have vivid memories of this as a teenager; seeing on television how the captive-bred birds were carefully reared with a minimum of human contact. I remember the condor-mimicking hand puppets which were used by zoo staff to feed the chicks so that they would not associate humans with food. In 1992 the first captive bred condors were released back into the wild in the Sespe Condor Sanctuary in southern California.

The most recent count from 2018 put their number at 518, 337 in the wild in California, Arizona, Utah and Baja California, Mexico, and 181 in captivity – a phenomenal achievement even if the bird remains classified as ‘critically endangered’.

Allan was in California during the early years of this project helping to monitor the birds as they repopulated their old haunts. But despite the apparent success, “the population is still not self-sustaining” he emphasises. “The birds range over such huge areas that they are impacted by everything that goes on in the landscape”.

The biggest cause of death of young condors at nests in the wild during the early 2000s was parent birds feeding discarded ‘microtrash’ to their young, possibly mistaken by the parents as bone fragments.

Then, Allan says, “once it became appreciated that the main source of condor mortality was poisoning from the birds eating lead bullet fragments – which they picked up by eating prey remains of deer and other animals killed by hunters – it turned into quite the political battle between government departments, conservation groups and the powerful sport hunting lobby in the US”.

The use of lead in bullets was outlawed in the condor’s range in California in 2008 but remains legal in other states, such as Arizona and Idaho where the condors are gaining a toehold. It shows the complexities of returning animals to landscapes which have been utterly altered by human activity, particularly where the animals – like the condor – range over such wide areas, live to a long age (up to 60 years in this case), don’t lay their first egg until they are six years old and, even then, only rear one chick every other year.

But to me, it also shows what can be done. That the California condor didn’t go extinct is surely one of the great success stories of modern conservation, even if challenges remain.

Allan brought his experience with the condors back to Ireland where he worked on the project to release the white-tailed eagle, run by the Golden Eagle Trust and the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS).

White-tailed eagle. Image source: Mike Brown

It was 2007, and a general election was to be held in May of that year. Allan had made presentations to local politicians and community groups about the reintroduction plan and the local response was widely positive. Yet, there were scare stories doing the rounds about eagles attacking and eating sheep.

For a brief moment, it appeared that the Irish Farmers’ Association were making it an election issue in Kerry, such that the project might be pulled at the last moment. Allan frantically rallied support from tourism interests, which saw the return of the eagle becoming a visitor attraction, and he managed to get the project back on track. It was a close call – 2008 saw the financial crash and drastic reductions in the budget for the NPWS which might have scuppered the project.

Allan notes that while the leadership of farm organisations often present a different face to that of ordinary farmers on the ground, who he found to be more supportive (some went on to become volunteer nest-watchers at some sites), there was also some opposition to the reintroduction from within the NPWS itself.

In the end, of course, it did go ahead but Allan strikes a cautious note: “It’s too early to say the project has been a success”. The eagles can live to reach over 20 years of age but do not produce large numbers of chicks. Initially a number of white-tailed eagles were killed from poisons laid on land for other species (foxes and crows mostly), which then had to be outlawed (Allan notes the importance of political leadership as it happened that the relevant minister at the time was John Gormley of the Green Party, someone who was sympathetic to biodiversity interests).

By 2017 there were 12 nesting pairs of white-tailed eagles in Ireland. In 2018 avian flu killed two females in the Lough Derg area of Co. Clare, leaving a male who is still flying around looking for a partner (the eagles otherwise are known to stay with their mate for life).

In 2019 Storm Hannah hit early in the nesting season and destroyed every eagle nest bar one. But since 2015 there have been no known poisonings and Allan thinks this year (2020) could see nine, or possibly 10, nesting pairs.

With six more chicks from nests in 2020, a total of 32 chicks have now fledged successfully from nests in Ireland to-date. It’s a slow recovery but Allan is optimistic with the further release of young birds from Norway in 2020-2022 to bolster the existing population.

Ireland has lost at least 110 species of plant and animal since the arrival of humans many thousands of years ago (I say ‘lost’ but ‘exterminated’ would be more accurate).

It’s a calculation I made when researching ‘Whittled Away’ that is almost certainly a gross underestimate since the extinction of many species is likely to have simply gone unnoticed and unrecorded.

These range from bears, right whales and sturgeon (an enormous fish of estuaries and slow-flowing rivers), to tiny mosses and beetles which live in dead or dying trees.

If we were to reintroduce one species per year to rectify this haemorrhaging of biodiversity it would be the year 2130 before Ireland’s wildlife community could be said to be whole again.

In the ten years from 1997 to 2007 three birds of prey were reintroduced: the white-tailed eagle, the golden eagle and the red kite.

But there have been no reintroduction programmes since then. Great-spotted woodpeckers and buzzards have reintroduced themselves while goshawk and marsh harrier may be gaining a foothold.

There is a possibility of natural recolonisation for a number of other bird species, such as cranes or osprey, which can fly and occasionally turn up on our shores (but no confirmed nesting to date).

Natural re-colonisation may also work for marine species such as halibut, sturgeon, wolf fish and even the critically endangered northern right whale which all could swim into our waters. But if we want to re-establish natural ecosystems in Ireland we’re going to have to get a lot more pro-active.

Large animals like bears, capercaillie, lynx, wolves, wild cats, wild boar or even many of the smaller insects or plants which are not capable of travelling large distances, will need our help.

Many people will point out that we can’t simply plonk these animals into landscapes which have been so completely altered by human activity. I put this to Allan.

“In some cases, yes, the ecosystem needs to be restored first” he says. Capercaillie [a large grouse which needs expansive areas of undisturbed woodland] cannot be brought into Ireland right now because the habitat simply isn’t there for them. On the other hand, the missing species are needed precisely in order to restore the ecosystem. Wolves, for instance, can help grow the forest by keeping the grazers in check but the problem here is human acceptance; there’s plenty of habitat for them”.

And how far do we go? Can we return bears when the last of their kind went extinct from Ireland thousands of years ago? Should we launch into a reintroduction programme for lynx even though the evidence that they were even in Ireland is so scanty (a single, nearly 9,000-year-old femur)? Should we be looking at bringing animals into the landscape for which there is no evidence that they were ever even here, like the beaver and wild horses?

The lynx belongs in Ireland. Image source: NickyPe via Pixabay.

“Ireland’s ecology is very similar to Scotland” muses Allan, “we shouldn’t be hung up on the lack of evidence. Lynx has a place in Ireland. Beaver…” he trails off… smiling to himself.

My own view is that beavers would make a fine addition to our landscape. They would help to restore the wetlands along with our damaged river systems, helping to clean water and reduce flooding. I’m sure they would fit right into the Shannon Wilderness Park with its dense network of wetlands.

But this conflicts with accepted scientific advice which is clear that reintroductions should only occur where there is evidence that the species was once present.

