And precious their tears as that rain from the sky

Which turns into pearls as it falls in the sea

by Naomi McBride

The water was slightly murky but as the swirling vortex slowed I could see the outlines emerge from the bottom of the tank. Even then it took a few moments for my eyes to adjust; the colour and shape of the creatures perfectly blending with the dark rocks which had been placed around them for support.

I had been expecting more for some reason, but there were only a handful, ten maybe, in the tank. A far cry from the thousands, perhaps even millions, which once formed their company. They seemed lonely to me and their fate desperately precarious as I stared at them, leaning over the side of the plastic tank that was their temporary home.

“You should have been here yesterday,” Paul says. “The water was crystal clear. But it rained a lot overnight and that washes sediment into the water so unfortunately the view is not so good today”.

I stare at them a bit longer and Paul points out the small trout. I would have missed them as they too are perfectly camouflaged – dark backs against the black stones. I was expecting the fish to be bigger but Paul explains that they have to be young fish if the project stands any chance of success. Then he turns the pump back on and the water starts to swirl again. It’s important that the water keeps moving to provide oxygen and a constant supply of tiny food particles. “It’s terribly sad to see them going extinct, but we’re going to do what we can,” he says.

Freshwater pearl mussels. Image source: Eugene Ross

The freshwater pearl mussel is a bivalve, belonging to the family of invertebrates which have two shells joined by a hinge, like the common blue mussels which are enjoyed with chips or the cockles and clams which are similarly prized by gourmands.

As an icon of conservation, alas, it fails on many fronts. It is fairly plain to look at, practically no one has heard of it or could identify it among a bivalve line-up, and it’s the opposite of ‘charismatic megafauna’ – with no eyes or fur and no behaviour to endear it to an internet audience.

Yet there is much more to this mollusc than meets the eye. Beneath its bland and sedentary exterior there sometimes dwells within a pearl as alluring and lustrous as any from its marine bivalve cousins and for over a thousand years these have been greatly sought after in Ireland.

The Tuatha Dé Danann, a mythical race of deities, knew that swallowing a pearl would endow them with the gift of eternal youth. There are suggestions that the Phoenicians traded with Irish pearl collectors in ancient times while their association with high status and royalty can be seen on the façade of Dublin’s Custom House, where Edward Smyth’s representation of the River Bann is crowned with strings of pearls[i].

But the folklore pales in significance when compared to the story of freshwater pearl mussels themselves. In Irish waters they are known to live to well over 100 years old, while in more northerly regions they may reach twice that and so are among the longest-lived animals in the world.

Adult mussels spend most of their lives rooted in one spot, usually in rivers though they are historically also known from a number of lakes. Males release their sperm into the water which the nearby females then inhale.

The fertilised eggs are nursed within the mother’s bosom until conditions are right, when, following cues which may be linked to temperature or movements of the moon and stars (no one knows!), they spawn in unison, sending billions of fertilised eggs in a cloud of pearl mussel plankton to be carried by currents downstream.

The tiny larvae are on a mission. To survive, they need to be inhaled by a salmon or trout and as they pass through the fish they will clasp themselves to the gills where they can develop in safety for about a year.

When they are ready, the young freshwater pearl mussels – known as glochidia – will release their grip on the gills and sink to the bottom of the river. A tiny foot then gropes in the gravel for just the right spot and then, when satisfied, it will orient itself, supported by the surrounding stones, for its filter-feeding future of a century or more.

At somewhere between seven and 15 years of age it will be sexually mature and will remain fertile, producing billions of young, right until its death.

Commercial exploitation of mussels typically involved extracting the animals from their riverbed home and opening the shells to see if there was a pearl inside. This invariably resulted in the death of the mussel and since only about 1 in 1,000 actually had a pearl the process was massively destructive and wasteful.

Overfishing of whole catchments is known to have occurred so that by the early 1900s the commercial exploitation of pearls had more or less ‘died out’[ii].

Nevertheless, the mussels’ prodigious ability to reproduce along with intact river systems and the great numbers of salmon and trout surging through them, meant that populations remained widespread, if much reduced in absolute numbers.

But in recent decades the mussels have stopped reproducing. Land use change not seen since the felling of the ancient forests has transformed the landscape. A combination of malfunctioning private septic tanks, crumbling urban wastewater treatment systems, industrial forestry and farming activities, obstructions along rivers such as hydroelectric dams as well as landscape-scale drainage of land has led to a collapse of our natural river systems.

The mussels, adapted to clean water, have not coped with this transition and are disappearing. Since the introduction of the European Union’s Habitats Directive in the early 1990s the freshwater pearl mussel has been a protected species and back then we committed to restoring populations.

But this has not been effective. According to the latest assessment (2019) from the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) many populations have decl ined within the last decade to the point of near extinction stating that:

“the observed acceleration of population decline and further decreases in recruitment rates are alarming and raise questions as to the restorability not only of the small populations on the verge of extinction, but also of some priority populations with hundreds of thousands or millions of mussels. […] Riverbeds have become so clogged with silt, algae and rooted plants that young mussels can no longer survive. In many rivers, adult mussels have become stressed and are prematurely dying owing to habitat deterioration”[iii].

