The beauty of the world hath made me sad,

This beauty that will pass;

Imagine if all the birds vanished from Ireland. Picture for a moment your daily routine, except with no bird song, no seagulls rummaging around the bins, no rooks descending on freshly tilled fields, no clouds of gannets and fulmars trailing after fishing trawlers.

Imagine they had all simply disappeared.

Many years later, people would reminisce about the size of the seagulls or how the robin would literally stand on the spade handle, watching expectedly for worms while you dug the garden. “Isn’t is an awful shame we don’t have these things anymore” people would say.

And time would pass.

Our lives would likely go on as normal. Birds in Ireland don’t pollinate crops and so their passing would not affect food supplies.

They don’t play any particular role in modern beef or dairy production and are not needed for rearing lamb on hillsides or pigs in factory sheds. In some places there would be more pests but this could be countered by greater application of trapping or chemical repellents. For many, removing a nuisance abundance of crows, pigeons and seagulls would be a great plus.

A burgeoning industry for garden bird food would collapse and summer trips to seabird colonies would dwindle but, by-and-large, this would not precipitate a great employment crisis.

The Wild Atlantic Way would still draw many thousands of visitors to peer at its guano-stained, but now lifeless, cliffs and rocky outcrops. In time, the names of most of the birds that once called Ireland home would be forgotten and only a few would live on in art, poetry or song – like the tiny wren remembered on St. Stephen’s Day in Lá an Dreoilín, where straw-clad marchers traditionally called door to door for offerings.

If noticed at all today, the clicking wren harmlessly flits through briars, but our ancestors didn’t have much time for them.

An old tale tells how:

The wren is mortally hated by the Irish; for on one occasion, when the Irish troops were approaching to attack a portion of Cromwell’s army, the wrens came and perched on the Irish drums, and by their tapping and noise aroused the English soldiers, who fell on the Irish troops and killed them all. So ever since the Irish hunt the wren on St. Stephen’s Day, and teach their children to run it through with thorns and kill it whenever it can be caught. A dead wren was also tied to a pole and carried from house to house by boys, who demanded money; if nothing was given the wren was buried on the doorstep, which was considered a great insult to the family and a degradation.[i]

Although this tradition lives on, the practice of catching and pinning a (sometimes live) wren to the end of a pitch-fork (thankfully) does not survive.

So the parades go on without the need for any actual wrens. We wouldn’t really miss the little birds.

And in our imagined future, like today, few people would recall the cry of the redshank, the sight of a golden eagle darkening the sky or the heart-stopping fright as a red grouse explodes out of the heather at close range.

In fact, we already know what this future looks like.

14 species of bird have gone extinct from Ireland (if you only include those which have not been reintroduced – like the eagles and the red kite – or found their own way back – like the great-spotted woodpecker).

Many of these, like the crane and the bittern, have been gone so long that no living person remembers a time when they were part of our natural fabric.

The corn bunting disappeared in my lifetime (some time in the 1990s) but, being rather inconspicuous, this was scarcely noticed. A further 37 species are on BirdWatch Ireland’s ‘red list’, meaning their populations have ‘declined severely’ since 1800 or where their breeding range has declined by 70% or more over 25 years. At a human level, this means that most of these birds are culturally extinct – in other words, most people are unlikely to ever encounter them over their lifetimes.

And so there is already practically no personal experience surviving of breeding curlews, redshanks or corncrakes, hunting barn owls or soaring golden eagles. Virtually no one has heard a yellowhammer calling from a hedge, with its unmistakable ‘little-bit-of-bread-no-cheese’ song. And as these phenomena pass from human experience, so they pass from our art and heritage.

But there is something clearly at odds with the passing of beauty and song and the story we are told by ecologists that our very existence depends on nature.

Few people doubt this to be true, but how can we then explain why – in Ireland at least – our material lives have never been better while all around us the natural world fades into oblivion?

Were all the birds really to vanish tomorrow, why would it not affect our lives more directly? Yes, we would feel it in our hearts, but if nature is as vital as people say, why would we not then feel it in our stomachs and our pockets as well?

Ecological collapse is normally the stuff of science fiction movies like Blade Runner or dystopian novels like The Road by Cormac McCarthy. The archetypical theme will be familiar to anyone who’s ever seen a zombie movie – a relatable ‘everyman’ character is plunged into a world transformed, where the familiar and comfortable are suddenly the alien and dangerous. In these worlds, from Pixar’s Wall-e to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, the natural world as we know it is gone, dead even.

