I am the wind which breathes upon the sea,

I am the wave of the ocean,

I am the murmur of the billows,

I am the ox of the seven combats,

I am the vulture upon the rocks,

I am the beam of the sun,

I am the fairest of plants,

I am the wild boar in valour,

I am the salmon in the water,

I am a lake in the plain,

I am a word of science,

I am the point of the lance of battle,

I am the God who created in the head the fire.

Who is it who throws light into the meeting on the mountain?

Who announces the ages of the moon?

Who teaches the place where couches the sun?

(If not I)

If everything needs to change then where can we begin? How far back do we need to go to get at the root of our troubled relationship with the planet? “Very far back” says Sister Colette Kane of An Tairseach Ecology Centre in Wicklow Town.

It’s a bright January morning in 2019 when I meet Sr Colette in the Ecology Centre and organic farm high above the tangle of narrow streets below. Situated within an enormous red-brick Dominican Convent and school which was established in the 1870s the building, at least, seems to typify the Catholic Church in Ireland at that time – looking down on the community, imposing and overbearing.

Not at all like the softly-spoken, kind-eyed Sr Colette who started work at the centre in the early 1990s. She leads me to the centre’s cosmic garden for a tour of the story of the universe. Yes – these nuns have a cosmic garden!

The garden, converted from a tennis court only a decade earlier, is now enveloped with vegetation and at its centre lies a stone spiral; beginning at the Big Bang the visitor is invited to contemplate the deep history of time, following the path in a gently arcing clockwise direction, stopping at intervals to admire the hand-painted stones that punctuate the journey. There’s one which marks the creation of the Earth, another (much later) to indicate the earliest known life form, and on to multi-cellular life, the emergence of life on land, the extinction of the dinosaurs and – all bunched up at the end – the evolution of humans and their headlong rush to industrialisation, symbolised by a row of smoke stacks spewing out the by-products of our civilisation.

It’s not how Creation is understood in the Bible. “Misinterpretation of some passages in the Bible has a lot to answer for,” asserts Sr. Colette, who grew up in Belfast during the Troubles. She saw how gangs of youths pulled trees out of the ground to create barricades – wilfully destroying their own environment.

“I couldn’t understand why they would do such a thing” she laments. She believes our Christian heritage, with its origin story rooted in the Book of Genesis, continues, to this day, to be misrepresented.

For some the concept of ‘dominion’ gives us licence to destroy nature. It is the line:

Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.

(Genesis 1-28, King James Bible)

in particular which allows us to treat the non-human world like a larder from which we can take what we will, without feeling we should give anything back.

To those who feel this is far-fetched, I refer you US President Donald Trump’s first head of that country’s Environmental Protection Agency, Scott Pruitt who, before he resigned in scandal, told the Christian Broadcasting Network that “the biblical world view with respect to these issues is that we have a responsibility to manage and cultivate, harvest the natural resources that we’ve been blessed with to truly bless our fellow mankind.”

According to this philosophy, ignoring climate change and even opening national parks to fossil fuel exploitation is not only right, it is a duty among elements within the Christian Right.

Since at least 1492, when Christopher Columbus set foot on the American continent, God and Jesus have been used to create the morally righteous space in which people and nature have been remorselessly exploited for profit.

Sr. Colette points me to ‘the Great Chain of Being’, a visual representation of the universal order believed, in medieval Europe, to have been decreed by God. It places God above all else, followed by the angels and other angelic beings. Beneath this lies humanity, itself differentiated between kings above the peasants and men above women. Animals were subdivided between (superior) wild and (inferior) domestic varieties, with hierarchies within these groups to prioritise the useful and beautiful over the useless or ugly. Then came the plants, beneath all these were the serpents, especially condemned for tempting Eve into bringing evil to the world, and then the minerals.

The Great Chain of Being: an idea that entrenched human dominance of nature

The ‘Great Chain of Being’ entrenched a Western, white, male-dominated, exploitative world view which has spawned atrocities since the 1500s – from slavery to logging ancient forests – and which continues to convulse the world to this day.

By the 17th Century science was beginning to erode the dominance of the Church. The birth of rationalism and the Enlightenment brought answers to questions not found in the Bible. Yet this did not include what we would today consider to be a more enlightened attitude to nature.