Then again, the advice (from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature) also sets a totally arbitrary cut-off year of 1500. They suggest that species which went extinct before that date should not be reintroduced. This clearly makes no sense. We’re also pretty relaxed about releasing large numbers of non-native and sometimes invasive species into our landscape, like pheasants, Pacific oysters or cherry laurel bushes, with no checks, licencing or ecological assessments.

It reminds me of the quote from Aldo Leopold who said:

The game manager who observes, appraises, and manipulates these half-known properties… of wild creatures is playing a game of chess with nature. He but dimly sees the board, the men, or the rules. He can be sure of only two things: for intricacy and interest, any other game pales into insignificance; he must win if wildlife is to be restored.[iii]

—

It’s July 2019.

I’m at the Loch Garten Osprey Centre which lies within the Abernethy National Nature Reserve in the Scottish Highlands and through the telescope I am watching one of the eponymous ospreys nesting in a clearing.

These birds of prey are specialist fish-eaters and their adaptations include closable nostrils to stop the water getting up their noses as they plunge for their prey.

Ospreys are referred to by biologists as ‘cosmopolitan’, that is, they are known from nearly everywhere, including all of the continents except Antarctica along with all of the temperate and tropical zones and even some of the island groups of the South Pacific.

The osprey is thought to have been driven out of Ireland sometime in the 1700s perhaps because it was seen as a threat to fish (although few of our birds of prey survived into the 20th century because they were all seen as a threat to something by the landed classes).

They disappeared in Scotland too but then, in 1954 they reappeared, right here in Loch Garten. Not only have they stayed here but there are now around 250 pairs breeding in Scotland and are they expanding into sites in England.

The RSPB visitor centre, just off the loch and nestled within groves of ancient pine trees, gets about a million visitors a year – people like me who come to stare through the telescope to see the birds bringing fish back to the nest to feed their young.

The Abernethy forest is among the largest remnants of Scotland’s ancient Caledonian pine woodland. Scotland, like Ireland, has a history of near eradication of its native woodland, which today stands at around 4% of its land area (in Ireland its less than 2%).

Abernethy was lucky to escape the axe (deforestation occurred right up to the Second World War) and today it is home to some truly ancient giants, or ‘granny pines’ as they’re known locally.

I stayed for a week in a rental house in the forest itself and it was a magical experience. In the evening roe deer emerged from the woodland to feed on the grasses while hikes took us deep into the woodland in the company of the granny pines. Somewhere amongst these trees lie wild cats and capercaillie – two more species which were once found in Ireland.

Like in Ireland, the capercaillie went extinct in Scotland in the late 1700s and, also like Ireland, were reintroduced with birds from Sweden in the 1800s.

But unlike Ireland, the Scottish birds endured, although climate change, deer fences and predation from small predators like pine marten and fox means they remain a threatened species.

The wild cat too is critically endangered in Scotland, perhaps only 30 genetically pure animals remain. In essence, the pine forest, entrancing as it is, is just too small. The populations of species that depend upon it are hemmed in and vulnerable to what would be small impacts were their numbers larger.

But Scotland, unlike Ireland, has a plan.

The Eurasian beaver

‘Cairngorms Connects’, named after the mountain range which includes Abernethy and the Loch Garten Osprey Centre, is a partnership between state agencies (Scottish Natural Heritage and the Forestry Commission Scotland) and environmental organisations such as the RSPB.

It envisages the restoration of native woodlands and wetlands across an impressive 600km2 of the Cairngorms National Park.

Although its timeline is very distant (the brochure includes a vision for 2216!) the idea of joining up fragments of older woodland to create a much larger, landscape-scale forest, is a significant departure from how conservation has been done to date.

Up to now, the approach has been to draw lines around individual sites which are then treated in isolation from the surrounding countryside. It is an approach that has failed, not only in Scotland but particularly in Ireland, where the management of these sites has rarely moved beyond the drawing of lines on maps.

The idea behind Cairngorms Connects is scale and if we are serious about a future where humans live within flourishing and healthy nature we need to be thinking big – really big!

The main town for exploring the Cairngorms area is Aviemore. It reminded me a bit of Killarney in Kerry, with its Victorian heritage harking back to the days of the first tourists in the 1800s.

There’s a funicular railway to the summit of Cairn Gorm (1,245m) which opened in 2001 at a cost of £26 million and with a fair degree controversy due to the intrusion of a railway line across the delicate alpine habitat.

It was closed at the time I visited in 2019 due to what the BBC called ‘structural problems’. The funicular not only brought day trippers to the top of the mountain it also brought would-be skiers.

A ski resort first opened on the Cairngorms in the early 1960s but climate change means that these days the operators of the resort must use snow cannons to keep some of the slopes open.

In December 2019, 100 tonnes of snow were being manufactured every day using a ‘snow factory’ machine. It has been such a fiasco that earlier that year there were calls to have all the skiing infrastructure “stripped out” and the slopes “returned to their natural state.”

In summer the National Park areas around Aviemore are busy with tourists, with lots of walkers on the easier trails, camping and caravan parks and water sports along the River Spey while large areas of hillside are under active forestry management with blocks of single-aged conifers and commercial clear-felling.

In this regard, it also reminded me of Killarney and other heavily visited parts of Ireland where the landscape has been largely industrialised even if it maintains a veneer of naturalness for marketing purposes.

The only wildlife visitors are likely to see in these areas are on the posters designed by the tourism authorities. Yet not far beyond the busy centres of activity there are large glens which stand in stark contrast.

Unlike in Ireland, Scotland – like the rest of Britain – has an extensive network of off-road walking trails which are well sign-posted and maintained. A long walk through the Rothiemurchus estate to Loch Eanaich with its granny pines and wooded hillsides is a tonic and leaves me longing for a similar experience in Ireland.

In fact, while Scotland has its issues, it also has its ospreys, capercaillie, wild cats, substantial new areas where natural woodland is returning and, most importantly: a vision for the future.

Ireland struggles to accommodate this vision and is so stripped of its wildlife that it feels like walking through an art gallery where only the shadows of the paintings are visible against the bare walls.

“Rewilding… it’s the business of selling hope… rewilding represents that”. I had followed the winding road through the forest south of Aviemore to visit Peter Cairns.

Peter is director of ‘SCOTLAND: The Big Picture’ a charity that advocates for more wildness. He’s a superb photographer and his stunning images bring to life the beauty and wonder of Scotland’s wildlife.

He believes that the key to rewilding, if it is to be a success, is effective storytelling. “Rewilding is more than just a set of actions or goals, it’s anything that brings us towards a wilder future” he tells me.

“The ‘need to manage’ is completely tied up with the meaning of ‘conservation’… but implicit in rewilding is recognising that people are a part of nature. For us to be deciding which plants and animals get preferential treatment is ‘speciesism’ – what we should be doing is prioritising ecological processes.”

Rewilding has had a bumpy road in Britain in the last ten years. On the one hand, it has received a lot of public attention and this in turn has brought funding. Rewilding Britain, a non-governmental organisation established in 2015, cites 13 places across England, Scotland and Wales where rewilding is under way. The organisation says it is based on four principles: ‘people, communities and livelihoods are key; working at nature’s scale; allowing natural processes to drive outcomes; and ensuring benefits are for the long term.