The opener to Blade Runner 2049, staring Ryan Gosling and Harrison Ford, bases the film’s premise on the “the collapse of ecosystems in the mid-2020s” which gave great power to a single industrialist whose “mastery of synthetic farming averted famine”. Beleaguered citizens scratch out an existence in soulless cities, or, in the case of Wall-e, are morbidly obese imbeciles in flying saucers. Ecological collapse in these worlds is the total annihilation of biological life – with the exception of human beings, of course. And to read the press these days, it’s a world which is coming to place near you, very, very soon.

In 2017 a headline in London’s Independent newspaper screamed: Scientists warn of ‘ecological Armageddon’ after study shows flying insect numbers plummeting 75% and went on to quote the researchers saying “we appear to be making vast tracts of land inhospitable to most forms of life, and are currently on course for ecological Armageddon. If we lose the insects then everything is going to collapse”.

That same year a headline in The Irish Times decried how Intensive farming could cause ‘ecological Armageddon’ if insects are destroyed over an article on continued agricultural intensification and the use of the herbicide Glyphosate.

Meanwhile British naturalist Chris Packham warned in June 2018 that the “UK [was] facing ‘ecological apocalypse’” while in March of that year The Guardian cautioned that “Europe faces ‘biodiversity oblivion’ after collapse in French birds”. This article went on to say that the “authors of [the] report on bird declines say intensive farming and pesticides could turn Europe’s farmland into a desert that ultimately imperils all humans”.

But in many ways this view of ecological collapse is off the mark. Firstly we might imagine that the result of ‘ecological Armageddon’ would be dead landscapes, and yet anyone who routinely has to escort spiders from their bathroom will tell you that life is still very much all around us.

Secondly though, and arguably more worryingly, it is presupposed that the collapse of the living world is still some point away in the future. It isn’t. It may come as a surprise that the world we inhabit – here in Ireland at least – has already experienced a total collapse of ecological systems.

And although this may be hard to fully grasp, it does go a long way in explaining why the vanishing of what’s left of our bird populations would not hurt us in our stomachs or our pockets. To explain why this is so we need first to understand what an ecosystem is and what it means when it collapses.

Photo: Dikaseva on Unsplash. The science fiction version of ecological collapse.

In ancient times plants and animals were considered to be the unique products of a divine creator, each moulded and shaped independently. Right up to the 18th Century, the populations of plants and animals were thought to be regulated by God himself, with just enough hawks to ensure the smaller birds would not be diminished, just enough little fish to keep the big fish sated.

In Western science it would be Alexander von Humboldt, a Prussian adventurer and explorer who, in the early 1800s, was the first to see how everything in nature was intimately connected with everything else.

The study of these infinite connections ultimately became the study of ecology. It would illuminate an understanding of the world as the web of life – with each species only a gossamer thread from every other. And so the concept of the natural world as a system emerged: the ‘eco-system’.

As every living thing is utterly dependent upon its surroundings, not only the living parts of it but also the non-living air, water, soil and climate, the ecosystem is defined in space. This means that when we talk about an ecosystem we really must set out where its boundaries lie.

It could be the vast oceans – effectively a single ecosystem broken up by smaller patches of land – or the enormous rain forest of the Amazon in South America. Or it could be the ecosystem inside our gut; inhabited by thousands of species of bacteria which are essential for our health and well-being.

A typical back garden or a farm is an ecosystem and each of these examples shares the common features that they are physically contained and consist of a variety of living organisms interacting with each other and the non-living elements around them. In the same way it can be argued that there are infinite ecosystems, there are also ecosystems within ecosystems, or just one giant global ecosystem which connects all living things, including every person and the junk which has piled up around us.

The way in which ecosystems work is far from clearly understood; even in the smallest of ecosystems – a corner of your garden for instance – there are uncountable organisms, from protozoans, bacteria, fungi and larger invertebrates like worms, beetles and springtails. And that’s before we even look at what’s happening above ground!

A good analogy for explaining this, and one which extends to how it affects us as humans, is that of the car.

Imagine for a moment that you are the proud owner of a brand spanking new Tesla Model S. It’s a beautiful piece of engineering which combines cutting-edge technology with lusty design and a price tag to match.

The concept of a car as a mode of transportation doesn’t do the Model S justice. Among its many features are ‘adaptive lighting’ which lean into your bend – perfect for night-time driving on a windy road.