Paul Carroll works for Waterford County Council at the water treatment plant in Kilmeadan, just west of Waterford Town. Here, water extracted from points within the catchment of the River Suir is treated to a drinkable standard in a series of tanks before making its way to homes and businesses in the Waterford area.

Two years previously Paul joined with local groups to improve the lot of the freshwater pearl mussels which live along the Clodiagh River, a tributary of the Suir.

With assistance from Irish Water, the body that runs the treatment plant, Inland Fisheries Ireland, the NPWS and Dr Evelyn Moorkens, the foremost authority in Ireland on freshwater pearl mussels, he has set up two tanks where he hopes the mussels can be captive bred.

“We originally thought there were over a thousand mussels left in the Clodiagh River” he tells me, “but our most recent surveys tell us there’s now maybe less than 100. We’re failing to protect them… you’d need to be super optimistic to think we’re going to meet the targets”.

The targets he refers to is the Special Area of Conservation along the Clodiagh River which was designated specifically to restore ‘favourable status’ to the mussel population. In particular a target of restoring the population to 10,000 mussels was identified in a 2017 NPWS report.

Paul winces when I ask him how he thinks this population is going to be restored. “The youngest mussel we have is 40 years old. There are no young mussels surviving to adulthood, with the very low numbers now in the river they may be gone completely in 10 years or so. The clock is ticking.”

Paul brings me round the back of the main building to show me the captive breeding tanks which he has set up. He explains how the glochidia need to attach themselves to the gills of a salmon or trout but as the fish grow they develop an immunity which prevents the glochidia from attaching. Hence the need to use young fish in the tank.

He tells me that while the adult mussels are surviving and spawning and the glochidia are finding their host fish, when it comes time for the larvae to drop off the fish the river bed is too clogged with silt and sediment, and the water quality too poor, for them to develop into adults. An ancient cycle that has been turning since the end of the Ice Age has creaked to a halt.

“We’re taking a twin-track approach,” Paul explains. “We are trying to artificially create conditions to rear the mussels up to about five years of age, then we can put them back in the river when they can survive on the own. But we also need to work at the catchment level to stop the pollution entering the river in the first place. And that’s a massive challenge”.

Paul is working as part of the Local Authorities Water Programme, something which is bringing together communities to highlight the value of clean water as well as to promote solutions to issues faced by the river.

This was established as part of Ireland’s implementation of the EU’s Water Framework Directive, something which stipulated that all our waters were to have achieved ‘good status’ by 2015 except where there were exceptional circumstances. As well as greater cooperation and communication, a team of ‘community water officers’ has been hired.

They are surveying entire river catchments to identify pollution sources and putting a human face on government initiatives. When it comes to conversations with farmers and landowners Paul concedes “it’s a delicate discussion”.

They have no extra money to offer farmers for changing practices. The solutions which are commonly promoted such as leaving buffers along streams and ditches, digging sediment traps and fencing rivers to keep out livestock are important but small steps (as I write some funding is being sought to implement some of these solutions).

What’s really needed is a transformation of agricultural policy, that’s the Common Agricultural Policy which is decided among the 27 nations of the EU and, with the departure of the UK, is likely to see a cut in its budget.

But Paul and the Local Authorities Water Programme (LawPro for short) have allies.

The Portlaw Heritage Group, based at the bottom of the River Clodiagh catchment, have understood the importance of the freshwater pearl mussels in their local river and have taken the conservation project under their wing.

With their help, LawPro are setting up a “Friends of the River Clodiagh” group to include the villages of Rathgormack and Clonea along the entire river catchment.

Paul drives me about 20 minutes outside of Kilmeadan to the magnificent Curramore House estate, home to the ninth Marquis of Waterford and a Victorian mansion which surrounds a castle dating to the 12th century.

It was built by the de la Poer family which came to Ireland from Normandy at the time and sits within 2,500 acres of land including woodland and grazing pastures along the banks of the Clodiagh River.

The current manager of the estate, Alan Walsh, is a keen supporter of the freshwater pearl mussel project and is not only helping to improve the water quality running off his land, but has offered the use of the Curramore Stream, a rivulet that flows into the Clodiagh, as a donor site for Paul’s captive-reared mussels. The surrounds are idyllic, with dense woodland and formal gardens which draw the eye to the impressive old house.

Paul and I stand on a bridge looking down on the clear waters below. The early winter air is cold but fresh and the colours of the fading leaves are exquisite.

“It’ll be an ideal site” he says, “not only as a refuge for the mussels but as a place where walkers can see these most threatened species in their native habitat. We hope we can install an information panel that will help to tell the mussels’ story to the passers-by.”

Because the Curramore Stream is small, and originates on the land within the estate, the water quality can effectively be controlled. But once the mussels enter the main channel of the Clodiagh River they’re subject to all the pressures from throughout the catchment – from the degraded uplands to the intensively farmed fields in the lowlands.

When I visit Paul in November 2019 he tells me that he is awaiting a visit from Dr Moorkens who will examine the small trout for signs that the tiny glochidia have attached themselves to the gills. Then it will be a question of waiting for the glochidia to fall off and nursing them to the point where they can survive by themselves.

When I look at the fairly low-tech plastic tanks and pumps used to keep this project going, and when I see Paul prepared to devote years of his own time in providing the slimmest lifeline to a vanishing species I can’t help but feel conflicted. Full of admiration for what he is doing and a surge of hope in the face of our extinction crisis yes – but also a feeling of despair that the response is not greater.