The influential French philosopher René Descartes proclaimed that the creatures of the Earth were no more than machines, incapable of feelings or reason, and so inferior to humans. The natural world, it was fashionable to believe at the time, was like a clock – composed of moving parts all running like a toy, wound by the hand of an almighty creator.

René Decartes, for whom plants and animals were no more than machines

This coincided with the idea of progress, the view that wild nature was degenerate and could only be improved by an axe, a plough or domesticated animals. It seeped into our art, the notion of ‘picturesque’ reflected in landscape paintings that portrayed ordered, domesticated and subdued countryside as ‘beautiful’ and worthy of depiction. This infuses our mindset to this day – just look at the popularity of the ecologically-moribund ‘Wild Atlantic Way’.

The corollary of all this is that nature – not tamed by the hand of man is useless, or even worse: threatening. It explains why top predators are dismissed as ‘vermin’, unwanted plants as ‘weeds’, why we find it so easy to launch culling or eradication programmes for species we find inconvenient or even why we can bulldoze an ancient forest or drain a bog for the sake of jobs or ‘economic development’.

In the early 1800s the Prussian adventurer Alexander von Humboldt, after blagging a visa from the King of Spain to enter the Spanish colonies of South America (then off-limits to nearly all non-Spaniards), found himself heading up the Orinoco River (in today’s Venezuela) in a canoe with his botanist companion Aimé Bonpland.

Alexander von Humboldt, who saw everything as interconnected and part of a unified whole

Searching for a connection between the Orinoco and the Amazon the two explorers collected samples and made maps of heretofore uncharted terrain. But it was von Humboldt who would excel himself in his insatiable appetite for knowledge and understanding. There was no field of endeavour which escaped his analysis. From the movements of the heavens to the appalling treatment of slaves on the colonists’ plantations he began to see the world, not as the rationalists would have it – as cogs in a machine – but as an infinitely complex web of connections. He decried how the imperialist Spaniards treated the indigenous peoples but at the same time noted how their subjugation of wild nature, and in particular the clearing of the rain forest and the draining of lakes, led to flooding, drought and even changes in the climate.

He sketched zones along the slopes of Andean peaks, remarking how changes in vegetation could be correlated with temperature, and even noted how wind carried pollen particles, insect eggs and seeds to colonise distant places. After descending Ecuador’s highest volcano, Chimborazo, he drew out what he called his Naturgemälde, an untranslatable German term meaning ‘painting of nature’ but which implies a sense of wholeness or unity[i].

It is why he has been called the ‘Inventor of Nature’. According to his biographer Andrea Wulf: “Humboldt was not so much interested in finding new isolated facts but in connecting them. Individual phenomena were only important ‘in their relation to the whole’”. His ideas were revolutionary and he was to become Europe’s, if not the world’s, most famous and celebrated scientist.

He decried the mechanistic view of nature and the belief that the classification of life forms into compartments (which had been underway in earnest since the Swede Carl Linnaeus proposed his universal system of naming life in the mid-1700s) was the pinnacle of natural science. Instead, he argued for the centrality of wonder, poetry, song and imagination in the sciences in his book Views of Nature.

The English poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge were fans, the latter declaring that they lived in a ‘epoch of division and separation’, blaming philosophers such as René Descartes and scientists such as Carl Linnaeus for their ‘philosophy of mechanism’ which ‘strikes Death’. Wordsworth sneered at the naturalist with his urge to classify as a “fingering slave, one that would peep and botanise upon his mother’s grave”[ii].

According to Wulf, Coleridge and Wordsworth were ‘turning against the idea of extorting knowledge from nature with ‘screws or levers’ […] and against the Newtonian universe made up of inert atoms that followed natural laws like automata. Instead, they saw nature as Humboldt did – dynamic, organic and thumping with life.

In 1869, one hundred years after his birth, Alexander von Humboldt’s centenary was marked by parades and celebrations across the world. From Melbourne to Moscow, San Francisco to Cape Town there were speeches and parties to honour the contribution he had made to science. A crowd of 25,000 thronged Central Park in New York to witness the unveiling of a bronze bust, while then-US President Ulysses Grant joined 10,000 devotees in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to celebrate the great man. To this day his name is sprinkled across the maps of North and South America, giving his name to rivers, towns, ocean currents and even a species of penguin.

His work directly inspired Charles Darwin who carried his books on board The Beagle and echoes of his thinking are found right up to James Lovelocks’ Gaia hypothesis, which proposed that the Earth was a single living system. He practically founded the science of ecology and, in his rejection of slavery and promotion of human rights, as well as his view that art was an essential medium for the understanding of scientific concepts, his views retain their relevance to this day.

