“In recent years land drainage policy has received attention on two counts: the adequacy of the financial returns to investment of public funds in drainage has been questioned, and it has been alleged that adverse impacts on the environment also result therefrom”.

It might have been written yesterday but these lines are the opener to a review of land drainage policy written by Richard Bruton (now a Fine Gael TD but then a research officer with the Economic and Social Research Institute – ESRI) and Frank Convery in 1982 – nearly 40 years ago.

In fact, land drainage works had been going on since Famine times, when the starving poor were forced to work for relief and bureaucrats dreamt up infrastructure projects in the hope of boosting the economy. This was all achieved with manual labour and subsequent decades of depopulation resulted in ‘neglect’ of the rivers which simply went back about their business.

By the 1930s a new impetus emerged with the availability of heavy machinery while the war years saw famine and food shortages throughout Europe, in turn increasing demand on productive farmland.

The problem, the ESRI noted, was not an excess of rainfall but the saucer shape of Ireland: “as a result, the rivers flow slowly through poor channels. Much of the land suffers from periodic or prolonged flood damage. Even at low-flow, the rivers provide poor outfalls that prevent adjoining lands being properly drained”.

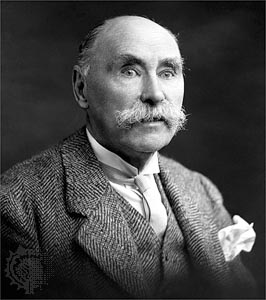

The result was the Arterial Drainage Act, signed into office by the nation’s first president Douglas Hyde on the 1st of March 1945, since when it has remained unchanged.

Ireland’s 1st president, Douglas Hyde, signed the Arterial Drainage Act into law

The ‘drainage problem’ was two-fold. Field drainage was a job for individual landowners while arterial drainage was the widening, deepening and straightening of the main river channels. One was necessary for the success of the other.

The River Brosna, a tributary of the Shannon, was the first to get a going over in the late 1940s with many more to follow in subsequent decades right up to the early 2000s, among them the Corrib, Boyne, Inny and Blackwater in Co. Monaghan. There were many more minor schemes as well as embankments of tidal rivers such as those at the mouth of the Rivers Shannon and Fergus in Co. Clare.

Environmental concerns were raised almost immediately although the Commissioners of Public Works, later the Office of Public Works (OPW), were exempt from the Fisheries Acts at the time and for many years, when the bulk of the works were undertaken, were exempt from any form of environmental impact assessment (EIA). The late-ecologist Oscar Merne, warned that drainage of turloughs was threatening the last holdouts of black-necked grebes – a bird that was last confirmed nesting in Ireland in 2011.

The OPW ‘maintain’ 11,500km of rivers (the blue lines)

A report of the Inland Fisheries Commission in 1975 noted complaints from anglers that:

“Drainage operations eliminated desirable natural meanders in rivers, removed holding pools, destroyed spawning beds, and produced canal-type water courses characterised by long stretches of steep banks piled high with rubble and spoil.”

It bemoaned the lack of research being carried out on the impact of these works, to salmon and trout in particular, although what work had been done suggested that long term damage to salmon numbers was limited. What I have never seen is a study which has assessed the impact of drainage on the ecology of an entire river system. Even today, when some form of EIA is produced, the baseline is the already-drained channel.

The Commission report noted the obligation under the Arterial Drainage Act to undertake continual maintenance of drainage river channels. It noted that “the impact on fisheries of recurring drainage maintenance work gives cause for anxiety”.

These days the OPW notes that Under Section 37 of the Arterial Drainage Act 1945, it is “statutorily obliged to maintain all rivers, embankments and urban flood defences on which it has executed works since the 1945 Act in “proper repair and effective condition”.”

And so, entirely at the public expense, the OPW must, by law, periodically go back to the 11,500km of rivers to keep them “in a condition that ensures they are freeflowing, thus reducing flood risk and providing adequate outfall for land drainage”.

This means that, for no other reason than statutory obligation, the OPW sends in the heavy machinery, tearing out bankside trees and vegetation, destroying fish spawning beds and generally keeping rivers in a canal-like state.

The OPW is not above the law, but in practice you wouldn’t believe this.

It schedules and designs its own works, writes its own impact assessment reports, gives itself permission to fire on and, when things go wrong, reviews themselves and implements their own corrective actions.

To get access to reports, such ‘appropriate assessment’ decisions and supporting reports, we need to go via Freedom of Information. In 2018, we found that the OPW destroyed a kilometre of the Newport River, in Co. Tipperary, a part of the Lower River Shannon Special Area of Conservation, and faced no sanction whatever.

In 2018 the OPW destroyed 1km of Special Area of Conservation and faced no sanction

The result is a state agency fixated on heavy engineering, operating outside the law with no oversight and working to legislation that was enacted at the same time Russian troops were marching on Berlin.

Today our rivers are in a sorry state. Over half are polluted while large dams and other obstructions means migratory fish like eels, salmon and sea lamprey face extinction. But the arterial drainage programme has torn the heart out of rivers by undermining their basic ecological function.

Rivers are meant to meander and flood, it is how nature has adapted to variations in climate and topography. The dynamic essence of a natural river system creates a vast array of habitats not only for fish but birds, trees and other plants, mammals and invertebrates.

Humans are not outside this system – most of our big towns and cities rely on our rivers for drinking water. After spending millions of euro on destroying the river ecosystem we then have to invest more millions in removing silt and harmful bacteria to make the water drinkable.

The IWT has started a petition to urge Patrick O’Donovan, the minister in charge of the OPW, to reform the Arterial Drainage Act. We want a new piece of legislation that works for people and nature, one that is fit for the biodiversity and climate emergency.

Flooding remains a severe, and growing, threat due to climate breakdown but we must focus our efforts on protecting homes and businesses, not farmland.

Indeed, the herculean effort that is made to keep water off farmland means it is adding to flooding risk in towns and cities downstream.

The OPW should be obliged to implement nature-based solutions and should be strictly restricting heaving engineering works where no other options are available. We can pay farmers for storing the water, preferably through restoring and rewilding of river flood plains.

The OPW must be more transparent in their approach and it should go without saying that they need to comply with the law. The National Parks and Wildlife Service or the Environmental Protection Agency should be given the power of authority to licence works carried out by the OPW and given power of investigation and sanction when standards are not met.

If you agree, please sign the petition: Reform the Arterial Drainage Act | Uplift