If the freshwater pearl mussel is to survive, we’re going to need a lot more tanks and a lot more people like Paul.

Three weeks later he sends me an email: “Just to let you know that Evelyn [Moorkens] was down today to check the gills and there was good glochidial encystment! [the larvae attached to the fish] Plenty more work to do but it’s great to get a positive result for now.”

For the moment, hope has the edge in the fight to save the mussels.

—

Over-grazing, burning and erosion of peat in the uplands along with clear-felling of conifer plantations leaving swathes of bare soil are all sources of sediment washing down from the hills.

But when rivers reach the lowlands they enter the large agricultural areas. Here, modern farming promotes land drainage which changes the pattern of water flow – faster in flood and drying out quickly in drought – and which can carry large quantities of sediment off the land.

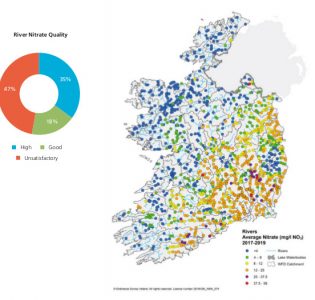

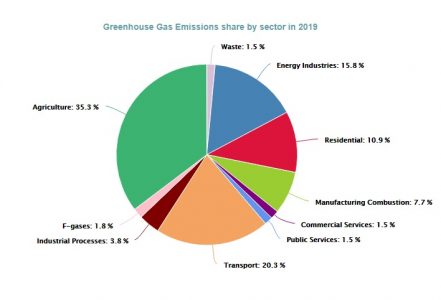

Pollution of rivers from nitrates is concentrated in the south-east of Ireland (Image source: EPA).

Ploughing fields exposes soil to the elements while leaving fields bare after harvesting crops (typically during the wet winter season) is another source. But even so-called ‘permanent pasture’ where cows are grazed outdoors for most of the year is now a problem. Pollution comes from nutrients in manure and artificial fertilisers, land drainage and disturbance of soil from the trampling of hooves.

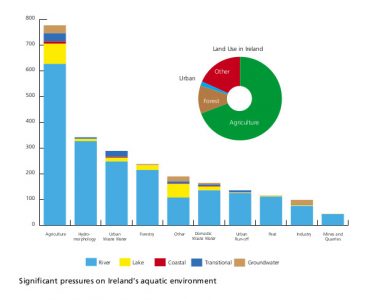

According to the Environmental Protection Agency farming in Ireland is the greatest source of water pollution, not only sediment but run-off from manure and chemical additives such as artificial fertilisers and chemical sprays. In 2019 their report on the status of our waters shows a near disappearance of ‘high status’ water bodies and a reversal of previous trends which had begun to show an overall improvement. It is not a coincidence that the decline of the pearl mussel has matched that of our water quality.

Agriculture is the dominant pressure on water quality in Ireland (Image source: EPA).

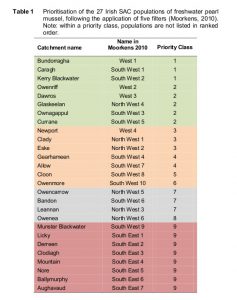

In 2011 the government prepared a strategy for the conservation of the freshwater pearl mussel in Ireland. It highlighted how we have 46% of the entire EU population, emphasising not only how the mussels have declined throughout their range but also the vital role we must play if they are not to go extinct entirely.

Under the Habitats Directive Ireland designated 19 Special Areas of Conservation holding 27 populations of mussels. The plan stated at the time that out of 96 populations only one was assessed as ‘favourable’.

In assessing mussels’ prospects it differentiated between those areas where there are still relatively high numbers in a small river catchment and where conservation measures were likely to produce results, and those where mussel numbers were low, in very large river catchments and where it was felt that the measures required would not be successful – at least in the short-term.

It concluded that eight populations, all of which are in the north and west of the country, should be given top priority and since the plan’s publication we have seen the roll out of special programmes to address pollution in these areas.

However, as we move down the list it becomes clear that the scale of the task to save the mussels becomes overwhelming. Eight of the catchments, all of which are in the highly productive farming areas of the south-east and south-west, have a mere 0.35% of the national population with what the plan describes as “a large number of significant point sources and highly intensive agricultural land use over large areas of the catchment.”

It went on say that “it is unlikely that any of the six south-east populations… can be restored” and recommend that the efforts to protect these mussels should be wound down, even going so far as to suggest that the protections be removed from some areas altogether, such as the Rivers Suir, Slaney, Nore and Barrow. Such a strategy would mean the swift extinction of freshwater pearl mussels from the entire south-east. It’s also a strategy which appears to be working.

As part of the research for this project I tried to get to the bottom of why it has been decided that freshwater pearl mussels are to go extinct from rivers where it has thrived for thousands of years.

Is it because it is too expensive? The NPWS report states that “it is very unlikely that [conservation] measures, if applied and irrespective of cost, would be effective”.

Or is it just that it’s too difficult? We have laws in place, many of which were passed years ago, to clean up our waterways and ensure that endangered species like the pearl mussel are restored to health. Yet these have not been effective because they have not been implemented with any degree of enthusiasm.