The Model S also comes with something called ‘bio-weapon defence mode’ which, according to the website “removes at least 99.97% of particulate exhaust pollution and effectively all allergens, bacteria and other contaminants from cabin air. The bioweapon defence mode creates positive pressure inside the cabin to protect occupants.”

I could list the full inventory of special features from safety, entertainment, navigation and comfort that no doubt make the vehicle a pleasure to drive. Lest we overlook it, the Tesla Model S is a status symbol, letting everyone know what you think of yourself and where you see your standing in the world.

The most pristine ecosystems, such as a perfectly intact forest, work in much the same way. Their beauty is instantly apparent, but it has taken an awful lot of time in development to get it that way.

All of the various components of the car are equivalent to the species in an ecosystem. Our eyes are only capable of seeing the large, obvious, flashy bits on the outside (mostly the trees in this case) but thousands of tiny working parts, the great majority of the total, are largely hidden from view. We have no idea how these work or how they’re assembled but when they all come together the system hums along.

A pristine ecosystem is remarkably stable; many of the tropical rain forests have stood for millions of years without changing their basic form. Like the Model S, our pristine ecosystem includes a lot of features. From a human perspective, some of these are essential, like food, shelter and clean water. But to stop there would be to see the Tesla as merely a mode of transportation.

The pristine forest also provides fuel, medicine, pets and beasts of labour, a great variety of materials (for clothing, cooking, building and creating), amenity, spiritual sustenance, art (both as inspiration and the means to create it), recreational drugs (including alcohol and hallucinogens) and great variety in diet, something which results in culinary culture and so is much more than just nutritional sustenance).

At a larger scale, the forest helps to regulate the global climate system as well as hydrological and nutrient cycles all of which make Earth habitable for us in the first place. The Amazon rainforest, for instance, is so big that it underpins the water supply to virtually the whole of South America and plays a significant role in global climate patterns due to the amount of carbon it stores.

Imagine – the loss of this single forest expanse that underpins human welfare would have global, and frightening, ramifications. The great stability of the pristine ecosystem meant that people living in it were protected from one year to the next from extremes of drought or flood. Indeed for the great majority of human existence (i.e. the pre-agricultural bit) humans lived within these ecosystems and all of their needs were provided for (including status symbols like the feathers of flamboyant birds for head-dresses or the shells of sea creatures).

The collapse of the Amazon ecosystem is a very real possibility

This is not to argue that early humans didn’t impact negatively on their environment as it is pretty certain that people were responsible for the mass extinctions of large mammals in the Americas and Australia. Nor does it mean that ecosystems never changed – they did, and sometimes quite abruptly – but the likelihood of these changes being catastrophic are much lessened when all the species are intact (and as I’ve already mentioned, many of the great rainforests have survived, largely unaltered, for many millions of years).

For most of us the Tesla Model S will be above our price range, so let’s say we opt for a Nissan Leaf instead. It also acts as a mode of transportation, with many of the features of the more luxurious Tesla so that it too will hum along nicely even without the adaptive lighting or bio-weapon defences.

In our analogy this would be an ecosystem that doesn’t have all the great features of the ancient, pristine forest, perhaps a dryland or a mountainous area which has a lower abundance of food or harsher living conditions. Not all ecosystems are going to provide the same range of services that us humans find valuable.

Nevertheless, they retain their essential function and stability.

There are no ecosystems in Ireland which fall into either of the above categories and it is a long time since we had anything approaching a pristine or totally natural ecosystem on our island.

Now imagine you’re a first-time car buyer and all you can afford is the clapped-out banger a friend of a friend will give you for €300, no questions asked. You soon discover the radio is bust, the heating doesn’t work and the last time the de-mister on the back window actually cleared the fog Bertie Ahern was in power.

You don’t get too upset about these things because you’re proud of your new purchase and it gets you from A to B, and after all that’s all you really care about. This is what happens when we start taking species out of an ecosystem. It may look the same on the outside, but it stops doing a lot of what it may have done before. Maybe the seas are not so rich in fish or the big trees are gone so that a valuable building material is no longer available.

Although the loss of species may be imperceptible to us, and the disappearance of many species goes largely unnoticed by the great majority of us, the system it leaves behind is irreparably weaker and more vulnerable to further changes.

When people in Ireland started to clear the forest to create farmland it resulted in a dramatic transformation from ancient woodland to open grassland. There were species which couldn’t cope with this change and went extinct (for instance the wood lark, the lynx and species of beetle which depend upon large quantities of dead and rotting wood); there were species which managed to adapt to the new landscape and even thrive (such as badgers, blackbirds and many wildflowers and their pollinators which were drawn to the light-filled spaces and pastures grazed by farm animals); and there were some which had never survived in a woodland but which found that agricultural systems provided the open grassland they preferred (such as skylarks, barn owls and corncrakes).