However, it has not been all plain sailing.

One of their projects, Summit to Sea, in Wales was setback in 2019 when one of its funders withdrew support.

The project had met with a hostile reaction from farmers in mid-Wales with the Farmers Union of Wales telling the BBC that “there’s every scope for working with organisations that recognise the importance of farming and the dangers to our eco-systems of getting rid of farming from habitats in which they’ve operated for thousands of years. There’s no room for working with those who wish to see land abandoned on a huge scale.”

Back in Scotland, Peter Cairns acknowledges that “the challenge is the people stuff”.

Although people like Peter and organisations like Rewilding Britain repeatedly emphasise the potential benefits to rural communities, attitudes among these communities – in some places at least – are hardening.

“Rewilding is not de-peopling” Peter stresses to me but he recognises that these perceptions will be hard to shift. Especially so in the Scottish Highlands which have a history of forced land clearances from the mid-18th century through the mid-19th century.

This dark period of Scottish history saw the eviction of thousands of families from their land, their property destroyed and involuntary resettlement to poorer land.

Ironically from a rewilding point of view, this was done to make way for sheep farming, today seen as responsible for much of the ecological destruction of hillsides in Ireland, England and Wales.

In Scotland the sheep gave way to vast estates devoted to deer stalking and grouse shooting, which, in their own way, perpetuate the ecological devastation to the landscape.

Because the Scottish Highlands have such a low population density (11 people per square kilometre versus 274 people per square kilometre in Britain as a whole) it is seen as the most likely place for any future reintroduction of large predators, particularly wolves.

But talk of wolves seems to enflame existing tensions.

“We of course support the idea of bringing wolves back to Scotland but you could waste an awful lot of time and money arguing about them” says Peter.

He tells me they are working on bringing back cranes (extinct from Scotland for several hundred years but nesting once again in England following a reintroduction programme there) and he thinks that bringing back lynx would attract less controversy than talk of wolves. “There’s plenty we can be getting on with for the foreseeable future without getting bogged down in the wolf debate”.

Peter suggests I take a visit to the nearby Glen Feshie estate, which is owned by the Danish textile magnate Anders Holck Poulsen (whose holding includes familiar clothing retailers Jack & Jones and Vera Moda).

Glenfeshie

His wealth is an estimated $6 billion and is now the largest single landowner in Scotland. Poulsen is among what the Sunday Times has labelled “an intimate network of the super-rich who invest in the environment… Club Billionaire, dedicated to saving the world”.

The group includes Hansjörg Wyss, a Swiss octogenarian who in 2018 gave $1 billion to conservation with the goal of protecting 30% of the Earth’s surface by 2030; Paul Lister, who inherited his fortune after his family sold the UK’s largest furniture retailer MFI (and who proposed releasing wolves on his 9,300 hectare estate at Alladale in Scotland but wasn’t allowed because erecting large fences would have contravened Scotland’s right to roam laws); and Charles Burrell, owner of the Knepp Estate in West Sussex with his wife, the author Isabella Tree, whose book ‘Wilding’ describes the transformation of their 3,500 acre estate from a sterile industrial farm to a landscape heaving with wildlife as well as free roaming cattle, horses, pigs and deer.

The group included the founder of clothes brand North Face and Esprit, Doug Tompkins, who used his fortune to buy up a whopping 1 million hectares of land in Patagonia before tragically dying in a kayaking accident in 2015.

The Sunday Times article describes how the group had coalesced around an idea to buy, and subsequently protect for nature, a massive 200,000 hectare national park in Romania with bears, wolves, bison and lynx – what they envisage as a ‘European Yellowstone’.

It describes how Lister convinced Poulsen to take a helicopter ride across the Carpathian Mountains, surveying maps of the region and deciding on the spot to buy up a 250km2 tract of land. The project would protect the land from illegal, mafia-style loggers and promote local tourism initiatives they said. Yet one of the group conceded at the time that “we still have to convince the Romanian state to buy into the concept.”

If I were a billionaire I would surely be tempted to use my wealth to buy large tracts of land in the west of Ireland in order to lord over an exciting rewilding project with bears and wolves. In 2019, Kristine Tompkins, Doug’s widow, oversaw the largest donation of public land in history when two vast areas of Patagonia were handed in trust to the Chilean state. So, I don’t doubt the motivations of this cohort of the super-rich.

Yet, this approach leaves me with a deep sense of unease. A significant reason why we have a climate and biodiversity emergency can be pinned to the very fact that we have a growing cohort of billionaires and super-rich.

In June 2020 the scientific journal Nature Communications published an article entitled ‘Scientists’ warning on affluence’ in which it said “the affluent citizens of the world are responsible for most environmental impacts and are central to any future prospect of retreating to safer environmental conditions”[iv].

We can’t untangle that from the generally low wages of farmers in Ireland or Romania who work these lands or even the violent land clearances in Scotland in centuries past.

I take Peter’s advice and spend the next day hiking through Glen Feshie. Since the heavy culling of deer began in 2001 there has been a widespread re-emergence of trees and an incredible recovery of the Caledonian pine forest.

It’s part of the wider Cairngorms Connects initiative and will be a considerable boost to the perilously endangered wild cats and capercaillie of the region. It’s a beautiful and inspiring place. But it is not a template that I would like to see transferred to Ireland.

—

Bridgi Murphy knows a thing or two about sheep farming in the west of Ireland and co-existing with wild animals – though not necessarily at the same time.

Although born in South Africa, Bridgi comes from nine generations of a hill farming family in the Ox Mountains in Co. Sligo.

“Irish people don’t know what wildlife is! I grew up tipping wellies out before putting them on in case there was a snake, scorpion or poisonous spider inside” she says.

Bridgi’s grandmother emigrated from Sligo to England, her mother in turn taking the boat to Australia. But a chance encounter with a merchant sailor in Cape Town, South Africa prompted her to jump ship and, shortly thereafter, get married.

Bridgi was active in the anti-apartheid movement when she studied law in university in the 1980s, then moved to working in rural areas with Zulu communities – helping them fight evictions and claim back land lost to apartheid.

“There weren’t many of us doing that work in those days” she mused.

Her parents moved back to Ireland in the mid-1990s and Bridgi came to visit them a few years later. “The first time I stepped on the land I knew I had come home” she says.

So, in the company of her young daughter, Skye, she returned to the very fields of her forebears.

“We came up the hill to live in a mobile home with no telephone, no electricity, no running water, a very narrow lane, and a tiny roofless stone shed… but it was right, I felt a very strong connection to this land.”

Since then Bridgi has been farming sheep, ponies and bees across a few fields of grassland and a share in a heathery commonage higher up the hill. But despite her passion and sense of connection to the land she tells me that “it’s an enormous struggle physically and emotionally for no financial return”.