It’s all about priorities (source: NPWS)

Apart from the moral conundrum, is it even legal to decide that the freshwater pearl mussel can be jettisoned because the challenge of saving it is too great? The answer, thankfully, is no.

While in 2018 then-Minister for Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Josepha Madigan, removed the freshwater pearl mussel from a list of conservation objectives for the River Blackwater in County Cork, the High Court found in favour of a legal challenge to this decision – so the protection remains.

When you appreciate just how clean the water needs to be to allow the juvenile mussels to proliferate, they can seem unreasonably exacting in their demands. Certainly, they seem far fussier than any other animal that we know of – more so even than fish like the Atlantic salmon which is also suffering from the effects of water pollution.

But then this shows just how much we have affected our river systems – the mussels, after all, were prolific in their reproduction for thousands of years.

It’s only since the 1950s that things started going seriously downhill for them. So what would it take to restore our rivers in the south-east? Investing in wastewater treatment plants for towns and cities is a financial decision and so should be straight forward.

Giving local authorities and the Environmental Protection Agency the resources to enforce provisions for private septic tanks, quarries and sand pits is similarly a financial decision. Which leaves us with the elephant in the room – farming.

Changing how we farm is not merely a decision on how we spend public money, though it is that. It is also a cultural and social domain. The food industry is deeply embedded within the export-driven, growth-fixated psyche which lives like a parasite in the brains of economists, politicians and civil servants. Fixing the issues in agriculture means evicting the invader. And if we’re to measure success in this endeavour we need look no further than an inconspicuous, dark-shelled mollusc which, very occasionally holds within it a pearl of the most exquisite beauty.

—

The valley of the River Suir, along with its sister rivers throughout the south-east of Ireland – the Blackwater, the Nore, the Barrow and the Slaney are the main (read profitable) agricultural-producing areas in Ireland. These are the areas renowned for centuries for their fertility and are the centres of Ireland’s more recent boom in dairy farming.

The removal of dairy quotas in 2015 has seen a rise in income for farmers in this sector, the only sector of food production in Ireland which is profitable (although still heavily dependent upon subsidies).

As well as the issue of water pollution, agriculture in Ireland is the largest contributor to Ireland’s greenhouse gas emissions and the greatest driver of species extinction and so is operating way beyond the limits of nature.

While exports of food and dairy products like powdered milk are booming, prices for farmers’ produce, particularly beef but also sheep, vegetables and grains, is static or falling.

In 2019, the head of the farm advisory body Teagasc, revealed that farm incomes had dropped by 20% on the previous year to €23,482 and warned that 30,000 farmers face poverty. That year saw a splintering of farm representative bodies and blockades of meat plants by angry beef farmers because of low prices.

The popular RTÉ programme Ear To the Ground claimed in December 2019 that the number of vegetable growers in Ireland had halved in the last 20 years with a mere 160 growers left in the country. Even in the much touted dairy sector, the number of dairy farmers has fallen from 80,000 in the 1980s to only 18,000 today. In what has been referred to as the ‘dairy paradox’, industry expansion actually means fewer people working the land.

Farmers blame supermarkets for the squeeze but they are also feeling the pressure to improve their environmental performance alongside a growing cultural shift towards veganism and vegetarianism. There are some who suggest that farming itself is coming to an end as food technology will advance to the point that all essential nutrients can be artificially manufactured from widely available resources – effectively creating food out of thin air.

Farming as it was known for thousands of years went through a transformation in the post-war years. Whatever happens now, it’s about to go through another one. Can this be done in a way the saves farmers and beleaguered species like the freshwater pearl mussel?

—

There are farmers who are finding a way.

It’s Halloween when I roll up the driveway to the home of James Foley. James is a dairy farmer in the townland of Cooleydoody in County Waterford. He comes from a farming family and his father is still farming in Dungarvan, not too far to the south-east of here.

His wife, Clodagh, also has farming in her blood and together they are raising their young twins in this bucolic corner of Ireland. James and Clodagh’s farm lies on the brow of a hill overlooking the surrounding green fields and hedgerows.

Not far to the north flows the River Blackwater, a renowned salmon river and one which was once home to healthy populations of freshwater pearl mussel. Today, the water quality is decent enough and the salmon fishery is among the few in Ireland which is open to catch and release angling, but the pearl mussels are not doing so well.

One of the tributaries, the Lickey, saw its population plummet by over half between 2005 and 2009. But despite government efforts to remove protection for the species in the river, there are still many thousands of mussels and it is one of the few rivers where juveniles have been recorded. There must surely be hope yet for recovery.

James has been trying something new on his farm and soon after a dinner of homecooked ham and cabbage he enthusiastically grabs his shovel, beckoning me to follow him through the yard and onto his experimental field. His field looks different for a start – although it’s nearly November the plants are still waist-height.

“I get farmers looking over the hedge at it, they think the field is rough looking, they think it’s full of thistles” James says.

It is rough looking, not like the carpets of shiny green fields that we’re used to looking at. For many decades, farmers have been encouraged to seed their fields with a single species of grass – perennial rye mostly – a grass that has been referred to as the ‘Ferrari’ of Irish dairying.

This monoculture has been largely responsible for the loss of wildlife from the centre of fields but it also means a monoculture in the bits we can’t see: the soil.