In Wulf’s view, the advent of war in 1914 radically shifted public attitudes to Germany and Germans, instilling prejudice and negativity that would not begin to dissipate for another 50 years. By this time von Humboldt had been largely forgotten in the English-speaking world and his mantle as ‘the Inventor of Nature’ passed to an Englishman, Charles Darwin.

In the decades that have passed since, science has become ever more specialised and fragmented and scientists themselves continually decry the entrenchment of ‘silo thinking’ whereby people rarely discuss matters beyond their own tiny niche of investigation. Media reports can segue from a story on climate change to cheery projections of economic growth in the airline business without a hint of irony. Irish discussions of agriculture can talk about greenhouse gases without connecting production intensification with the extinction of species, water pollution or income inequality among farmers. Tourists can gush about the natural beauty of the landscape unconcerned that they’re looking out on a collapsed ecosystem. We have lost the ability to join the dots.

Sr Colette leads me through the main hall of An Tairseach’s (meaning ‘threshold’ in Irish) ecology centre – in an alcove there’s a beautifully sculpted Celtic cross, hewn from wood, with roots extending from the base of the cross to symbolise the life-giving connection between spirituality and nature. The centre was established in the 1990s by the Dominican sisters.

They had 70 acres of farmland but could see the damage that modern farming techniques were doing to the land, so they set about reclaiming it and converting it to organic production. Today there is a small herd of cattle, a few pigs and about five acres of organic vegetables apart from what is grown in six large tunnels. The farm provides vegetables and meat for the Ecology Centre as well as for sale in the Farm Shop and at a number of markets around Dublin.

While on my tour we bump into Sr Julie Newman and Sr Marian O’Sullivan, two of the founders, who happily recall the journey they have been on. They tell me how during the Celtic Tiger years local politicians tried very hard to get them to sell the land for housing. The community resisted all inducements because they had made a decision to preserve the land for the conservation of wildlife as well as for organic food production.

The local community were delighted that the land was being preserved and helped in many ways including with the planting of trees. “Nature has a right to exist” the sisters told me and, raising an index finger towards the heavens – “it has rights!”

Values are at the heart of their ethos: ‘truth and fairness in relationships’, ‘respect for the whole community of life’, ‘graciousness to all who come’ and ‘beauty in all its dimensions’. And so their project goes much further than organic farming. They were a pioneer user of solar panels to generate electricity and have set aside land that is only for nature.

Sr Colette insists that education is the key to reversing the mentality that has allowed centuries of over-exploitation. Since their establishment they have been running courses in ecology and what might be called ‘ecological spirituality’ including retreats for those who wish to immerse themselves in the reflective space provided by the centre.

They have been running a specially designed programme called ‘Knowing Our Place: from stardust to sand’ for teachers and Sr Colette has noticed an uptick in interest in recent years. Yet she laments the slow pace of change. Even the ‘Green Schools’ programme, which has been running for years, while it is “a positive attempt at raising awareness of sustainable living is not nearly ambitious enough for something as important as our relationship with nature”.

I have to admit that I was unfamiliar with the work of An Tairseach until I started researching this project and it came as somewhat of a surprise to me that there were religious institutions in Ireland thinking in this way.

Like many of my generation, I had decided some time ago that the Church in Ireland had little to offer and, in my own bubble of interacting with ecologists and NGOs, I had assumed that if there were movements out there fighting for greater environmental protection then I’d surely know about them. I was wrong.

I returned to the centre later in the year to hear from Fr Sean McDonagh, a Columban priest and eco-theologian. He worked in the Philippines and spoke about how deforestation there has been combining with stronger storms caused by climate change leading to mudslides, flooding and the destruction of farmland in communities already wracked by poverty. Yet people didn’t seem to see the connections.

Fr Sean has been writing about the ecological crisis since the 1980s yet he is clearly not impressed with the tardiness of the Church in joining the dots been human welfare and environmental degradation. During his seminar he name-checks various Popes and their pronouncements which failed to recognise the severity of the issue.

Deforestation is not only habitat loss, it leads to soil erosion, water pollution and can change local climates

He references a publication from the World Council of Churches back in 1994 entitled ‘Signs of Peril – Test of Faith’ and which began to develop what he described as a ‘theological and ethical framework to help them understand the implications of climate change for their faith’[iii]. Yet the Vatican maintained, in his words, a “general reticence”.

