… as he waded slowly up its course, he wondered at the endless drift of seaweed. Emerald and black and russet and olive, it moved beneath the current, swaying and turning. The water of the rivulet was dark with endless drift and mirrored the high-drifting clouds. The clouds were drifting above him silently and silently the seatangle was drifting below him and the grey warm air was still and a new wild life was singing in his veins

Surely, it’s not fair. There’s something unjust about the idea of creating large, wild areas in rural locations far from the main towns and cities. Why should these lucky few people get to enjoy such wonderful treats while the majority of the population stares at concrete and whose idea of rewilding is cutting the grass once a month instead of once a fortnight?

Why should rural communities get all the attention when the majority of the population (63% of Ireland’s population lives in towns or cities) live nature-depleted lives, commuting long distances in smoggy, congested streets, never hoping for a chance encounter with anything wilder than a blue tit?

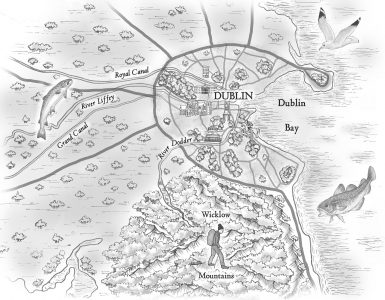

So much water… so much space… so much potential for nature. Artwork by: Naomi McBride

I live on the edge of Dublin City. I’ve always felt Dublin wasn’t bad in terms of access to green spaces. The Phoenix Park was a childhood playground and I remember spending summer days catching eels in its streams or exploring the wilder parts of the Furry Glen where I could catch a glimpse of jays.

More often I’d hear their expletives, a cry that lends the jay its name in Irish: an scréachóg choille or the ‘woodland screecher’. Many Dubliners live close to one of the canals, one for each side of the city, and each are ribbons of greenery pouring nature into the heart of the city. Yes, there are the swans and ducks, but there are also otters and kingfishers while it’s possible to fish for roach and even pike in their (relatively) clean waters.

Dublin is one of the few capital cities with a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve on its doorstep – Dublin Bay – including the unique Bull Island Nature Reserve with its throngs of wetland birds, seals and unique plant life.

There are the rocky outcrops on Howth Head and Killiney Hill, with fragments of oak forest and holdouts for red squirrels. And Dublin is a maritime city. A short boat trip from the harbour town of Howth will bring you to Ireland’s Eye with its puffins, peregrine falcons and swirling colony of gannets.

Even on O’Connell Bridge, in the heart of the city, people can enjoy feeding the herring gulls and black-backed gulls. Yes, gulls are popular with headline writers who like to portray them as marauding adolescents but for many city-dwellers they are the only contact with nature they have – and many love their company. Although not tame, in the city you can get close enough to them to appreciate their impressive size and their handsome plumage.

Further out on the bay, near the iconic Poolbeg chimneys, BirdWatch Ireland and Dublin Port have set up nesting pontoons for Arctic terns, an elegant seabird which undergoes epic migrations from the Arctic in the north all the way to the Antarctic in the south. They’re easy to spot from the ferry on the way to Holyhead or from the walkway out to the Poolbeg lighthouse.

Bull Island has every legal protection for nature on the books.

Whole books have been written about the wildlife of Dublin and material is not hard to find. But here is a question – does nature survive in Dublin despite our best efforts or because of them?

Do we welcome wildlife to our uniquely human environment or are we merely grudgingly impressed that some species have managed to survive – even thrive – in a world we have created exclusively for our own needs.

Bull Island, after all, didn’t exist until the construction of the Bull Wall in the 1820s and was the entirely unintended consequence of shifting tidal currents and patterns of sediment deposition. Today the island enjoys nearly every legal protection we have on the books and yet those who know it best bemoan the unbridled amenity uses which include golfing on the sand dunes, kayaking and paddle-boarding among roosting seabirds, quad bikes on the salt marshes and free-running dogs (despite bye-laws stipulating that dogs should be on a leash). Three species have gone extinct in recent years: the hare and nesting little tern and ringed plover[i]. A new visitor centre is planned which is designed to bring more people to the already heavily-used island. During the Coronavirus lockdown in early 2020, the ringed plover was reported to have returned to its historic nesting sites, but without greater control of disturbance, this effect is not likely to be repeated in 2021.