Replacing natural diversity with homogeneity affects the structure of the soil, reducing the level of biological activity and leading to poor health of the soil overall.

“Most soil in Ireland is practically inert” James asserts. “We’re told to reseed with just one grass species and then douse it with artificial fertiliser to grow as much grass as possible. But this is terrible for the soil – most of the nitrogen ends up going into the air or washing off the land”.

James is right; although soil is an enormous store of locked-up carbon, in Ireland monoculture fields are greenhouse gas emitters, due to the methane from the animals themselves but also due to the nitrous oxide which comes off the fertiliser.

Artificial nitrogen has also been referred to as the ‘crack cocaine’ for perennial rye, a dependence that costs farmers thousands of euro every year to maintain the high. In 2018, at the height of a drought which stretched through the Irish summer, James reseeded one of his fields. But this time, instead of just one species, he sowed a mixture.

Among the plants were chicory, which has pale blue flowers that are popular with bees, ribwort plantain, an inconspicuous plant with roots up to a metre in depth, and bird’s-foot trefoil, a native species also popular with bees and which, being a legume, can fix its own nitrogen from the atmosphere.

Bird’s-foot trefoil is also a food plant for at least five of our butterfly species. James hopes that other native plants will colonise the field over time. “The hedgerows about the farm are full of native wildflowers and are a bank of biodiversity” he says, “hopefully some of them will make their way into the pasture. We’ve known for a long time that hedgerows are great for wildlife, but we want to get nature back into the centre of the field – that’s where most of the land is!”

Bird’s-foot trefoil: good for butterflies, good for soil fertility

Despite the drought, the plants flourished. “You should have seen the amount of butterflies in this field over the summer, and there were none in the one beside us. You could even see there were more swallows over this field because there were more insects generally.”

James clearly gets great pleasure from seeing wildlife return to his farm, but this is not the main reason why he wants a diversity of plants growing in his field. “I have a family, I have to make my farm profitable. I think that learning from nature can improve the health of my animals and reduce my costs – I’m not putting any artificial fertiliser or pesticide sprays on this field” he says.

James is part of a group of farmers in this part of Ireland who are promoting ‘regenerative farming’. It has been described by the scientists behind the Drawdown Project as farming which includes “no tillage, diverse cover crops, on-farm fertility (no external nutrient sources required), no or minimal pesticides or synthetic fertilisers, and multiple crop rotations, all of which can be augmented by managed grazing”.

The Project ranked regenerative agriculture at 11th in terms of its potential climate benefit, calculating that it has the potential to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 23.15 gigatonnes and savings of US$1.93 trillion by 2050[iv] (former US vice-president Al Gore is a fan). It has elements of the more familiar organic farming but chiefly the difference is the focus on the soil. The report produced by the Regenerative Farming Ireland group states: “Regenerative agriculture is about working with nature’s many natural cycles to provide nutritious food with a minimum environmental footprint. It is also about the regeneration of the families that are at the heart of so many food systems. It is about their economic viability and their rewards being derived from the consumer, not the taxpayer.”

James and his colleagues are joining the dots between the multiple pressures facing farmers and have found that the answer to many of their problems has been largely under their feet all along. To demonstrate what we’re talking about, James seizes his shovel and drives it into the ground. He does this repeatedly, at right angles, lifting a cube of earth and laying it to one side.

There are farmers who are joining the dots

We crouch down and peer into this small pit. “The chicory has a deep tap root,” he explains, “and this breaks up and aerates the soil much deeper than the perennial rye grass. This means rainwater can percolate deep into the soil, something that can’t happen where the soil has been compacted”.

The earth in his hands is quite dry and crumbly and it’s full of worms – this is a good sign. Earthworms are vital for soil health but a study from England showed that worms were rare or absent from 40% of fields[v] (we have no information from Ireland about the worms or the biological health of the soil more generally).

Deep roots and earthworms greatly improve drainage and this works to the farmers’ favour during times of drought (as the plants can avail of water stored deeper in the soil) and at times of flood (absorbing water that would otherwise sit on top of the field). James repeats the test in his neighbouring field, where there is only one type of grass plus some clover. Here the soil is noticeably different, much more gluey and dense, and not so many worms. His cattle enjoy grazing the variety in their new field and, so far, he has noticed no difference in his productivity.

But the advantages of this approach don’t stop there. Green plants actively photosynthesise light and transfer liquid carbon through their roots into the soil. Taller plants, with more leaves and more varieties of them, do this with much greater efficiency than a thin layer of one type of grass. James is availing of an abundant and free source of carbon and nitrogen which are contained in the air at all times and using them to build resilience and fertility in his land.

Grazing cattle leave their dung on the ground to be colonised by dung beetles. The beetles, of which a number of species have been identified in Irish fields, actively carry the dung back into the soil where the nutrients are recycled. There is even evidence that dung beetle activity can reduce the amount of methane from the cowpat by burrowing into and aerating it, thereby reducing overall greenhouse gas emissions[vi].

The widespread use of ivermectin to combat parasites in cattle, and which is toxic to dung beetles, has led to the decline of these important insects on Irish farms.

Dung beetle

Meanwhile, the structure of the vegetation, both above and below ground, holds the soil together, meaning erosion is virtually nil and, because fertility comes from nature and not a bag, the pollution from artificial nitrogen use is avoided.