She would rather farm bees and native wildflower seed, keeping fewer sheep and grazing them with agro-forestry or native woodland. She already keeps a small nursery of native trees which she plants annually along her waterways and ditches. “We’re stonewall country up here, rather than hedgerows” she explains. Her daughter, Skye, has no interest in farming but nevertheless retains the connection to the land. “Living with and on the land is something we’re linked to, but, like me, she would rather return it to nature”.

This comment is a revelation to me.

In Ireland, connection to the land and farming are seen as effectively the same thing. The ideas are so welded to each other that many would assert that you cannot have a connection to the land unless it is being farmed.

If it’s not farmed then it is neglected, abandoned or looked upon as wasteland.

And yet, in an age when young farmers are as endangered as the curlew and the golden eagle, here is a young person determined to nurture her roots but in a radically different way: belonging to the land which itself belongs to nature.

This is not to say that I would like to see all farming disappear. In fact, my ideal rural landscape is a mix of small, close-to-nature farms alongside areas that are only for nature. But, does farming have any future on these hills?

“For the majority of family farms, certainly not under the current system” says Bridgi. The distribution of the CAP [the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy] budget has been dreadful for hill farmers up and down the western seaboard. Families here, sheep and beef farmers alike, have had to get an off-farm job to survive and that means they have had less time to spend tending the land. Efficiencies like contractors, big machinery, and ‘smart’ farming become important and rearing animals in the most efficient way takes priority. It has been dreadful for nature too, more chemicals and sprays and less food for anything that lives on the land as we mow and cut long before anything seeds or fruits. For the last twenty years, I’ve been hearing farmers telling their children to go off and get a degree and not to waste their time working so hard for nothing as they have done.”

I first met Bridgi in 2017 when she was an active member of the Irish Natura and Hill Farmers Association (INHFA), a lobby group which split off from the much larger Irish Farmers’ Association (IFA) due to what was felt as a lack of representation for smaller farmers on hill land or with nature conservation designations (‘Natura’ refers to the EU’s Natura 2000 network of conservation areas which covers 13% of our land).

The meeting was a notable encounter for two reasons; it was the first time in my then-10 years with the Irish Wildlife Trust that any representative of a farming organisation had contacted us to find out about our views on policy issues (and the last as it happens[v]).

It is also memorable because Bridgi is a woman – anyone watching farmer representative groups over the years will have noticed very few female faces. This is not an incidental detail, it is – Bridgi believes – a central aspect to the homogenous culture of these organisations and something which is reflected in their policies (or lack of them as the case may be).

She points me to statistics from the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine which shows that 57% of on-farm employment is carried out by women but yet, she says, “Our voices are silent. The number of women farmers in leadership positions who sit at, and contribute to, policy-making tables and lobbying delegations can only be described as woeful or downright non-existent. Farmers are not a homogenous group but you wouldn’t think that by looking at who represents us!”

Bridgi is straight-talking and has a grasp of cross-sectoral issues from climate change and biodiversity loss to land tenure and the intricacies of the Common Agricultural Policy, not to mention her personal experience as a hill sheep farmer for over 20 years.

She has remained active in issues close to her heart: land and human rights.

She had originally postponed our conversation to attend the (former president of Ireland) Mary Robinson 6th Annual Human Rights Lecture and to meet up afterwards with a friend, Kumi Naidoo (former director of Greenpeace and Amnesty International).

Among her initiatives was one to have beehives and a field margin set aside for wild pollinators recognised as a livestock unit, thereby making them comparable to heads of cattle or sheep and eligible for EU payments.

As it stands, a hill farmer cannot access some of the available subsidy payments without keeping a mandatory minimum number of livestock.

Yet her approach didn’t go down well with the leadership in the INHFA and in early 2019 the climate and forestry committee on which she served was disbanded.

In fact, despite the increasingly fractious nature of farming groups, we have yet to see any of these organisations embrace climate action or nature-friendly farming as part of a future which also sustains farming incomes.

“The current farming and food system needs to rendered obsolete” Bridgi says firmly. “If farming is to have a future there must be payments to regenerate ecosystems which in turn produces healthy food from healthy soils and healthy animals. Our livelihoods and our rural communities can only be healthy and thrive if they are operating in healthy, thriving ecosystems.”

She lives and works in a landscape which many nature-enthusiasts, myself included, feel would be better rewilded – that is, restored to native forests and wetlands and missing species such as wild boar and wolves reintroduced. I want to know how she feels about this.

“Rewilding is amazing, too many people think ‘wild’ is ‘bad’ but ‘wild’ is essential! The more we’ve tried to control nature the more we’ve destroyed it. To move out of the biodiversity and other crises we find ourselves in, we must allow ecosystems to re-nature and regenerate themselves – at least that’s how I’d describe rewilding. Aspects of rewilding like reintroducing wolves will not work while we continue on our current trajectory, there is too much of a risk that they will target farm animals, which is why many farmers are against the idea”.

Ireland’s recent trajectory has left it far off course for rewilding.

Not only that, that but we are far off course for even meeting the modest conservation goals which were set decades ago – saving entirely harmless bees, freshwater pearl mussels and curlews seems like a task just as daunting as bringing back wolves.

There is one project though that has held out some promise for Irish rewilding enthusiasts. In 2013, to much fanfare, including a photo-op with then Taoiseach Enda Kenny, the Wild Nephin project was launched.

I wrote about it in ‘Whittled Away’ in 2017 as holding exciting promise even if little had been done on the ground at that time.

Since then, the Wild Nephin area, which straddles 15,600 hectares of boglands north of Newport in Co. Mayo, has been amalgamated with the neighbouring Ballycroy National Park. In June of 2018 a ‘Wild Nephin Wilderness Area Conversion Plan (2018-2033)’ was published – a meaty document which set out the vision and how it was going to be achieved.

The plan commits to establishing a Project Steering Group and affirming that local communities will be regularly briefed “through workshops and public meetings”. The plan is quite detailed in how it plans to remove the plantations of non-native conifers and dealing with invasive species, particularly rhododendron which quickly spreads over the degraded peatlands in this part of Ireland.

But most eye-catching is the statement of intent: that Wild Nephin would be an officially designated wilderness area. The plan quotes an EU document which defines wilderness as:

An area governed by natural processes. It is composed of native habitats and species, and large enough for the effective ecological functioning of natural processes. It is unmodified or only slightly modified and without intrusive or extractive human activity, settlements, infrastructure or visual disturbance.

‘Wild’ Nephin

The Wilderness Act in the United States says that a wilderness area should be “at least 5,000 acres of land”, around 2,000 hectares, so Wild Nephin – nearly eight times this size – amply meets this criterion.

Of course, in the US the idea of wilderness was about preservation (and, lest we forget, displacement of indigenous peoples or the landless poor) and recreation, that is, a pastime for those with means.

West Mayo has been inhabited for thousands of years while these days its landscape is largely degraded through deforestation, land drainage and peat mining, industrial forestry and overgrazing by sheep.