The coastal promontories at Howth and Bray, despite being ‘protected areas’, are nearly annually burnt to the soil as a result of carelessness or downright vandalism. Dublin Bay, once home to oyster reefs and vibrant marine life, is now virtually devoid of fish while the under-treated effluent of two million people discharges to a chronically polluted estuary. Over-flows and ‘accidental releases’ of raw sewage can make the Bay’s beaches unswimmable.

Dublin sits at the foot of the largest expanse of uplands in Ireland, stretching from Tallaght and Sandyford in the southern suburbs all the way to Carlow and Wexford and yet the vast bulk of this is made up of nature-free conifer plantations or sheep ranches. Even the Phoenix Park is dominated by non-native trees and vast expanses of species-poor grasslands.

Dubliners are rightly proud of the Park and are quick to tell visitors that it’s the largest enclosed urban park in Europe. At a shade over 7km2 it’s certainly big – five times that of London’s Hyde Park and twice that of New York’s Central Park. I can also attest that despite the crowds at the zoo, the throngs which descend for music concerts or the annual ‘Bloom in the Park’ trade fair, it is easy to find a quiet spot to lie in the grass on a summer’s day. The eels are gone but it’s still possible to hear the jay screeching in stands of old oaks.

No, we don’t really make an effort to make our city wildlife friendly. There’s a considerable body of evidence about how green spaces are good for our mental health, how they’re great at cleaning city air, cooling buildings in summer and sheltering them from cold winds in winter. Yet we don’t really see the potential and we have yet to see these green spaces as essential infrastructure, just as important as the sewers, the electricity ducts or the roads.

—

Seventeen times bigger than the Phoenix Park is Rio de Janeiro’s Pedra Branca State Park which harbours a chunk of Atlantic Rainforest, a biodiversity ‘hotspot’ with 338 species of bird and 51 species of mammal. According to Wikipedia it has 40 park rangers and Brazil’s first environmental police unit.

Twelve and a half times bigger than the Phoenix Park is Sanjay Gandhi National Park in Mumbai, India. The park is home to a small population of leopards which are known to make forays outside the confines of the park into the city streets themselves. Scary? A 2018 study found that the leopards were helping to control the city’s population of rabid wild dogs, saving the local authority money and possibly saving up to 90 lives a year[ii].

Even in Europe, the expansive Bymarka, on the edge of Trondheim in Norway extends over 80km2 (eleven and a half times the size of the Phoenix Park). It is a swathe of pine and fir forest with lakes, bogs and swamps as well as good numbers of moose, beaver, roe deer and even what is believed to be Norway’s oldest wolverine (at 18 years old). Bymarka is a place I know well as it’s the home of my in-laws and a place I have being visiting for over 20 years.

In winter the people of Trondheim ski along its snowy tracks, some of which are even gently lit at night. In summer there’s swimming in the lakes while autumn is a time for picking mushrooms and blueberries. Good public transport and a network of hiking trails make the forest accessible to all. So accessible in fact, that many ‘forest kindergardens’ operate in it. Children here spend nearly all of their day in the forest.

There is no commercial extraction of timber and so the place feels wild and natural, even if its bears and wolves are still missing. The ‘town’s forest’ (as Bymarka translates from Norwegian) is less than half the size of the Wicklow Mountains National Park. Yet, unlike the Wicklow Mountains, it is full of nature.

What if we stopped looking at Dublin as a place exclusively for people, letting some nature creep in under the door; but instead flung the gates open wide to bring wild nature right into our streets and parks?

—

The mountains south of Dublin currently don’t have much nature in them. Rewilding could change that.

There’s a point along the path leading through Ticknock Forest Park, just five minutes from Dublin’s perpetually congested M50 motorway, that commands a sweeping view of the capital. Late on a summer’s evening in July 2019 the air is damp from a recent downpour but the light is soft on the buildings in the city centre, casting a glancing glow on the silvery bay and the hill of Howth far to the north.