That same year, for instance, the Catholic Catechism stated that “God willed creation as a gift addressed to man… Animals, like plants and inanimate beings, are by nature destined for the common good of past, present and future humanity”[iv].

Fr Sean knows his stuff, and he’s been talking and writing about it for a long time. He tells our small seminar that “we’re destroying the beauty and wonder of our planet”. He says that while we can see the damage we’ve done to our land, it’s unfortunately invisible in the oceans but, he adds “World War II ended in 1945 on land, but it has continued at sea”.

He clearly carries the weight that many ecologists feel in that the warning signs, which are so plain and obvious to us all, continue to be ignored. “There’s a great need for education aimed at all sectors of society… including ‘ecological theology’ in Catholic schools, seminaries and theological institutions”.

In 2015, Pope Francis published his encyclical Laudato Si: On Care for our Common Home. Although (to my regret) I paid it little heed at the time, when I did get around to reading it I found it to be the most powerful piece of ecological writing I had read in years.

Both Sr Colette and Fr Sean agree that it is a quantum leap in Church thinking, and because the Pope addresses the encyclical to “every person living on this planet”, you don’t have to be a Catholic to be inspired by it.

In it the Pope is blunt about the current state of affairs:

..our common home is like a sister with whom we share our life and a beautiful mother who opens her arms to embrace us… [but] this sister now cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her. We have come to see ourselves as her lords and masters, entitled to plunder her at will. The violence present in our hearts… is also reflected in the symptoms of sickness evident in the soil, in the water, in the air and in all forms of life.

Finally, we’re beginning to join the dots again. Not since Alexander von Humboldt have the connections between science, art and ethics been so skilfully woven:

“If we approach nature and the environment without this openness to awe and wonder, if we no longer speak the language of fraternity and beauty in our relationship with the world, our attitude will be that of masters, consumers, ruthless exploiters, unable to set limits on their immediate needs.

It is this sea change in our values which is surely at the heart of our current predicament. The Pope fudges the whole Genesis ‘dominion’ thing and although it has taken over 2,000 years for this to be corrected the Pope makes up for it in his force and clarity.

“It is not enough to think of different species merely as potential ‘resources’ to be exploited, while overlooking the fact that they have value in themselves. Each year sees the disappearance of thousands of plant and animal species which we will never know, which our children will never see, because they have been lost for ever. The great majority become extinct for reasons related to human activity. Because of us, thousands of species will no longer give glory to God by their very existence, nor convey their message to us. We have no such right.”

To me, it is this talk of ‘values’ and ‘rights’ that holds the key to the transformation that is needed.

The Pope writes that he is convinced that “change is impossible without motivation and a process of education”.

Writing in the ‘Irish Response’ to Laudato Si, Fr Sean McDonagh asks himself: “will this transformative education happen? Will humans turn from being ‘masters, consumers and ruthless exploiters’ to feeling ‘intimately united to all that exists?… I am convinced that without serious reflection and education at an individual and community level Laudato Si will be ineffective, because what is called for here will involve massive changes.”

He later remarked to our seminar how he had attended a national conference on biodiversity earlier in the year but was astounded that amid all the sessions on conservation science and economics, there wasn’t a single mention of ethics. “How can we change things without challenging our ethics?” he pondered, rhetorically.

Faced with the remorseless advance of the global economic juggernaut, making these massive changes can seem daunting. However, they’re not beyond reach. All human cultures possess value systems which provide the ground rules for cooperation. In the absence of laws and law enforcers, values have provided human societies with a means for maintaining cohesion and resolving conflicts.

Today we broadly accept that historic buildings should not be demolished even if the land is valuable from a development perspective, or that mining for minerals in scenic areas is a bad idea (even if occasionally such projects are proposed). We mostly agree that robbing and stealing are bad, not only because they are themselves morally wrong, but because we all benefit when such norms are widely accepted and enforced.

And values are not immutable – once a central part of many companies’ business models, today human slavery is outlawed everywhere (although practised furtively). Polite conversation no longer permits talk about black people or women in the way white males felt at liberty to do until quite recently (even if they still hold the thoughts in their head while social media seems to be no holds barred).