The Wild Nephin idea therefore has to turn these issues around and create something completely new, something perhaps which has never existed in the past, even before there were people working the land in Mayo.

The Conversion Plan therefore offers us something we’ve never had before: a definition of wilderness ‘in an Irish context’:

A wilderness is a large, remote, wild (or perceived wild), protected and publicly owned landscape with good visual and natural qualities. A wilderness facilitates humans to experience our connections to the larger community of life through the enjoyment of nature, solitude and challenging primitive recreation, without significant human presence or the intrusion of human structures, artefacts or inappropriate activities while supporting a functioning ecosystem.

A wilderness is therefore generally free from human management and manipulation and is an area which allows natural processes to take place or where, through a process of rewilding, such natural processes are progressively restored, leading to increased stages of naturalness. A wilderness can include modified landscapes that no longer support long term human occupation and/or a viable managed landscape. A wilderness should be a minimum of 2,000 ha offering opportunities for solitude and primitive recreation. [their emphasis]

It’s a tortured and meandering definition but I suppose you get the idea.

There is no mention of local people but the US idea of ‘primitive recreation’ is there.

Rewilding is also there as is the phrase ‘functioning ecosystem’.

What does all this mean?

Is it turning rural Ireland into a theme park – that most worn-out of accusations favoured by some politicians and cast like stones at those promoting nature conservation?

Does it allow for the reintroduction of exterminated species like lynx, wild boar, bears and wolves? The Conversion Plan doesn’t mention them.

The Plan says that ‘consultations’ will be held with ‘key stakeholders’ and that all kinds of committees and steering groups will be established but when I followed up with the National Parks and Wildlife Service in June 2020 (seven years since the launch of the Wild Nephin concept) no such initiatives had been taken.

The Plan barely mentions sheep, an animal referred to by US wilderness pioneer John Muir as “hooved locusts” and which have wrought so much harm to hills and bogs of the west of Ireland.

In 2018, the environmental website www.greennews.ie revealed that despite agreeing to phase out commercial forestry in the area, 260,000 non-native pine trees were planted between 2013 and 2017. Although the sign posts have gone up and the brochures have been printed, actual initiatives on the ground since 2013 have been limited and/or kept quiet.

When I decided to undertake this project in 2018 I tried to imagine the most ambitious vision for bringing nature back to Ireland that I could conjure.

This, I decided, was not reintroducing wolves – an idea which is slowly entering the mainstream – but bringing back brown bears.

Bears are big animals. Unlike wolves they are not so adaptable to the human presence; they cope poorly with fences and other barriers, roam over huge areas and actively avoid human contact, even in areas where activity may be limited only to hiking and camping.

There’s no doubt that bears belong to our native fauna but whereas wolves really only require people to tolerate their presence (and bears would require that too!), bears present some significant logistical challenges.

On the other hand, when conservation efforts are made, these are generally successful. France has been undergoing a bear reintroduction programme in the Pyrenees Mountains and while not without its controversies and technical challenges, the numbers are increasing.

The idea of wild brown bears roaming Ireland is thrilling, but once I had set on this ambition I worked backward – how could that actually be achieved?

While Wild Nephin has yet to achieve anything of practical consequence it has established the idea of rewilding and ‘functioning ecosystems’ in official circles.

It would therefore be an obvious place to envisage the reintroduction of bears to Ireland with scope to expand the suitable territory through which bears can move across the landscape – south to the Sheffrey Mountains and through to Connemara in Galway – or north through the Ox Mountains and on to the highlands of Donegal.

A chance encounter in the summer of 2019 went some way to bridging the gulf between the vision I have just laid out and the reality on the ground in this part of Mayo.

I had been invited by the National Gallery of Ireland to contribute to a project exploring landscapes in Irish art. ‘Shaping Ireland’ was an art exhibition which was accompanied by a beautifully produced book reproducing the artworks and interspersed with short essays on environmental issues.

The project challenged people to question what we see when we look at the land and sea around us and to engage in the realities of ecological degradation. I contributed a story about extinction suggesting that as the lights go out our eyes become accustomed to the darkness, so we don’t mourn for the species which are no longer there.

At the exhibition opening there was a dinner for the contributors and I was seated beside the artist Niamh O’Malley. Niamh’s work in the exhibition was entitled Nephin and is a silent, 21 minute 31 second video, filmed from a car as it drives around Nephin Mountain, close to, but not a part of the Wild Nephin wilderness area.

A dark dot on a piece of glass in front of the lens tries to remain fixed on the mountain as the car follows the twists and turns of the road – although sometimes being obscured by hedges, walls or one-off houses, even, at once stage, billowing smoke from a fire.

It’s a meditation on the landscape in which she grew up. I had earlier watched the video in the exhibition space and so we quickly fell into conversation about the meaning of landscape, people’s relationship with it, and the hope for rewilding.

To me, an artist, especially one who has reflected so deeply on their landscape, is better equipped to see the connections that I, as an ecologist, am likely to miss.

Rewilding… but not in the wilderness area

While Niamh moved away from Nephin in the 1990s, as serendipity would have it, she was locked-down in her family home under the mountain during the Coronavirus pandemic when I emailed her in April 2020. “Good timing, Pádraic!” she told to me, after I asked her perspective on the cross-section between wild nature and the fortunes of people in this part of Mayo. This is what she wrote to me in return:

“I’m conscious of the history of this particular landscape in peoples’ imaginations. The west of Ireland has been conjured and described by De Valera, by playwrights, poets and painters. It’s a place which has long functioned in the nation’s imagination as some sort of untouched or true Ireland – which is of course nonsense. I am also so anxious that our small country becomes an exemplar in the climate crisis, that we try to lead in finding new ways of living with the Earth. So, I am already persuaded that much needs to be done and I see the logic of what is happening here but also do not feel it has been adequately communicated – even to those who are predisposed to be fully on board.

“Many of the thoughts here were clarified and extended by a chat with a family friend and local sheep farmer, Sean Syron. I spoke to him about your questions as I knew he would be more informed and also very thoughtful in relation to the project. One of Sean’s comments really struck me, he has a real problem with the term ‘re-wilding’. He wouldn’t have minded ‘wilding’ but did not understand what this could mean, ‘re’ – a return to what and to when? This is a place with evidence of farming going back 5,000 years and we all know Ireland was once covered in deciduous forests. Species such as fuchsia, rhododendron, knotweed, sika deer, New Zealand flatworms etc. are not native – how will they be managed? How does it actually work? There was talk that much of the Coillte land (which forms a large part of the area) would no longer be harvested but harvesting has actually continued.