The pre-industrial farmland continued to provide food (albeit significantly lower in variety), clean water, jobs and cultural sustenance.

A system emerged which today would be referred to as ‘agro-forestry’ or ‘sylvopasture’ where the planting of trees helped to protect soil, define field boundaries, keep herds apart and improve animal health by providing shelter from cold winds or strong sun. These hedgerows needed to be maintained and cut back periodically, thereby providing a source of forage for the animals, fuel and timber for a variety of needs, as well as apples, hazelnuts, berries from rosehips, sloes and hawthorns.

Skins and wool from animals provided clothing. Farming dramatically changed the social structure of communities and is widely believed to have greatly accelerated the rise of powerful elites and economic inequality (something which plagues farming to this day). In short, the new agricultural ecosystem continued to provide a lot of what the forest had done but it fell short in some important areas.

Now imagine you’ve arrived from outer space and you’ve never seen a car before. I show you an engine and ask you to explain what it is for. You turn it over and you can see it has pistons, spark plugs, crank shafts and connecting rods and you may hazard a guess that it was used to power a great machine. But you’d be hard pressed to imagine that it took a family of four great distances in style and comfort.

This is the dilemma that many ecologists face in Ireland today when standing in a field or on a hill or gazing through murky water on a deep-sea dive. We see species – evidently these landscapes are not dead.

But so many of the species are missing, there are alien species which were never there before people introduced them, and so many of our plants and animals only exist in much smaller (or sometimes bigger) populations then they once did. Standing gazing at a spark plug, it is impossible to conceive of a Tesla Model S or even a Nissan Leaf. We see green fields, brown hills and the grey surface of the sea but we have no idea how these spaces once teemed with life in all its wondrous diversity.

The ecosystems which once existed have all collapsed.

It was once a BMW

Comparing nature to a car is useful, but as a metaphor it falls short. Machines built by humans can be taken apart and put back together again. Although they are complicated, all machines are understood by people because they were created by them.

Nature, on the other hand, is beyond our comprehension.

Science only gives us a glimpse of how its component parts interact with one another.

Ecosystems, once damaged beyond a certain point, cannot be put back together again. Cars, even the Tesla, inevitably deteriorate and break down. Nature, however, perpetuates and renews itself through eons of time with each component dependent upon the system, and the system depending upon its components – the species. As Jeremy Lent says in his fantastic book, The Patterning Instinct: complex systems, such as a living being, a brain or an ecosystem “arises from a large number of nonlinear relationships between its components with feedback loops that can never be precisely described”[ii].

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has stated that ecosystem collapse “involves a transformation of identity, loss of defining features, and/or replacement by a novel ecosystem. It occurs when all ecosystem occurrences (i.e. patches) lose defining biotic or abiotic [that is, living or non-living] features and characteristic native biota [species] are no longer sustained.”

This definition can apply to all areas of Ireland.

Our seas have been overfished and trawled to oblivion, the land has been so deforested that only about 1% of the surface consists of native woodland while of the midlands’ ‘raised bogs’ at most only 0.6% remains intact.

In upland and mountain regions only 28% of the peatland and heath habitats are ‘worthy of conservation’ and even these have been routinely burned, overgrazed and drained, leaving nearly all of their characteristic bird species threated with extinction.

Our rivers meanwhile are mostly polluted, dams block the migration paths of fish and 11,500km are subjected to routine arterial drainage schemes which have drastically altered the natural flow patterns of the water.

Even the farmland, which was until relatively recently a benign landscape for nature, has been transformed through the use of industrial chemicals and fertilisers and neglect of the ancient hedgerow network.

All of the natural systems we see around us have suffered a ‘transformation of identity’ and a ‘loss of defining features’.

Collapse has been devastating for many of the wild plants and animals which live in Ireland. At least 120 have gone extinct (although a handful of these have returned) and up to a third of those remaining are threatened with extinction or are what the IUCN refers to as ‘near threatened’.

The family of fish comprising sharks and rays has fared worst, with over two thirds of all species in Irish waters falling into these categories. The latest assessment of mammals shows only one species threatened with extinction (the black rat, which was never native anyway) but this rosy view masks the fact that seven species (nearly a quarter of the current total) are already extinct: the right whale, grey whale, brown bear, lynx, wild cat, wild boar and the wolf. But what has collapse meant for people?

