Don’t ask me to be optimistic

As far as apocalyptic weeks go, the one just gone has been impressive. The week started with the publication of a study showing that the rate at which ice sheets in the polar regions are melting is tracking the worst case scenarios which had been predicted in the 5th assessment report form the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, published in 2014. “We need to come up with a new worst-case scenario for the ice sheets because they are already melting at a rate in line with our current one” the lead author of the paper was quoted as saying.

The news of the rapid collapse of polar ecosystems quickly moved on to the wild fires engulfing the west coast of America. Social media filled with eerily orange skies over San Francisco, half a million people are under an evacuation alert in Oregon, while the front page of the New York Times led with the headline: Disastrous wave of climate events slams California. “If climate change was a somewhat abstract notion a decade ago, today it is all too real for Californians fleeing wildfires and smothered in a blanket of smoke, the worst year of fires on record” remarked one of their articles.

Less noticed were the rivers of flood waters flowing through the streets of the Algerian capital or the hundreds of cattle and horses dying in the US state of Louisiana, sucked dry of their blood after swarms of mosquitos appeared from the flood waters of Hurricane Laura (last week’s apocalyptic disaster).

Less noticed were the rivers of flood waters flowing through the streets of the Algerian capital or the hundreds of cattle and horses dying in the US state of Louisiana, sucked dry of their blood after swarms of mosquitos appeared from the flood waters of Hurricane Laura (last week’s apocalyptic disaster).

On Thursday, we opened our news feeds to read the latest report from the World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological Society of London telling us that populations of vertebrate animals have fallen by 68% since 1970. Using words like ‘fallen’ though, do not capture what has happened. This has not been a passive ‘decline’ – better would be to describe what has actually taken place: 68% of the large animals on earth have been exterminated since 1970, a mere 50 years ago. All of the above has been thrown at us since only last weekend.

It’s fair to say that the media here have not engaged with these issues (notwithstanding the excellent work of some journalists) – preferring to stick with what they have decided are more pressing issues, Covid-19 and Brexit mostly. This is despite our own fair share of extreme weather in recent months – from droughts, floods, fires and landslides.

I am often asked if I feel optimistic, but really it would take a special kind of delusion for anyone to feel optimistic after the week that has just gone. But please – don’t confuse this with fatalism. If I were fatalistic, I wouldn’t bother writing this or even turning up for work on Monday. It’s just that I think that optimism is a largely redundant tool for dealing with this crisis. I also think that pessimism is equally useless – none of us can tell what will happen in the future; maybe society will spring into action and act on the science, maybe it won’t. Our job is to do what we can to point out the facts – uncomfortable as they are – and highlight the actions that we feel could and should be taken. I know that other activists do the same.

To cap off the week I’ll probably watch David Attenborough on the BBC present his show Extinction: The Facts, even though I know what’s in it and it will be painful viewing. His aim, they say, is not to try and “drag the audience into the depths of despair… but to take people on a journey that makes them realise what is driving these issues [so] we can also solve them.”

Also this week, we have seen announcements from the government to promote a circular economy and waste reduction, as well as community-based renewable energy initiatives – both really positive steps. There are clear and definite moves towards better public and active transport with real investments being made. When faced with what seems like a wall of dire news, it’s easy to be overwhelmed. But these announcements are vitally important. No one action or policy announcement will bring us to where we need to be, but collectively they will. It will be an on-going process that will probably go on for decades – the ecological emergency is not something that is going to pass within our lifetimes. I’m waiting for the big announcements to alleviate the biodiversity emergency – like the review of the National Parks and Wildlife Service, the designation of marine protected areas, a nature-friendly Common Agricultural Policy or the new Forestry Programme to restore and expand our native woodlands. These have all been promised – maybe they will deliver, maybe they won’t. The vested interests are still there and fighting change tooth and nail to maintain business as usual.

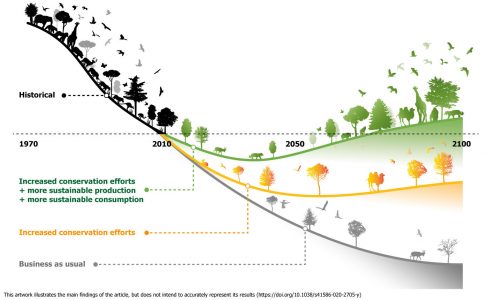

To cap the week off, the journal Nature published a study which modelled possible scenarios to address global biodiversity loss. The work suggested that reducing food waste, reducing meat consumption by 50% in countries with high meat consumption, increasing crop yields, better trade agreements and protecting 40% of land in wilderness or ‘key biodiversity areas’ would see the extinction curve move towards restoration by 2050. They conclude that without dealing with food security, measures to restore biodiversity are unlikely to succeed. Unlike the melting of the ice caps or the incineration of California, this study does not give rise to pessimism. But nor is it a hopeful message. Like all modelling, it is not a crystal ball to tell us what the future will look like. It is simply setting out possible scenarios – options we can take should we choose to. In Ireland, setting aside 40% of our land (and even more of our seas) while shifting farming to low carbon, nature-friendly systems is possible without causing an apocalypse for rural Ireland. If done right, it could address existing hardship in farming sectors while providing new opportunities for businesses.

Model scenarios from research published by ‘Nature’

Am I optimistic that this will happen? Of course not, why would I be? This vision is met with howls of protest and there are few people selling it. Most politicians and media have not engaged. But the path is there. The EU’s Biodiversity and Farm to Fork strategies, combined with the Green New Deal show the way. We are living in a period of unlimited free money – the government can borrow pretty much as much as it wants, to do what it wants. Despite a rocky start, I still believe that a government with the Green Party in it is better than one without it. For many this is a source of real hope – and if I see the big things happening I will probably feel hope myself. Until then, don’t ask me to be optimistic.