“A lot of my own thoughts on the reality of how people respond to Wild Nephin, are mired in the economy of the region. There is a culture of supplementing income which has been necessary both because of the quality of some of the land and also the small size of the farms as distributed by the Land Commission. Some examples: in the 1930s the council paid people to cut turf – it became a new way of supplementing survival on poor land. Coillte and Bord na Móna provided seasonal local employment, allowing people to develop and sustain their farms. Many of these industries and successive layers of European and state intervention have shaped how these communities have been advised and allowed to farm and live. Incidentally, animals have almost always been incentivised and crops never. Emigration has also played a part (money sent home or brought home) and nowadays many of those left farming the land have another job which they travel to. Small local schools have closed, there aren’t enough priests for the local churches, people are being forced to travel (drive) more now for these and almost everything. There is no public transport.

“What there is a sense of, I think, is of an outsider/state/Europe that continually changes its mind about what is good for the land, the country, the economy and new rules and subsidies evolve without any real consultation or understanding of the specific nature of the place.

“The people I know see themselves as custodians. They love the land, they know every inch of it. They have cared for it, named it and know the history of its people and mythology. Their ancestors fought for the land. These are all things that also form a landscape.

“My understanding is that people feel there is a lack communication and also that they are not being told the truth. I know some meetings have been held and apparently there was talk of people (tourists?) needing to be able to find somewhere to be alone. Incidentally there was no talk of the scourge of midges from March until September! If the project is, for example, really a carbon storage and biodiversity project, then it should be communicated as such. If it is that, then it also has a quantifiable economic value. If there is a value here then something must be given back.

“The West formed a large part of the nation building of Ireland in the 30s and 40s. I think for many people it still exists as an image rather than a place, an idea of a country, pure and untamed rather than a complicated and layered lived, generational, experience. Personally, I believe those involved in developing these projects must live in the communities and talk to those who have built this landscape thus far.”

There is a lot to consider in what Niamh says. It has convinced me that Wild Nephin has thus far been a failure.

It uses the word ‘wilderness’ in a clumsy way, without acknowledging its historic baggage and perpetuating the idea that it is some kind of resort for people who live elsewhere.

It has demonstrably failed in delivering any meaningful action on the ground but, worse than that, it has failed in even the most superficial way to engage with local people.

In using nature as nothing more than a shiny lure on a tourist brochure it has missed an opportunity to give local people a sense of ownership over the landscape in which they live.

There is no sense that wild nature brings great benefits to people beyond the flow of income that tourists might bring. To me, it doesn’t matter whether you live in the heart of Dublin or the sparsely populated plains of Mayo – if we cannot foster the love that comes with knowing we are a part of nature, then we are failing to address our multiple crises.

—

In 2020 the EU published a Biodiversity Strategy in response to growing concerns over the loss of nature. Among the many ambitious targets were to increase the extent of protected areas for nature to 30% (as I write Ireland has protected around 13%) and 10% should be what they termed ‘strictly protected’.

They didn’t go further in defining what ‘strictly protected’ means but the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, which defines different levels of protected land, says that Category Ia: Strict Nature Reserve is “strictly set aside to protect biodiversity where human visitation, use and impacts are strictly controlled and limited to ensure protection of the conservation values” and among its distinguishing features it should “have a largely complete set of expected native species in ecologically significant densities or be capable of returning them to such densities through natural processes”.

In response, the Irish Natura and Hill Farmers Association published a press statement saying “this designation will sterilise everything making it impossible to secure planning for dwelling houses or any further farm development. New business start-ups in these areas will cease and over time we will see many existing businesses being forced to close. Improvements to our roads and other vital infrastructure will slow down and in time cease and all of this will of course have knock on effects in the provision of essential services and where applied will accelerate a major population decline”. The farming group went on to promise “a major public campaign to ensure this appalling vista does not become a reality”.

I want to stress again that I do not want to see farming or other commercial land uses disappear from places like County Mayo. I would like to see an acceptance that farm animals are not suitable in many areas, particularly peatlands, but that where the land is suitable, and where there are farmers who want to farm, there should be close-to-nature programmes to encourage this. Farming can include not only cattle and sheep but bees, fruit and other horticulture, timber for fuel or other forest products.

I foresee a landscape that has some areas that are strictly protected for nature alongside small, family farms that sell their produce locally; a landscape that is not dependent upon tourism alone for income but which attracts small businesses and people, including families, who are drawn to the idea of living in an area that is rich in nature and community.

The really ‘appalling vista’ is a landscape that is devoid of nature, which has polluted rivers and empty seas; which has no economic opportunities for young people and which year-on-year sees migration to cities, closing schools and depopulation of whole regions. It sounds a lot like what we have right now in many parts of rural Ireland.

What I really want is new relationship with nature.

John Muir, the Scottish-born émigré to the United States, and someone who was key to setting up the much-loved National Park system there, described the feeling best over 100 years ago:

You cannot feel yourself out of doors; plain, sky and mountains ray beauty which you feel. You bathe in these spirit-beams, turning round and round, as if warming at a camp-fire. Presently you lose consciousness of your own separate existence: you blend with the landscape, and become part and parcel of nature.[vi]

Artwork by: Jacek Matsiak

By the time I finish writing it’s July 2020.

The world is in the teeth of a pandemic that has shut down much of society since the middle of March, transforming everything. Airlines have been grounded. For a while traffic came to a halt, restaurants and bars shut, workers were told to stay at home or take emergency wages from the state.

At that time, 1,741 people had died in Ireland from the Covid-19 virus and there had been over 25,000 confirmed infections. Worldwide the death toll was over half a million people.

For much of the time since lockdown started, movement has been restricted. First, it was only within 2km of home, then 5km, then 20km, but at the end of June these restrictions were lifted altogether – so I decided to take a roadtrip.

It had been my intention to do this for the final instalment of this project but in the end I did all of the interviews over the internet.

I nevertheless felt the need to see the land, the sea and the sky of the places I was writing about – as well as perhaps meeting in person some of the people who live there. So I planned a route that took me from Galway into the hills of Connemara and then north to Wild Nephin in Mayo and the boglands beyond.

I started this project in January 2019. Apart from the pandemic, the intervening 18 months have seen fires and deforestation in the Amazon which threaten to tip the rainforest into an entirely new ecological system – collapse, in other words.

The summer in the Southern Hemisphere saw horrific wildfires engulf the south and east of Australia which were estimated to have killed a billion animals, including thousands of koalas, and leaving Sydney in a haze of harmful smoke for weeks.

An epic swarm of locusts has swept in an arc from East Africa, across the Middle East to Pakistan in numbers not seen in decades, threatening food supplies and adding to climate breakdown and violent conflict in some places.

As I did this research, residents of Siberia were experiencing temperatures never before seen, 38 degrees Celsius in one town north of the Arctic Circle, in a warming trend that threatens catastrophic melting of permafrost and release of methane – a potent greenhouse gas.

In 2019, species which went extinct included the Hawaiian snail Achatinella apexfulva, Australia’s Bramble Cay Melomys, Melomys rubicola (a small marsupial), the Malaysian population of Sumatran Rhinoceros and the Chinese Paddlefish, one of the largest freshwater fish in the world and a species that was unique to the Yangtze River.