It is my first time to visit Ticknock, one of a series of commercial forestry plantations strung along the low hills south of the city, but I am here on this evening to meet with Ciaran Fallon, who is the director of Coillte Nature, the state forestry company and the country’s largest landowner. Ciaran was a Green Party councillor from 2004 to 2008 but later moved to Coillte as Director of Stewardship in 2012.

He is in affable humour when we meet and why wouldn’t he be? His employer has recently announced the creation of a new unit within the company to be known as Coillte Nature. It may end up like a bad bank for commercial forestry, a NAMA for trees if you will, where poorly performing plantations can find a home without bringing down the books. It makes perfect sense, about one third of Coillte’s plantations have little or no commercial value, with many of these in areas with high scenic, amenity and wildlife potential.

In 2017 Ticknock, along with a number of other plantations in the Dublin foothills which are profitable from a timber perspective, were due to be clear-felled. But opposition from the Green Party and amenity interest groups managed to halt the plans. Coillte Nature has now developed a vision to convert all of these areas into native woodlands.

“It’s incredibly exciting” Ciaran enthuses, “we’ve only ever thought of these places as commercial entities, the only value we’ve put on them is in the timber when it is all clear-felled away. But over 200,000 people come to this place every year to enjoy the outdoors, the value of that never appeared on our books”.

The opposition to clear-felling back in 2017 forced a rethink. “Now we can imagine transforming all of these plantations into permanent broadleaved woodlands, it’s going to be a stunning amenity for Dubliners in the decades ahead”.

Indeed, the popularity of the area is testament to people’s pent-up longing for contact with nature. The 200,000 people who visit Ticknock do not get to see much nature – nearly all of the trees are homogenous blocks of dark conifers – but for now this will just have to do. It is a plywood imitation replica of nature but one which nevertheless provides relief from the angular tedium of the suburbs. But now we have a new vision – one which finally recognises that an immense native woodland on the doorstep of over 1 million people will be of considerably more value than clear-felled pulp.

We look down over the city – the expanse of the Phoenix Park can be seen to west, the Liffey behind its quay walls winding its way to the Bay and the North Bull island spreading north of its mother wall.

“The landscapes are always changing, everything we’re looking at is in a state of flux. In 50 years’ time we could come back and who knows what it will be like? If we don’t tackle climate change then much of the coast may even be surrendered to the sea. Coillte were the first to bring trees to the Dublin Mountains back in the 1950s – before that, it had been centuries, maybe millennia before there were forests here. Now we’re looking to a new future for these areas. Who knows what they’ll look like? Maybe the changes won’t be readily perceived as positive as one way or another we’re going to be removing a lot of the trees that are here today. Should we take them all down in one go and let nature take over? Or should we do it slowly and gradually and try to control the process? There’s no doubt that this is a learning curve and public acceptance and participation will be key to its success” says Ciaran.

I share Ciaran’s enthusiasm for his sense of possibility. I’m especially keen as it’s near enough to where I live. The thought of setting off on a day’s hike from Ticknock, heading west to Tibradden and then the Featherbeds (recently incorporated with the Wicklow Mountains National Park) enveloped in the ethereal world of a shady woodland is heady.

But why stop there? Coillte Nature is just getting going. So far, it has a budget of €5 million and has identified nine of their properties in the Dublin Mountains for conversion. This is impressive but it is only a small part of the upland expanse which stretches all the way to Mount Leinster in the south. We should really be imagining a vast wild wood encompassing all of this land. In this context it’s just a first baby step. And what about facing the other direction? We know the forest can extend to the south, but can it also creep to the north, into the city itself?

Cities are frequently seen as the opposite of nature. Many people would take the view that nature’s place is in the countryside, where there’s space, while the city is for buildings and infrastructure. While we have lists of high value habitats which are not only located in, but are dependent upon, farming, there are no such views of urban areas as being worthy of such protections. Natural ecological processes are not seen to apply to towns and cities – it is simply the not the place for them.

But is this view correct? Can we imagine the metropolis providing essential ecological benefits, such as purifying water, storing carbon, producing food or recycling nutrients? We have become so used to the idea of cities as polluting and hostile to wildlife that we forget there is no particular reason as to why this should be.