Today in Ireland we can no longer rely upon nature for clean water and we depend entirely on machines and chemical processes so that the water from our taps is drinkable.

During the Covid-19 crisis we have been forced to stay within 5km of our homes and many have found that the nature we need for our physical and metal heath just isn’t there – or we don’t have access to it.

Modern Irish farmland continues to produce food, particularly beef, lamb and dairy products, but much of the food we produce is also used solely to feed these animals and very little is made up of vegetables or grains destined for human consumption. A report from the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Agency showed that since 2000 Ireland has been a net importer of food energy, as is the European Union as a whole.

Agriculture is the biggest source of water pollution and greenhouse gas emissions and, according to the National Parks and Wildlife Service, is the greatest driver of extinction in Ireland. So the long list of benefits which were once provided by the pre-industrial farming ecosystem has dwindled drastically.

As well as directly effecting the environment, this transformation has seriously impacted on farmers themselves. Although the Irish Food and Drinks industry returns enormous profits, and according to the state marketing agency, An Bord Bia, has recorded export growth of a massive 60% between 2010 and 2017, this has not benefited most farmers. Indeed the number of people working in agriculture has fallen by about 20% since the late 1990s while all farmers depend heavily on state subsidies to make a living.

In 2019, nearly half of farmers earned less than €10,000 – far below the minimum wage.

And it’s not only farmers.

The coastal fishing fleet has suffered dramatic declines in catches with the great majority of small boats relying heavily on crabs and lobsters which are destined for diners in fine restaurants.

And so the marine ecosystem barely provides employment in these areas, scarcely produces nutrition (in terms of the quantity of calories in the catch) and has left sea life in such a poor state that even many anglers and scuba divers are losing interest in practicing their pastime.

And with the tangible benefits go all of the intangible aspects which we once derived from nature – the culture, the language, amenity, art and spiritual connections which is what has made Ireland unique.

Ecological collapse has directly affected many Irish communities and yet it may feel to many people that this has not affected our way of life. Indeed, Irish people today enjoy a high standard of living in comparison to practically everywhere else – how can this be when the biodiversity we’re told is vital to our survival has been left in ruin?

The answer lies in our consumption patterns. Everything we eat, from a bar of chocolate to a take-away curry contains ingredients from the four corners of the Earth. Even products we could safely assume are Irish are nothing of the sort. Irish beef relies heavily on imported cattle feed including soy beans from deforested land in Brazil and palm oil-derived milk replacers which are fed to calves after they’ve been separated from their mothers.

So-called ‘organic’ Irish salmon are fed fish meal which is the ground-up marine life from who-knows-where. The non-edible consumer goods which clog our homes may have been sourced from mines in dozens of countries while our entire economy is predominantly fuelled from imported fossil fuels.

This includes 90% of our coal, which originates in Colombia, two thirds of which is linked to the Cerrejón open cast mine. In 2018, this mine was subject to a complaint from four development agencies, including Trócaire and Friends of the Earth, to the Irish government calling on it to cut ties with the mine due to allegations of human rights abuses, displacement of indigenous peoples and environmental destruction.

In late 2019 the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination added their voice to stop buying this coal, citing a “serious abuse of human rights particularly affecting people of African descent and indigenous peoples”.

At the height of the economic boom in the mid-2000s, Ireland was 10th in the world for the size of our ecological footprint. This fell back following the subsequent crash, but since then we’ve had another boom and another, pandemic induced bust, but our footprint continues to be way above the majority of countries.

The latest data shows that our ‘overshoot day’ – that is the day of the year when we have used up resources at a rate that can replenished by the planet – is April 27th – meaning that after that date we are using resources which are not being replenished. This represents 35th place in the countries examined. And so Ireland races ahead on the motorway of human development which is wreaking ecological havoc the world over.

Since our own ecosystems have collapsed, our consumption patterns can only be sustained by exporting collapse to other countries. And by the rationale which we have followed so far, if the global ecosystem collapses then we really do put our supplies of food, clean water and the myriad other benefits healthy ecosystems bring to humanity in dire peril.

So, contrary to the dystopian views of science fiction, this world is not dead – it is merely transformed into one which is unrecognisable from what existed only a few centuries ago. This will indeed be apocalyptic for many of Earth’s inhabitants and in this sense there have been some illuminating studies as to just where the boundaries of this doomsday scenario lie.