In Ireland, in only the last five years, public attitudes to gay marriage and women’s reproductive rights flipped in a dramatically short space of time. Nobody talked about economics during these debates. It is why I find that trying to shoehorn nature into the world of economics via terms such as ‘ecosystem services’ and ideas of ‘natural capital’ are all wrong.

Economics needs to find its place in the biosphere – not the other way around.

Human rights, including the rights of gay people to marry, or for women to make their own decisions concerning their bodies, are now enshrined in law.

Laws tend to follow our values (although not always) as, particularly in modern societies, they are necessary in upholding people’s rights in the face of opposition. However, the reverse is not the case – values do not follow laws.

This is where we have been going wrong since the 1970s – despite the raft of environmental legislation (see episode 2), nobody feels particularly compelled to see these enforced, and so nature continues to vanish.

It’s over 70 years since Aldo Leopold wrote about what our environmental values should look like. Born in the US state of Iowa in 1887, he was forever what Americans refer to as an outdoorsman – hunting, fishing, camping and perpetually observing nature.

He studied forestry and was instrumental in establishing the United States’ first wilderness area (a term which has legal standing in that country) in New Mexico in 1924. He was assigned to shooting large predators such as mountain lion, bears and wolves which were considered no more than vermin to ranchers who had recently moved into the area.

But he developed a respect for these top predators, something which progressed to seeing them not only as having a right to exist, but as essential for the health of the ecosystem as a whole. He saw nature as something that was not just there to provide humans with benefits but as something that had intrinsic values.

He was a founder of the Wilderness Society in 1935 but it was his writings that gave his work a legacy which lasts to this day.

In A Sand County Almanac he writes about a plot of land in Wisconsin he had purchased. The landscape had been badly degraded from ploughing the prairies, felling the forests, degrading the soil, wild fires and overgrazing the pastures with herds of domestic cattle. The big predators had been exterminated.

In the book, published in 1949 just after his death, he elaborates on what he refers to as ‘the land ethic’. It is a manifesto for a relationship with land that goes beyond limitless exploitation. The ethic, which now extends across the human family, must now, he opined, encompass the land under our feet, what he referred to as ‘a process in ecological evolution’.

“An ethic, ecologically, is a limitation on freedom of action in the struggle for existence. An ethic, philosophically, is a differentiation of social from anti-social conduct.”[v]

It is this idea of limits which is so anathema to mainstream economic and political thinking. It also explains why creating another nature reserve or extolling the virtues of recycling will not, on their own, result in the changes we need to see.

Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac sold over 2 million copies and remains the most influential text when it comes to environmental ethics. Yet it had no impact on what has come to be known as ‘the Great Acceleration’ – the exponential increase in extraction and resource use which has broken through so many of our planetary boundaries.

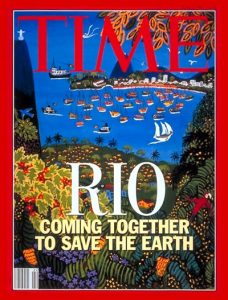

1992 was a landmark year for Planet Earth with the holding of the Rio Earth Conference in June of that year. “Coming Together to Save the Earth” proclaimed the cover of Time magazine: “tens of thousands of diplomats, scientists, ecologists, theorists, feminists, journalists, tourists and assorted hangers-on… If size and ambition were the measures of success, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro would take all the prizes. The so-called Earth Summit, more than two years in the making, will be the largest and most complex conference ever held — bigger than the momentous meetings at Versailles, Yalta and Potsdam.”[vi]

The Earth Summit, where great promises were made

Our own President Michael D. Higgins was present at that gathering, and he spoke of his reflections of the event at a conference in Dublin early in 2019:

“1992 represented such a hopeful juncture when it seemed that the world was finally coming together to address the existential challenges of our age… and while there have been some notable advances to this end, I think it is fair to say that the agenda of work recognised then is far from complete.”

He recalled the Business Council for Sustainable Development (BCSD), which was established at Rio and included at that time 48 CEOs and how they were the ‘most sophisticated people’ he interviewed for a documentary he was making at the time. Delegates leaving the summit were left asking, he said “[if this meant] that the BCSD were going to initiate a whole new wave of changes in relation to the impact of irresponsible corporations on the environment and vulnerable parts of our planet”.

This gave him hope but he recalled how others travelling with him could see how the business leaders recognised that the word ‘sustainable’ would now be unavoidable and were set to “colonise the new language”.