Regenerative techniques, if used alongside much greater tree planting on farms, active hedgerow management and the protection of river corridors through the creation of broad buffer zones where farm animals are excluded, hold the key to eliminating water pollution from agriculture and reducing the greenhouse gas emissions from Irish farms.

James’ field is small but he hopes to expand his multi-species meadows to the rest of his land in the coming years. He’s one of thousands of farmers in the Blackwater valley where, if regenerative farming became the norm, the effects would literally trickle down to the river where we could see the freshwater pearl mussels rebound.

—

Environmentalists are frequently heard calling for Irish farmers to diversify away from a reliance on beef and dairy. It’s one of the central themes of the Regenerative Farming Ireland manifesto.

Beef and dairy in particular are under fire for the large environmental impacts associated with the way they are produced in Ireland. Many consumers have responded by turning to vegetarian or vegan diets while farming groups have reacted angrily, pointing to the large environmental impacts of some plant foodstuffs such as imported avocados or almonds. Yet the science is clear.

In 2019 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published their special report on land, stating that:

“balanced diets, featuring plant-based foods, such as those based on coarse grains, legumes, fruits and vegetables, nuts and seeds, and animal-sourced food produced in resilient, sustainable and low-GHG [greenhouse gas] emission systems, present major opportunities for adaptation and mitigation while generating significant co-benefits in terms of human health”.

So major dietary shifts are needed. But it’s not as simple as reducing the argument to meat/dairy versus vegan. As farmers like James are fond of saying: ‘it’s not the cow, it’s the how’.

But in Ireland, only a tiny fraction of the meat and dairy products we produce, not only from cattle but also sheep, pigs and poultry, can be considered to be from ‘low-emission systems’. The IPCC also highlighted the need to reduce food waste, currently between 25 and 30% of all food produced is thrown out, something which is responsible for up to 10% of all greenhouse gas emissions. Moving away from animal agriculture altogether is not required but bringing it back within the limits of nature is necessary and will require major changes. Are these necessarily going to be painful for farmers?

Farmers involved in tillage (cereal grains such as barley and oats) and horticulture (the growing of fruit and vegetables) have been under similar strains to other sectors. Yet these plant-based systems are not free from environmental impacts. Cereals are typically grown to feed animals rather than people and so are an inefficient use of land. Fields in tillage, where soil is ploughed or left bare over the winter months, are sources of carbon dioxide and sediment run-off while degrading the biology of the soil. The sector is heavily dependent on the use of chemical sprays such as the herbicide glyphosate, without which tillage farmers say they cannot operate.

The IPCC recommends the use of no-till systems (i.e. using alternatives to ploughing when sowing crops) and planting cover crops (plants which can be sown straight after harvesting the main crop, thereby covering any bare soil, reducing erosion and adding carbon back to the soil through photosynthesis). There are a number of farmers in Ireland already following this advice (see www.baseireland.com).

Fruit and vegetables grown in Ireland should have a bright future. When I visit Con Traas at his orchard in Cahir, County Tipperary I find him surprisingly upbeat considering the generally gloomy pall which has descended on the farming community.

“Horticulture in Ireland is nearly as valuable as the sheep and tillage sectors put together,” he tells me (and later sends me the figures to prove it). “But it should be a lot bigger. We currently import 95% of our apples but we could be growing half of them here. Also, Ireland is ideal for crops like celery, onions and potatoes but we nevertheless import a lot of these crops”.

Con helped to set up the Horticulture Industry Forum in 2014 to represent the sector’s interests. He tells me that the big supermarket chains control 90% of the retail market and use this bargaining power to squeeze margins to the bone. This means cheaper food for consumers but much of this is being sold below the cost of production, a tactic used by the supermarkets to lure shoppers through the doors.

“This totally undermines the value of the food we’re producing, discourages investment or new entrants and ultimately is a threat to our food security” Con says.

The low profit margins made by fruit and veg growers have left them vulnerable to weather extremes and Con worries about the impacts climate disruption will have on his orchard. In 2018 he lost 20% of his crop after a particularly fierce storm hit right at harvest time. In 2015 the Horticulture Industry Forum highlighted that unless the issue of below-cost selling was addressed, Ireland’s capacity to sell fruit and veg will be “seriously diminished”. The forum called on the government to implement a ‘National Food Policy’ noting that much of our food is imported, sometimes from considerable distances and which leaves us vulnerable to food shortages.

When defending Ireland’s export-driven and environmentally ruinous food production model, the government and the large farmer representative bodies frequently cite its contribution to global food security. They are often heard quoting United Nations projections on population increase – currently 7.8 billion – but expected to rise to 9.8 billion by 2050.

There’s no doubt that feeding the world while maintaining a habitable planet is the greatest challenge faced by humanity. Yet the global food system is riven with inequality. According to an editorial published in The Journal of Sustainable Agriculture in 2012 we were at that time producing enough food for 10 billion people yet the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) says that the number of undernourished people has been rising since 2014.