Many of the Asian mega-cities are dangerously vulnerable to ecological breakdown; large parts of Indonesia’s capital Jakarta, for instance, is sinking by an astonishing 25cm per year (that adds up to a five metre slump in only 20 years at a time when sea levels are expected to rise by 16cm over the same period). Building on wetlands as well as excessive and unregulated extraction of ground water, itself a result of inadequate infrastructure to meet the needs of a burgeoning population, are combining with climate change to threaten this city of 10 million people.

Manila and Shanghai face similar issues. The response in Jakarta has been grandiose and expensive mega-projects based on heavy engineering. Following a devastating flood in 2013, the Indonesian government earmarked a whopping US$40 billion to build a 25km sea wall and a string of 17 artificial islands to seal off Jakarta Bay. But these hard solutions come at great ecological cost, frequently destroying coastal habitats or creating new problems elsewhere, e.g. where floodwaters are only diverted to other vulnerable locations.

Singapore, a wealthy city-state, has taken a different tack. Surrounded by the rising sea, it is also facing increasingly ferocious storms. In 2006 the city authorities, in contrast to their Indonesian neighbours, looked to nature for help.

Between 2010 and 2018 they completed 75 projects creating wetlands and opening up canals to provide natural storage areas for flood waters. They have been reforesting the city through their ‘Garden City’ initiative launched shortly after independence by their founding father, Lee Kwan Yew, who said “I have always believed that a blighted urban jungle of concrete destroys the human spirit. We need the greenery of nature to lift up our spirits.”

Singapore has a vision

Today nearly 10% of Singapore is protected for nature conservation, these reserves are linked up through a network of 180kms of ‘Nature Ways’ and 200 hectares of green space on the roofs of skyscrapers and other buildings. The city’s ecological approach to planning has saved it money, provides more reliable water for its citizens, has helped to attract jobs and investment, has created a pleasant place to live for families and is now a model for other cities across Asia which are facing similar issues.

Closer to home, London officially became the first National Park City in 2019 claiming to “want more bird song, ultimate frisbee, hill-rolling, tree climbing, cycling, hedgehogs, volunteering, sharing, outdoor play, kayaking, clean air, otters, greener streets, outdoor learning, ball games, outdoor art and hilltop dancing in the city”.

This was the brainchild of National Geographic Explorer Daniel Raven-Ellison, who told that magazine in August 2019 that “one in seven children has not visited a green space in the past year… I am talking about a cultural shift and challenging people’s notions of what their relationship with nature should be like.”

I found it hard to decipher what exactly is behind the designation, the website produced for the project does not cite a budget or whether the city authorities are to undertake any actual projects. There is advice for how local communities can get involved and there’s also a National Park City Foundation which will coordinate activities.

Too often (and we’ve seen it in Dublin) announcements which are high on branding but low on specific objectives amount to little more than greenwashing. It’s crucial to involve local communities but this must be met with top down support for initiatives including funding, expertise and – if required – enforcement of rules. There’s no doubt that it’s a bold vision, one which can transform how we see nature in urban spaces, but time will tell whether it produces measurable results.

I discuss this with Neasa Hourigan, then a Green Party councillor for the Cabra/Glasnevin Local Electoral Area in north Dublin (subsequently elected as a TD). At the time we spoke, she had been recently elected as part of the ‘green wave’ during local and European elections in 2019 which saw her party win two seats in the European Parliament (and nearly a third) as well as quadrupling their number of council seats.

The Phoenix Park: the city’s green lung, but it could be a lot better.

We meet in the Phoenix Park on a sunny August evening. Behind us, the ‘40 acres’, a vast open space usually inhabited by herds of fallow deer but occasionally taken up by papal audiences, such as the one that saw one million people throng to hear Pope John Paul II in 1979. In front of us lies a steep valley which descends into the Furry Glen, a quiet pond with water birds and fringed with mature trees. It’s a place I visited many times as a child when a small nature centre on the other side of the valley distributed maps for a wildlife ‘treasure hunt’ and which had a display of deer antlers and other artefacts from the woodland. It was a place for rubbing leaves with crayons and learning the tell-tale signs of squirrel gnawings on pine cones. The building is still there but hasn’t been used for this purpose for many years.