He went on lambaste these businesses as the “same corporations that said to peasants in Ecuador whose water was poisoned: we will fight you until hell freezes over, and then we’ll fight you on the ice, with armies of lawyers, ranged against peasants who were representing their village and the children who would be born in it for generations to come.”

I was there to watch the President deliver these words and it electrified the crowd. The previous day, the Minister with responsibility for nature conservation, Fine Gael’s Josepha Madigan, told RTÉ news that people could put up bird boxes to tackle the extinction crisis.

The President’s uncompromising call for entire system change, acknowledging that “if we were miners, we’d be up to our knees in dead canaries” brought cheers and a standing ovation – if only because he could recognise the scale of the problem and its insidious roots.

President Higgins – he gets it

Our world is essentially a white, male, Western one. To most of us it is synonymous with wealth creation, technological innovation, cultural riches and progress. Since the conquest of the Americas in the 1500s it is a model that has been exported, by force, to every corner of the world. To the colonised and displaced peoples (with whom Irish people share a legacy) this world is synonymous with an altogether different set of values. It is hard for those of us who live in this bubble to break through the barriers to hear their voices, because in many cases they’ve been dispossessed of them.

Take the song, ‘This Land is Your Land’ by Woodie Guthrie. It was written in 1940 in response to the gaping inequalities created during the Great Depression of the 1930s and includes the lines:

This land is your land, this land is my land

From California to the New York Island

From the Redwood Forest to the Gulf Stream waters

This land was made for you and me

It was meant as a riposte to ‘God Bless America’ and has become an anthem for Americans with liberal politics, including environmentalists. The song is one of the most popular in American folklore for its political message of solidarity with the oppressed and downtrodden.

But not everyone sees it that way.

In 2017, during a climate march for Earth Day in Washington DC, black climate activist Mary Annaïse Heglar found herself in the centre of a predominantly white throng when the crowd erupted in song.

She describes herself as a ‘black woman in a green space’, from Birmingham, Alabama and instinctively reluctant to join large, white crowds. In hearing the opening line of ‘This land is your land’, she says she felt her stomach ache.

The song evokes the landscapes of America but for Heglar, “there is not a single verse that I, as a Black woman, can relate to, not one that speaks to my experience nor my complicated relationship to the land on which I stand”.

For the founding fathers of America, who subjugated minorities while at the same time creating national parks and wilderness areas, “it was less about protecting nature than it was about laying claim to it—for people who looked like them.”

“In today’s environmental movement” she wrote for Dame Magazine “it’s not so much outright hostility toward people of color. It’s more that people of color represent a blind spot for the environmental movement.”

She later took to Twitter, on Earth Day in 2019, to explain why she got involved in the environmental movement:

“Ever since I got involved in this space… it became real clear real fast why the movement was so anaemic. Simply put, the movement was telling itself an incomplete story that rendered people – [especially] people of color – to the margins.

People of color are largely invisible in this color-blind movement. And I don’t know how I’m supposed to feel about that. But I do know how I feel: dismissed, silenced, erased. But also motherfucking determined to make you see me.”

I think that the blind spot Heglar refers to is relevant to us here in Ireland because it prevents us from looking over the brow of the hill, to see that alternatives are possible and that other voices are worth listening to. It is a challenge to a monoculture of thinking.

It’s not only essential that we give voice, and listen to, those of indigenous and non-white heritage, but also the half of the world which has been ignored for most of human history – women.

I meet with Sinead Mercier who is founder of the Dublin EcoFeminists, a growing movement of (mostly women) who recognise the interconnectedness between the exploitation and degradation of the natural world and the subordination and oppression of women.

Sinead explains to me that eco-feminism “is not really about women but about who’s being exploited. The ecofems were set up to campaign on Repeal the 8th and also to address the constant, quite sexist and racist, argument brought up in a lot of environmental circles that overpopulation is the source of climate change, and which inevitably results in blaming and controlling women’s bodies (particularly the bodies of women in the global south.)

This colonial belief in an inherent right to rule over and exploit women, or colonised peoples, is allowed because these sections of society are “othered” from the powerful and then are equated to something we have been trained to denigrate and exploit without respect – nature”.

Our conversation is peppered with recurring themes: work that is not acknowledged, marginalised voices, power imbalances and the mechanisms which have led to the subordination of both women and nature.