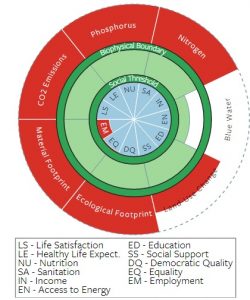

The Stockholm Resilience Institute has identified nine planetary boundaries: stratospheric ozone depletion; loss of biosphere integrity (i.e. biodiversity loss and extinction), chemical pollution, climate change, ocean acidification, freshwater consumption, land system change, nitrogen and phosphorous flows to the biosphere and oceans, and atmospheric aerosol loading.

The researchers highlighted three of these: climate change, biodiversity loss and nutrient cycles where the outer limits have already been exceeded. At the university of Leeds in the UK, researchers there have attempted to adapt these indicators to the level of individual countries, measuring and ranking nations against their CO2 emissions, phosphorous, nitrogen, blue water, ecological footprint, material footprint and land use change.

Ireland’s report card shows that we are exceeding six out of the seven boundaries, with only ‘blue water’ within our allocated limit.

Ireland report card: could try harder

The global situation currently looks bleak. The Stockholm Resilience Centre published further research in 2018 which analysed the current trajectory of these life-supporting Earth systems and found that “social and technological trends and decisions occurring over the next decade or two could significantly influence the trajectory of the Earth System for tens to hundreds of thousands of years and potentially lead to conditions that resemble planetary states that were last seen several millions of years ago”.

They called this the Hothouse Earth – a new state that would be irreversible and would clearly have catastrophic effects for humanity and all other life on Earth.

It’s terrifying, but to be gripped with fear would be the wrong response. The authors point out that we still have an opportunity to act through “collective human action”. “Such action entails stewardship of the entire Earth System – biosphere, carbon sinks, behavioural changes, technological innovations, new governance arrangements, and transformed social values”. Meaning – we need to change everything.

So Ireland is knee-deep in the climate and extinction crises and there is ample evidence that for all the wonderful benefits of modern consumer culture we are, in fact, up to our neck in ecological debt.

Ireland, of course, is not alone in this mess. The University of Leeds team found only 16 countries which were operating fully within their bio-physical boundaries (among them, Sri Lanka, Guatemala and Nepal). This means we can learn from others who are already living within their ecological boundaries.

It also means we have time (albeit not much) to harness our own unique creativity and resolve to create a better world – better cities, more secure communities, resilient farmers and fishers, inspiring landscapes. We’re going to need it all – not just science, money and policy, but art, folklore, faith (if you have one), spirituality, music and song and a restoration of a sense of wonder, joy and connectedness in nature.

In 2017 my book Whittled Away charted just how much of our nature has vanished. In Shaping New Mountains, I want to imagine what a nature-filled Ireland would look like, and how we might get there.

In Whittled Away I mentioned many of the solutions which have been tried and tested both in Ireland and elsewhere and pleaded for greater political prioritisation for nature conservation. I still firmly believe that bringing nature back would be of huge benefit to people, particularly local people, whether your locality is a city, the countryside or by the sea.

But I’d be lying if I said I was optimistic. So far there is little indication that the biggest political parties understand the extinction crisis or feel compelled to act.

Although 2019, when I started working on this project, was remarkable for the level of media and public attention given to climate change and plastic waste, there are still depressingly few who see the bigger picture or are willing to talk about habitat loss, pollution and overhunting – still the main pressures on nature in Ireland. And as I learn more about climate change and how it’s rearranging the furniture of our surroundings before our eyes, I feel less confident that some of the solutions I proposed in Whittled Away, such as marine protected areas or rewilding, can actually be successful in the way I first thought.

But don’t confuse my lack of optimism with fatalism. I am still convinced that, no matter how small the window of opportunity shrinks, no matter how heavily the odds seem to be stacked against the likelihood that we’ll see radical change, the battle will still be worth it. I’m up for the fight – and I hope you will be too.

In Episode 2 of Shaping New Mountains I try to get to the heart of the matter and in doing so try to explode a few myths – are rich countries like Ireland really more advanced than poor ones in their protection of the environment?

Is nature conservation too expensive?

Do environmentalists in Ireland want to turn the countryside into a theme park resembling Jurassic Park?

Can we rely on technology to figure things out?

That’s in the next chapter of Shaping New Mountains.

[i] Lady Wilde. 1899. Ancient Legends of Ireland. Chatto & Windus, London.

[ii] Lent J. 2017. The Patterning Instinct. Prometheus Books.