Shortly after Neasa’s election, the Office of Public Works (the authority responsible for managing the Park) issued a public consultation on what they referred to as a ‘Visitor Experience Strategic Review’ for Dublin’s biggest open amenity space. She was quick to notice that the plans for the Park amounted to little more than commercialisation of public space – with designs for expanded car parks and converting the charming gate lodges into accommodation for Airbnb.

Neasa galvanised public opinion in expressing their concerns for the plan, which can be seen as part of a wider trend which views parks and nature reserves as little more than assets for leveraging greater tourist numbers and economic growth.

In her submission to the consultation she called for more rewilding of the Park and I wanted to know more about what she had in mind. “There are too many wide open, manicured green spaces” she told me, “we could be looking at a lot more native woodland to bring a sense of wildness to these areas”.

Right enough, a lot of the trees are not native and while they might look great, they have fewer relationships with invertebrates, fungi or smaller plants than indigenous species. This all means that the biodiversity of the Park is a lot poorer that it might otherwise be.

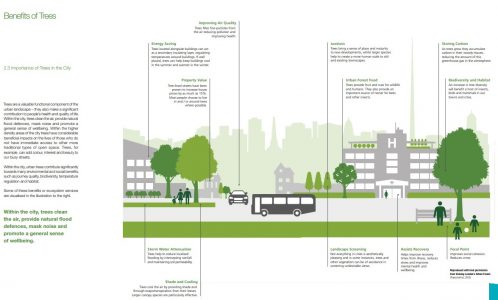

Neasa is adamant that we have to be looking everywhere for nature wins – “we need to be clawing back every green space,” she says emphatically. “Green space is mostly seen as recreational but it’s much more than that. Every single tree in the city is working flat out – we need to see them much more as essential infrastructure than we do right now”.

Indeed, the Dublin City Tree Strategy, published by the council, lists all the things that city trees do, including landscape screening to enhance aesthetics, storing carbon, saving energy by regulating temperatures around buildings, improving air quality, cleaning rainwater run-off and slowing its flow off hard surfaces, improving social cohesion, reducing recovery time from illness and injury and even bringing down crime rates.

The benefits of trees from the Dublin City Tree Strategy

The strategy acknowledges that, unlike most human-built infrastructure, the value of trees increases with time. It points out that there are an estimated 60,000 street trees and an additional 40,000 trees in parks across Dublin while overall it is estimated that tree canopy covers 10% of Dublin City.

This, says Neasa, is “average at best”. Right enough it is half as much as Cork, while in Stockholm it’s nearly 60%!

The other noticeable thing about trees in Dublin is what Neasa calls “a green apartheid”. This is the almost linear correlation between wealth and tree cover. Take a visit to Wellington Road in Ballsbridge, Dublin 4, one of Dublin’s wealthiest neighbourhoods and you’ll notice that it’s practically forested. The red-bricked mansions are barely visible in summer behind the leafy curtains of foliage.

This not only creates a pleasant vista but endows the street with a tranquility which muffles the traffic and calms the nerves.

Green apartheid?

Drive around less well-off districts and it’s a totally different story: bare concrete and wide, open plains of tightly mown grass that are instinctively repellent and alienating as well as providing nothing for wildlife. Unlike Dublin 4, these places subconsciously quicken the step, deter lingering and are boring just to look at.

Neasa contends that many of her constituents are more concerned about being evicted than about the quality or quantity of green space in their area. In this regard, meaningful green space can be seen as a luxury. But it isn’t. People in Cabra have an equal right to the benefits of a clean and vibrant environment to those on Wellington Road.

I bring up the issue of vandalism, particularly where new trees are broken or damaged quickly after being planted but Neasa wastes no time in dismissing this as an issue. “Place something new in an environment and it will become the target of vandalism – we won’t change that. We can break through that barrier so that trees are not seen as anything extraordinary, then vandalism won’t be an issue.”

She highlights how the City Council will provide trees to community groups but that those groups then need to maintain them. There’s also a need to train local people to become guardians of their green space, but the funding for this kind of outreach is not there. A new Tidy Towns group in her neighbourhood is bringing local volunteers together and there is hope that this will lead to greater pride of place as well as visible improvements. Neasa is adamant that the local authorities are not properly equipped to deal with the climate/biodiversity emergency and that reform will be needed.