The FAO said that, in 2017, 821 million people did not have enough to eat. The authors of the editorial were emphatic that “hunger is caused by poverty and inequality, not scarcity… In reality, the bulk of industrially produced grain crops […] goes to biofuels and confined animal feedlots rather than food for the one billion hungry. The call to double food production by 2050 only applies if we continue to prioritize the growing population of livestock and automobiles over hungry people.”[vii]

They argued that agro-ecological methods, such as organic and/or regenerative production models, hold the key to feeding the world. The Irish industry/government drive is doing nothing for global food security and is, in fact, undermining our own food security by creating a production model that is increasingly reliant on imports and one which is vulnerable to disruptions in fragile distribution systems. For example, in 2008, 42 countries banned food exports in order to secure their own supplies – something that is likely to become more common as the effects of global heating intensify.

A 2019 article in the influential journal Foreign Policy declared that climate collapse “will rip the heart out of [Asia’s] food system, leaving 800 million people in crisis. And that’s just Asia. In Iraq, Syria, and much of the rest of the Middle East, droughts and desertification will render whole regions inhospitable to agriculture. Southern Europe will wither into an extension of the Sahara… intensive droughts could turn the American plains and the Southwest into a giant dust-bowl”.

The other main defence of the status quo in Ireland is that we are very efficient producers of beef and dairy and, as demand is rising for these commodities, it is better to produce them here than elsewhere. It is true that demand is growing in places like East Asia even if meat consumption has flattened off in the West. However, our relative efficiency is completely irrelevant when faced with the absolute limits of greenhouse gas concentrations, water pollution and mass extinction.

Indeed our use of the land, in prioritising livestock over other forms of food, or land solely for biodiversity, is notably inefficient. The current system does not even have the benefit of claiming that it is delivering for farmers, many of whom are increasingly disillusioned and/or broke.

Globally, livestock provide just 18% of calories but take up 83% of farmland

Con does not fall into this category. His orchard near the River Suir has been growing apples, pears, plums, sweet cherries, strawberries and raspberries since 1968 when his parents moved to Ireland from Holland.

Since the early 1970s they’ve had a shop on the farm, selling their produce directly to customers, including an apple cider which – I can confirm – is delicious (see www.theapplefarm.com). As well as the shop they run a campsite during the summer months and Con is happy with prices he gets from his larger customers, including the Dunnes Stores chain, which he says is willing to pay a premium for Irish-grown apples.

Over a slice of apple tart, Con and I talk about how a carbon tax on food might make locally grown fruit and vegetables more competitive while Con suggests that a nitrogen tax might encourage better soil management and reduce pollution. Although the below-cost selling of food has been repeatedly highlighted as an issue for Irish growers, this has so far not gained any traction with governments.

In 2017 Ireland imported 72,000 tonnes of potatoes, 47,000 tonnes of onions, 29,000 tonnes of tomatoes, 23,000 tonnes of cabbage and 15,000 tonnes of lettuce valued at €175 million. If we are to shift to more plant-based diets surely the decline of the horticulture sector at once is problematic but also presents an opportunity for Irish farmers?

—

Eating is a political act, and politics does much to shape our food system. If we want changes to the way in which we farm, it will have to come from politicians. So no analysis of Irish farming can be complete without talking to one.

In fact, I get to speak to two – Pippa Hackett is a Green Party senator from County Offaly while her husband Mark is a councillor on Offaly County Council. They are also organic farmers and have big ideas for what needs to happen to change farming in Ireland.

“Consumers don’t know where their food comes from. Many farmers don’t know where their food comes from… very few farmers today even eat their own food” Pippa laments.

Pippa and Mark rear cattle and sheep on their land. They went organic as it was in keeping with their environmental ethos while a government scheme also means an extra €10,000 a year.

In 2015 Ireland had the third lowest level of farmland in organic production in the European Union. At around 2% of land area, it was nearly 10 times less than Austria (at 19%) and well below the EU average of 6.2%.

Pippa, who was appointed as a ‘super junior’ minister for Land Use and Biodiversity in 2020, told me that Ireland should be aiming to have 20% of our land in organic production by 2030.

“We are only putting about €10 million per year into organics at the moment” she told the Irish Independent newspaper early in 2020, “it’s pathetic”. “The bottom line on the Green Party’s vision for agriculture is that we have to embrace nature in everything that we do” she added, noting that the agricultural strategies of recent governments have been ‘disastrous’.

A common mantra is that ‘farmers can’t be green if they’re in the red’ and I ask Pippa and Mark if it is possible for farmers to make a decent living while farming in an environmentally-friendly way.

“Absolutely,” they chime. “Since going organic we have seen our veterinary costs decline because we have healthier animals, we spend nothing on artificial fertilisers or chemical sprays and we get a premium price for the beef and lamb we’re selling. There’s no doubt farming can be economically viable while protecting nature”.

The Green Party want farming to diversify, with an emphasis on growing more fruit, vegetables, grains and nuts here in Ireland as well as ensuring livestock are fully pasture fed. Currently in Ireland we do not grow enough grass to feed all our farm animals, meaning supplementary feed has to be imported. A 2018 report by international NGOs highlighted how soy imported chiefly from South America to the European Union as feed for chicken, pigs and cattle is driving deforestation, wild fires and human rights abuses.

We also have a growing number of feedlots here, where cattle are housed indoors permanently, including systems where animals are fed on grass which has been freshly mowed – technically still being ‘grass fed’ but never actually entering a field. Pippa feels we need greater connection to our food.