On-going tropical deforestation, bleaching of coral reefs and fires in biodiversity hotspots like Australia are certainly leading to the extinction of species which have never been documented by scientists.

The Bahama Nuthatch, a bird, is suspected to be extinct as there were only believed to be two remaining individuals before the Category 5 Hurricane Dorian slammed into the Bahamas in September 2019.

And throughout this time the warnings from scientists have continued to mount, including in May 2019 when the UN’s Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services declared that 1 million species would be threatened with extinction over the next 10 years.

The language of these publications has changed.

Previously, scientific authors have been studiously impassionate but they are increasingly abandoning their cold and removed analysis in favour of appeals that ring with urgency and increasing desperation.

In May 2020 one study, published in the journal Nature, made a statistical analysis to conclude that “the probability that our civilisation survives itself is less than 10% in the most optimistic scenario. Calculations show that, maintaining the actual rate of population growth and resource consumption, in particular forest consumption, we have a few decades left before an irreversible collapse of our civilisation” and noting that “the Paris climate agreement is in fact, just the last example of a weak agreement due to its strong subordination to the economic interests of the single individual countries.[vii]“

In April National Geographic published a special edition to mark the 50th Anniversary of Earth Day. The magazine, with its iconic yellow border, was split in two: ‘How we saved the world: an optimist’s guide to Life on Earth in 2070’ showed one headline across our familiar green and blue planet. Flip it over and an alternative headline: ‘How we lost the planet: a pessimist’s guide to Life on Earth in 2070’ was set against a scorched and brown land with the familiar outlines of continents lost under a rising sea.

In January, UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, expressed his concerns for the world in the form of “four horsemen”: the threat of war between large nations, the damage being done to the planet, rising global mistrust including hatred and inequality, and finally, the dark side of digital technology which threatens to invade our privacy and unleash lethal autonomous machines in war[viii].

On the plus side, there is growing awareness across society that environmental issues are increasingly serious and require decisive action. There have been on-going ‘Fridays For Future’ protests and marches by schoolchildren as well as disruptive actions from Extinction Rebellion.

In Ireland’s general election in February 2020, the Green Party won a record 12 Dáil seats while other political parties (although not all) were stepping up with their own policy proposals to address climate breakdown and biodiversity loss.

The European Union promoted its ‘European Green New Deal’ which is accompanied by an ambitious biodiversity strategy and massive investment in decarbonising the economy over the coming decade. A ‘Farm to Fork’ strategy plans to drastically reduce the use of chemicals and increase the amount of organic farming.

As I drove to Galway on my roadtrip a new government had just been formed which includes the Green Party in coalition with the old Civil War rivals Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. The government programme includes many ideas which potentially address the issues I have talked about throughout this project: large and managed marine protected areas, an end to overfishing, nature-friendly forestry, rewetting and rewilding the bogs, subsidies for farmers based on measurable results, removing the hated ‘eligibility’ rule that requires farmers to remove habitats in order to receive payments, as well as significant investment in public transport, renewable energy and retrofitting homes to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions in line with scientific advice. There is increasing acceptance that things must change… but will it be enough?

My journey takes me along the coast road which runs north of Galway Bay. Beyond the town of Barna there are new schools and salubrious new homes with bay windows looking out onto the sea.

There are also the outlines of farmers’ fields, the ones that are hemmed in with ancient stone walls so unique to this region. They are usually lost under an increasingly dense canopy of willow and brambles with drifts of meadowsweet or flag iris.

There’s the odd donkey but mostly there are very few farm animals. The landscape changes abruptly at Ros a Mhíl where small, enclosed fields give way to the open bog. There’s a quarry on one side of the road excavating the land and selling bags of sand. There were at that time prospecting licences being dished out by the government to gold mining companies in this area, something which was rightly vexing local people. Mining would be horrific but the land here is already devastated – damaged peatlands stretch as far as the eye can see.

I spend a day hiking the Twelve Bens, a scenic cluster of peaks and a ‘Special Area of Conservation’ (SAC). But apart from a single raven and a handful of meadow pipits I see no wildlife.

There should be golden eagles and rare mountain plants but instead I see sheep, soil erosion and vegetation nibbled to the root.

News breaks that the European Commission is referring Ireland to the European Court of Justice for failing to implement the Habitats Directive and to take any conservation measures in SACs. I talk briefly to a journalist while on the summit of Bencorr and do my best to describe the scene.

the 12 Bens – scenic but near dead

Later that evening I visit Gerard Walshe, a beef farmer in Moycullen, on the shores of Lough Corrib. His Belted Galloway cattle graze a combination of hazel and ash woodland and open fields filled with orchids, ferns and sedges.

He recently found that he has a population of marsh fritillary butterfly on his farm, a rare species and Ireland’s only protected insect. Gerard is not a fan of rewilding but instead thinks we can have more natural woodland alongside cattle, which are anyway needed to keep the orchids and the flower-rich meadows from being lost under the encroaching brambles and blackthorn. His farm is rich and beautiful and I find it hard to disagree.

A chance invitation on Twitter changed my plans for the next day.

I found myself venturing down a seldom driven road in the far west of Connemara where I met Josh Mathews, his girlfriend Aisling and his brother Duncan. They are all ‘Young Greens’ and were happy to chat about the recent decision by the Green Party to join the government.

They voted in favour of the agreement, but did so reluctantly, they told me. Young people are worried about climate change but they also face impossible rents and increasingly precarious work contracts. Hopes that their parents may have had, like owning a decent home or saving for a pension, seem out of reach to many of them.

Josh, Aisling and Duncan showed me around their farm which they are hoping to develop into native woodland and they enthusiastically tell me about the wildlife that they see – including badgers, pine martens and hares. Another brother is growing veg in a polytunnel as well as rearing pigs and chickens. They have a patch of hill land which is not grazed and it is layered with heather, lichens and mosses which are missing from most of the open bogs in this area. Government subsidies stipulate though, that they must keep a minimum number of sheep in order to claim payments from their land. They’re a nice bunch and I feel better about the world when I leave.

My journey north took me across the border from Galway into Mayo and the desolate Doo Lough valley, with the Sheffry Hills on one side and Mweelrea, at 814m Connacht’s highest peak, on the other.

In May, an article in the Irish Independent, highlighted how there is a “booming trade” for land in this area, “driven by the potential for substantial returns from programmes such as Young Farmers’ Scheme and ANC [Areas of Natural Constraint, another subsidy scheme], as well as the possibility of insulating farmers’ Basic Payment Schemes entitlements”. Farming the subsidies in other words.

Some of the buyers, the article claimed, “have never even seen or walked the land in some instances”. When I tweeted the article at the time, one sheep farmer replied to me that he’d prefer to see the land rewilded.

The vast valleys here are barren. If there are trees they are most likely to be of the non-native coniferous variety. There are tourist signs for cyclists and walkers but I meet none.

I do see some cordoned off areas where native trees have been planted and they seem to be doing well despite the harsh conditions in this part of the world. But it’s a small patch in a vast landscape.