She says there are too many councillors (63 on Dublin City Council alone while the actual urban area has four separate local authorities). Property taxes could be used for improving public spaces but councillors generally vote for keeping these low – and so money for enhancing the public realm isn’t there.

What could local authorities be doing? Maryann Harris is the Senior Executive Parks Superintendent and Manager of Biodiversity for Dublin City Council. Born and raised in the New York City area, she studied Landscape Architecture in Cornell University, New York before moving to Ireland.

When we met she was knee-deep in her PhD, which was looking at the management of UNESCO biosphere reserves in European cities. Dublin is lucky to have one of these extending across Dublin Bay. Much of the bay is also within the EU’s ‘Natura 2000’ network of protected biodiversity sites.

Bays and headlands at Baldoyle, Malahide, Howth and Bray enjoy similar protections. The city also has a small number of sites which were identified for protection in the 1970s – like the valleys of the Liffey and the Dodder Rivers – but the actual legal statutes were never forthcoming. The lines on the maps remain and if nothing else this highlights their presence to other would-be land users.

Unlike other countries, such as the UK, local authorities have no ability to create their own nature reserves or protected areas. So, the lack of even lines on maps can be disastrous.

In September 2019 a small wetland in Tallaght, within the South Dublin County Council area, was buried underneath nearly two metres of dumped spoil, something which was undertaken by the County Council itself.

Earlier in the year the wetland had been surveyed by the Herpetological Society of Ireland and its science officer, Collie Ennis, described the place as a ‘gem’ with abundant frogs, newts, invertebrates and bats. The council had been supportive of its protection but, it seems, nobody told the drainage department before they went out with their diggers. Lines on maps – so far the apex of conservation achievement in Ireland – do provide some protection. But we have to start realising the far greater value from these places through actual management and wardening.

Maryann goes further – she thinks these places also need buffer zones, as exist for the Dublin Bay Biosphere Reserve, and we need to be measuring the effectiveness of protected areas. “Are they doing what they are supposed to be doing? We don’t know! The protected areas are isolated and they should be joined up to local areas if we want to get the most from them”.

She’s excoriating of past failures, including how the city lost its red squirrel population “by choices which disregard urban biodiversity in national policy” but ultimately protecting nature will require land acquisitions – something that is expensive and contentious. “We can’t buy new green space,” she says, but she points to a trend in the United States that is seeing what she refers to as ‘unbuilding’, chiefly the demolition and return to green space of retail centres which have closed due to online competition.

Red squirrels were common in Dublin up to the 1980s. Image source: Mike Brown

The idea of tearing up concrete to create more green space is not as crazy as it might sound. In fact, it’s already being done in cities like Paris where three new parks were created in 2019 in some of the most densely populated parts of the city and with a collective area the size of the Parc de Princes sport stadium.

These are integrating play spaces for children along with native trees and even wetlands. Parisian city authorities are also investing €5 million in a new linear forest which is envisaged will hug the busy Périphérique motorway.

These initiatives are multifunctional, reducing noise pollution, adapting to climate change and expanding opportunities for contact with nature in disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

Anne Hidalgo is major of Paris and chair of the ‘C40’ coalition of cities – an organisation dedicated to leading the fight for climate action in the face of state recalcitrance. She told TIME magazine in September 2019 that “wherever possible, we are removing asphalt to give space back to nature. Soon, the Eiffel Tower will sit in the middle of a large park. With tree planting programmes, real urban forests will act as lungs for neighbourhoods across the city.”[iii]

The New York Times declared that “she has positioned herself prominently among the mayors of the world’s premier capitals as an advocate for what she bills as a new, and necessary, kind of urban landscape”.

Measures have included closing off the right bank of the River Seine to traffic, transforming a highway in the heart of the city into a pedestrian and cyclist thoroughfare with cafés and greenery, as well as 8,000 other projects which will see nearly 1,000km of dedicated cycle lanes in a city notorious for its traffic jams and poor air quality.

Her approach has not been universally popular, provoking the ire of motorists in particular. There has been disruption and the opposition has been fierce at times, something Mme Hidalgo attributes in part to sexism. “Part of it has to do with being a woman. And being a woman that wants to reduce the number of cars meant that I was going to upset lots of men. Two-thirds of public transport users are women,” she told The New York Times.