“Every town should have a market to allow farmers to sell locally produced food straight to customers. We could make it tax free for people to rent land for horticulture or provide tax relief to those who are eating food they have grown or reared themselves”.

Pippa and Mark’s farm is not only producing beef and lamb. They rear foals, have a pen with free range chickens (all the eggs are sold locally) while also growing pear trees and raspberries. Pippa’s excellent pear chutney (which she gifted me after my visit) lasted all of three days in my house.

But ultimately this is a political battle. “The less is more argument is a hard sell,” she concedes. At a meeting organised by the Irish Farmers’ Association, where she was one of the only women speaking, she was booed by sections of the crowd after announcing she was from the Green Party. But she adds, people approached her afterwards to distance themselves from the booers.

“I also get lots of people calling with ideas… there are a lot of farmers out there who know the system isn’t working”.

When I visited Pippa and Mark’s farm in January 2020 they were gearing up for a general election in which Pippa was hoping for a Dáil seat. She has already done a lot in changing perceptions of the Green Party as being one that is solely focused on urban issues – some farmers were even saying they’ll vote for them, something unthinkable until recently.

Pippa ultimately didn’t win enough votes for a seat but polled strongly in an election which saw the Green Party surge to its strongest performance ever (with 12 seats). She remains a senator and was appointed as Minister for Land Use and Biodiversity in the Department of Agriculture in the new administration. Her message can only become more relevant with time.

If we are to do anything to save dying species like the freshwater pearl mussel, it quickly becomes apparent that we need to change everything. The mussels, with their complicated life cycle and demand for ridiculously high standards of water quality, are not making it easy for themselves. Yet they are also pointing to how far we have drifted from a natural system that allowed them to flourish for millennia.

Many farmers are seeing that major changes are on the way and are correct to be pointing at the low cost of food as being directly linked to their wages and the costs associated with meeting tighter environmental regulations.

A study in the journal Nature at the end of 2020 found that were the costs of greenhouse gas emissions paid for on the supermarket shelf then the price of meat would double and that dairy products would be 75% more expensive.

Agriculture is the biggest source of greenhouse gas emission in Ireland (Image source: EPA).

A kilo of Irish mince in the supermarket that today costs just over €7 would be more than €14 while a litre of milk would rise from €1.24c to €2.36. In this study, the benefits of organic meat production did not come out significantly better than conventional forms of farming. Although organic systems are clearly better for nature as they cut out the use of chemicals, they can do little to reduce the emissions of methane from animals, and that is still the biggest source of greenhouse gases from Irish agriculture (65% of the total). This highlights the inescapable link between cattle numbers in Ireland – over 7.2 million in June of 2020 – and emissions, which need to reduce by 55% by the end of this decade.

Meanwhile, Netflix films like ‘Kiss the Ground’ have brought much needed attention to the health of our soil and the capacity of farming landscapes to remove carbon from the air. But measuring this is complicated and gains are easily lost if somehow land management reverts to industrial techniques. Are customers prepared to pay double the price for animal-based food?

What effect will droughts and extreme weather have on our ability to produce food in Ireland?

It’s not the cow, it’s the how… but it’s also the how many

In a report released by the Drawdown Project at the end of 2020 on the topic of farming and climate change, the authors highlight that there is “no silver bullet”[viii]. They concluded that:

“We strongly endorse approaches that focus both on immediate emissions reductions from the Farming and Land Use sector and long-term investments in regenerative agriculture that can advance farming practices, significantly improve local environmental conditions and soil resilience, and create substantial carbon sinks that can also help address climate change.”

In my research for this episode I came to the conclusion that yes, we can save the save the freshwater pearl mussels, and we can do it without going hungry or putting farmers out of business. We can imagine millions of mussels once again carpeting the riverbeds of the Suir, the Blackwater and the Barrow, in a landscape with beef and dairy cows, barley and oats, apples and carrots, hedgerows and native forests.

But to do it, we need a revolution in how we farm. This will include putting farmers and people back at the centre of our food policies. And we don’t have very long to do this. The mussels live for a very long time, but they don’t live forever.

Artwork by: Jacek Matsiak

[i] Lucey J. 2005. The Irish Pearl. Wordwell Ltd.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] NPWS. 2019. The Status of EU Protected Habitats and Species in Ireland. Volume 3: Species Assessments. Unpublished NPWS report. Edited by: Deirdre Lynn and Fionnuala O’Neill

[iv] Hawken P. (editor). 2018. Drawdown: the most comprehensive plan ever proposed to reverse global warming. Penguin Books.

[v] Stroud J.L. 2019. Soil health pilot study in England: Outcomes from an on-farm earthworm survey. PLoS ONE 14(2): e0203909. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203909

[vi] Slade E.M, Riutta T., Roslin T. & Tuomisto H.L. 2016. The role of dung beetles in reducing greenhouse gas emissions from cattle farming. Sci Rep 6, 18140 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18140

[vii] Holt-Giménez E, Shattuck A., Altieri M, Herren H. & Gliessman S. 2012. We Already Grow Enough Food for 10 Billion People … and Still Can’t End Hunger. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 36:6, 595-598

[viii] Farming our way out of the Climate Crisis. December 2020.