Where the road meets Clew Bay, on the northern shore of this peninsula, I visit the scrap of ancient Atlantic rainforest at Old Head. The weather is foul but the sky clears just long enough for me to snap a photo of the oak boughs leaning out to the sandy beach and the ocean beyond.

The rainforest meets the Atlantic Ocean at Old Head

I round the curve of Clew Bay and its hundreds of islands. I pass under the foot of Croagh Patrick, Mayo’s holy mountain, though not revered enough to save its vegetation from the trample of thousands of pilgrims and the appetites of hungry sheep.

I’m headed to Achill Island where I am meeting someone who has transformed Green politics in the space of only a year. The weather is fierce. The wind buffets the car as I cross the open moors while the rain drives down so heavily that I must slow to a crawl even with the window wipers on full tilt.

At the small village of Dooagh Saoirse McHugh greets me with her partner Colm, her adorable dog Olive and the smell of coffee and fresh-baked cookies. Homely as it is, she tells me that the storms on Achill are getting so fierce that she’s worried about spending another winter in the house.

The storm beach – a ridge of large rocks and boulders shoved inland by the Atlantic Ocean – is approaching. She points out the ruins of a house that was recently swept away. It’s hard to find a place to rent on Achill, she tells me, noting that half the houses on the island are empty holiday homes.

The rain has cleared but the wind is so strong I feel myself planting my feet into the ground to steady myself. Saoirse came very close to winning a seat in the European Parliament in the May 2019 elections.

Never before had a Green Party candidate made a ripple in rural parts of the West of Ireland. Not everyone agreed with her challenge that ‘rural Ireland’ had more to fear from climate change and corporate meat processors than climate action and socially balanced agricultural policies.

Her public defence of plans to accommodate a couple of dozen women asylum seekers on Achill resulted in a backlash from some quarters. But her message of social justice being intrinsic to climate action has resonated, particularly with young people.

She campaigned against the Green Party going into government with the traditional right/centre parties that have dominated Irish politics for a century and which, in her view, represent a perpetuation of the status quo.

“Young people now feel very disillusioned” she tells me. “For the Green Party to be associated with another round of austerity will do lasting damage to the Green movement. Most of the young people I know face a future of low incomes and poor housing. Green policies cannot be stand-alone policies; every policy should have greenery embedded within it.”

Saoirse’s political stand has created tensions within the Green Party, and not long after our conversation she left it. She has been called a ‘Trot’ (Trotskyite) and accused of belonging to the wrong party. But she articulates many of the themes that I have tried to highlight in this project: if we want to save curlews, we must address the corporate-dominated food system; if we want actively managed marine protected areas that work for local island communities, we must address the inequalities in the fishing industry; if we want rewilding of bogs and hillsides, there must be access to warm homes and decent jobs for those living in these areas.

Saoirse brings me to her plot of land where she is growing some veg. She has also left a patch just for nature. She has planted some trees but the wind has stripped them of their leaves – but they’re not dead and any growth will make it easier for the next generation. They’ll get there. She tells me she gets strange comments as to why she won’t put sheep on the field.

Later I check into my B&B in Newport, a picturesque town on the banks of a broad river of the same name. I had planned to use the town as a base for exploring the nearby ‘Wild Nephin’ project, a vast tract of coniferous forestry that has been rebranded as an ‘untamed wilderness’.

Since 2018 it has been incorporated into the adjacent Ballycroy National Park, creating an impressively large expanse of protected land. But just as I set off my car refuses to start. I had ignored the steadily worsening growling from the engine for weeks but now it wasn’t giving an inch. So a local mechanic came to tow it away.

I’m disappointed that I have to abandon my plans, but with the sun shining and feeling the need for some exercise, I start walking out of town. When I get to a sign for ‘Lough Furnace’ I decide to follow it and to my great delight it leads me up a narrow botherín through a patchwork of old oak woodlands, reed-fringed lakes and fields bursting with wild flowers.

This is the road towards the Wild Nephin area but here, outside any designated areas, there are fields that are rewilding with great tufts of ferns and mats of thorny scrub. The dark mountains loom in the distance. It’s rare to see such a landscape with so few buildings or other intrusions of the modern world.

Wild Nephin has benefited from nearly a decade of marketing, using the word ‘wilderness’ to evoke a different type of experience. Before I leave the B&B and take the train back to Dublin, I ask the owner what she thinks of the project and if it does anything for local tourism. She tells me she has never heard of it.

10 days later I’m on the train back to Mayo, this time in the company of my 13-year-old daughter Maia. We packed tents, sleeping bags and enough chocolate and freeze-dried food to keep us alive for two nights and days deep in the ‘wilderness’. It’s drizzly as we pull up to the car park a few hundred metres beyond the wooden roadside sign proclaiming ‘Welcome to Wild Nephin Wilderness Area’.

But it’s not cold and we’re well kitted out as we pull the rucksacks onto our backs. Moments later a truck pulls up with a trailer full of sheep, the farmer gets out and drives the animals over the bridge onto the open land beyond.

Our first night is spent on the banks of a river with towering spruce and cypress trees leaning over the water. It’s dramatic and the air is clear and fresh. After nightfall, with the sound of running water and gentle rain, it doesn’t take me long to fall asleep.

The next day, after a porridge breakfast made with powdered chocolate milk, we pack up and make for the sign-posted ‘Western Way’. The woods near the car park are open and mature, with branches festooned with feathery lichens and damp cushions of moss, but it’s not long before we meet with the bare soil and broken brash associated with clear-felling and industrial forestry operations.

In 2013 we were told it would take 15 years convert all this to ‘naturalised’ woodlands and to clear away the thickets of invasive rhododendron. But seven years in little has happened aside from commercial felling and new squares of commercial planting.

Room for improvement

All the same, the sun is shining and I’m proud of my daughter as she shoulders her heavy backpack for over 10 kilometres and later sets up her own tent. We pitch our tents along a river near the boundary with the open bog and later we hike up to a lake in the valley for a swim.

I can’t help myself as I deliver sermons about peat erosion, greenhouse gas emissions and the impacts of too much grazing on the vegetation. She scolds me for blaming the sheep; it’s people, she reminds me, that decided they should be here.

We flush a covey of red grouse, a trio of females exploding out of the heather. They’re a bird she had never seen before and I’m glad we had at least this wildlife experience to bring away.

Wild Nephin isn’t what it says it is but I promise her that there are people trying to change things. I promise her that her own actions, like striking from school with her friends, or going vegetarian, are making a difference. She promises me that she’ll take me back to Ballycroy in 50 years, when I’m 97 and she’s 63, even if I’ll be in a remotely operated hover craft. We both hope things will be different then.

[i] Taken from Ancient Legends of Ireland by Lady Wilde. 1899. Chatto & Windus

[ii] Hickey K. Wolves in Ireland. 2011. Open Air.

[iii] From Thinking Like a Mountain by Flader S. L. 1974. The University of Wisconsin Press.