But the results have been impressive: car ownership has nearly halved since 2001 while its ranking as a bike-friendly city has risen to eighth place in 2019 from 17th in only 2015. In June 2020 Hidaldo was re-elected mayor while TIME magazine declared her among the 100 most influential people of that year.

Trees and other natural vegetation just need some soil to flourish.

Demand for space in cities is intense. But only our perspective needs to change to see where the opportunities lie. Seen from above, cities like Dublin can seem like expanses of grey, empty space. Roofs have been viewed as of little value except for air conditioning vents and plant rooms. But this is changing as people see the opportunities of converting acres of impermeable roofs to green spaces and even farms.

A ‘green roof’ can serve many purposes – from replicating the amenity value of a park or garden in the sky, to cleaning and slowing the flow of rainwater run-off. The plants chosen can be pollinator-friendly and can even attract ground-nesting birds (threatened species of seagull such as the herring gull and black-backed gull are already nesting in numbers on Dublin roof tops).

‘Blue roofs’ can be designed with constructed wetlands to store rainwater which can then be used for flushing toilets – cutting down on water demand and reducing pressure on municipal drainage pipes (overflows during storms are a frequent cause of pollution in Dublin Bay).

The world’s largest roof-top farm opened in Paris in 2020 with 14,000m2 of fruit and vegetable plots which are expected to produce 900kg of produce every day during high season.

When we think about how car-sharing and self-driving cars are expected to drastically reduce the numbers of private vehicles on our roads in the coming decades, we can quickly see how the space for safe walking, cycling and greenery becomes available in abundance.

Between road space and surface car parking it is estimated that some cities in the United States devote 50–60% of their downtown areas to cars. Even if this figure is likely to be much smaller for a city like Dublin it clearly demonstrates the phenomenal cost to communities from private car usage. Deaths from traffic accidents and air pollution, noise, congestion and chronic respiratory conditions would be eliminated. The opportunity cost from not having safe, clean, shared spaces for lingering and moving around is staggering. So staggering, that in the future we will surely look back in horror and wonder how we tolerated such unhealthy urban environments.

Maryann also highlights the need for cities to look beyond their boundaries. “In terms of flooding and water quality government bodies should be trying to control land use at the headwaters of rivers flowing into the city so they can be best managed for water quality and flood prevention. We are spending enormous money at the bottom of the catchment building walls that are detrimental to biodiversity but very little in comparison to softer measures upstream. It should be done on a regional basis but our government structures are very weak at that level, due to the political constructs we reinforce through local parish pump politics. It’s all very small, parochial and short-term when what we want are sustainable, communal and long-term decisions for biodiversity and climate change.”

This point was brought into sharp relief in early November 2019 when 600,000 Dubliners were placed on a boil water notice. Water from the treatment plant at Leixlip, to the west of the city, was contaminated with the harmful microbes cryptosporidium and giardia and according to the media reports at the time, the water was undrinkable due to the lack of certain filters and disinfecting UV lights at the plant.

Dubliners get their water from the Wicklow Mountains but the landscape is badly degraded.

There was no commentary that I was aware of which asked why water in the River Liffey, upstream of the city, was contaminated with organisms which are products of human and animal waste. Anyone following the course of the Liffey into its headwaters would trace it through a landscape of farms and one-off houses associated with animal run-off and malfunctioning septic tanks, before reaching the Wicklow Mountains, themselves dreadfully degraded from peatland erosion, plantation forestry, sheep grazing and fires. Restoring these landscapes would serve to protect the drinking water supply for the city if only we could see the connections.

Maryann’s office, and others like it in the greater Dublin area are doing what they can on the meagre resources they’re given. She tells me how they are mapping and restoring urban wetlands, surveying remnant populations of frogs, working with local schools to foster connections with nature and creating urban woodlands. But getting decision-makers to see nature as anything more than a second or third tier issue is a struggle.

The Climate Change Action Plan for Dublin which was published in 2019 recognises that nature-based solutions are “critical in climate change adaptation”. The city faces some significant climate challenges, including predicted sea level rise of at least a metre by the end of the century, increased storm surges, greater wave height, flooding and other weather-related pressures.

Sea level rise is set to transform Dublin. c. Dublin City Council Climate Change Action Plan.

Indeed, some of the maps in the plan are frightening – showing much of the central and eastern portions of the city at risk of inundation. Flood alleviation schemes are likely to swallow much the budget for climate adaptation programmes. Actions under the plan which fall under nature-based solutions, and which are budgeted, are entirely based on holding workshops and developing strategies. Actual work on the ground, including pilot projects to install green roofs on civic buildings and demonstration sites to showcase nature-based solutions in action are highlighted as ‘awaiting budget’.

One positive project that is under way and which is proving the value of nature is along the River Tolka, a shortish river which runs for most of its course through urban parts of north Dublin. It has long been among the most polluted rivers in Ireland, chiefly through a combination of road run-off and what are known as ‘misconnections’. Misconnections are where drainage sewers from industrial and housing developments were plugged into the pipe leading to the local river rather than the one going to the treatment plant at Ringsend.

It has meant that industrial discharges, raw sewage, waste from washing machines, dishwashers and showers flows unimpeded into the River Tolka. Near where I live, the river flows through a densely wooded valley before opening onto a floodplain that is a haven for wildlife. I have seen kingfishers and otters while the lack of general access or management lends the area a wild lushness that belies its proximity to the M50 motorway and sprawling Blanchardstown Shopping Centre.

But the water is foul. It tends to stink like the basin of dirty dishes you didn’t get around to before going on two weeks’ holiday. It is grey and murky. When it washes over the floodplain it deposits a wave of fertiliser loved by nettles, some of which are nearly two metres tall in late summer.

Urban rewilding: full of wildlife and protecting downstream areas from flooding.

In 1999, in response to a particularly foul misconnection near Glasnevin, the city council installed a specially designed wetland. The idea was to harness the natural ability of microbes to break down the pollutants found in domestic wastewater. Using a variety of native plants including yellow flag iris, willows and bulrushes, the wetland serves to slow the flow of run-off for long enough to allow the bugs to do their work – turning nitrogen and phosphorous into nutrients which can be taken up by the plants and neutralising harmful bacteria. With no working parts, the wetland requires virtually no maintenance. Instead of roaring pumps and belching emissions, the wetland rings with birdsong and the hum of dragonflies.

Work is now under way to address misconnections further upstream and the Tolka is among 190 ‘priority’ water bodies across Ireland. This aims to achieve ‘good status’ by 2021, something which was supposed to have happened by 2015.

The Dublin Climate Action Plan identifies how repeated flooding events along the Tolka have swamped homes and business in recent years, including November 2000 when nearly a metre of rain fell on the city in one downpour, affecting 250 properties. The Tolka River Valley Greenway is in part a response to this – demonstrating the multi-functionality of green spaces for people and wildlife. Although the river is still terribly polluted, in 2011 Atlantic salmon were spotted in its lower reaches for the first time in over 100 years. Nature, it seems, is ready to forgive our worst transgressions.

Reimagining the city should not stop with our rivers, parks and mountains. Dublin has always been a coastal and maritime city and until relatively recently fishing boats plied the bay, selling the fruits of the sea at Irishtown and Dun Laoghaire. Oyster reefs spread out from Ringsend and Clontarf but have been totally extirpated. Could they come back? Oyster restoration projects are under way in the UK and USA and, tentatively, even in Ireland. Nearly everywhere it is tried it has been successful. In protecting the seas – with its beds of sea grass, forests of kelp and natural reefs – we are also taking climate action as these habitats are proven to store carbon and reduce the intensity of storm surges. Marine Protected Areas work – in fact conservation, in general, works.

This holds just as true in the city as it does in the countryside.

Dublin could be heaven. c. Jacek Matsiak.

[i] Cooney T. 2018. North Bull Island Bird Report 2017 (www.bullislandbirds.com).

[ii] Braczkowski et al. 2018. Leopards provide public health benefits in Mumbai, India. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. Vol16 Issue3 pg176-182

[iii] ‘Our cities cannot become climate sanctuaries for the rich’ by Anne Hidalgo. TIME. September 23rd 2019.