There is more than an echo here of the #metoo movement, debates around consent and ‘toxic masculinity’.

Speaking to The Irish Times in 2018, French presidential candidate Ségolène Royal, a woman who went on to serve as environment minister in the cabinet of her former partner François Hollande, was clear in her belief in the connection between misogyny and environmental degradation. “The vocabulary is the same,” she told the newspaper, “Women and nature are damaged, aggressed, sullied, raped, victims of predators, exploitation and abuse”.

It’s a theme that has been picked up here in Ireland by our former President Mary Robinson and comedienne Maeve Higgins in the podcast series ‘Mothers of Invention’ which declares: “Climate change is a man-made problem — with a feminist solution!”

Climate breakdown: A man-made problem… with a feminist solution

Sinead believes that the traditional, male-dominated, approach has led to perspectives of nature as mechanical and this has led us inexorably to today’s separation between people and the land:

“We’re not separate: we’re a part of nature,” she says.

“It’s this false separation which has led us to think we can just take as much as we want. For example, colonialism sought to denigrate and lower other races by connecting them to “wild” or a “passive and exploitable” nature – nature is without a subject and so are women and other colonised peoples. They have to be ruled over and decisions made for them because they cannot rule themselves as they are the mercy of natural passions. How this affects the environmental movement is when we blame poor people for environmental damage as they struggle to survive in the nature that remains after exploitation. The people that ‘save nature’ are white, well-to-do Northern Europeans, not African peoples, indigenous peoples, travellers or small farmers who connect nature to their livelihoods”.

Sinead illustrates the real impacts this has with the example of when, at the World Economic Forum meeting in 2020 in Davos, Switzerland, Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate was edited out of an Associated Press photo with Greta Thunberg and other white student activists. “Media are more comfortable with Jane Goodall’s and white activists than with people from the Global South” she concludes.

“And the reason for this is pretty dark,” she adds. “The belief that overpopulation is the cause of climate change is still so strong and the blame is almost squarely lain at the door of developing countries. Having African climate activists speak out – with their own voice, power and subjectivity – rather than be presented as charitable cases or dangerous wombs – is not something Western media (or to be honest many Western environmental NGOs) are comfortable with.”

Despite our history of colonisation, our attitude to the land and the sea retains much of the extraction-based, exploitative mindset of the white, male settler. We can learn from indigenous peoples even if they don’t look like us or don’t share our history.

Take the Mapuche Nation of southern Chile. They maintained their autonomy right up until the 1880s when their lands were taken by the new Chilean Republic and today they number over one million people.

Their landscape is one of profound beauty, with forests, mountains and great rivers. Their worldview holds that there’s an earthly river – which connects individual tribes and families across valleys, and a spiritual river in the sky (the constellation that Western scientists call the Milky Way) which is a ‘galactic river’ and home to all of their ancestors which have departed the Earth.

The earthly rivers are sacred places, home to plants and animals but also spirits, and anyone wishing to take something from these wetlands and marshes must first ask permission. To pollute a river or damage its fragile habitats is an act of desecration, causing the spirits to flee – something which can only result in sickness and ill health falling on the people.

For the Mapuche, the Río Biobío was their great river which ran through the lives of the wildlife, the people, their dead ancestors and the spirit world. That was until it was dammed in the 1990s with a series of three giant hydroelectric barriers, displacing communities and flooding thousands of hectares of land. This has led to an outbreak of depression, substance abuse and social issues among the Mapuche people.

Their campaign has had more success in recent years and in 2019 Alberto Curamil, of the Mapuche community, won the prestigious Goldman environmental prize for his work in preventing new dams on the Cautín River. At the time I was researching this story, he was detained by Chilean authorities on robbery charges, something his supporters maintain was politically motivated.

As he was unable to accept the prize in person, his daughter, Belén, accepted on his behalf in San Francisco saying: “The Mapuche struggle is an ecological struggle, it is a struggle for life and its continuity… We are people of the Earth, whose main mandate is to protect everything that makes existence possible, based on a spirituality connected with the natural elements.”

“The traditional Western view of rivers — and of nature generally — has failed us. Western legal systems and governments traditionally viewed water and water rights as property, leading to overuse and contamination. One criticism levied by environmental groups is that in countries like Chile and the United States, corporations are granted the same rights as people while the living ecosystems upon which we depend for survival are not”.

So wrote Jens Benöhr, a Chilean anthropologist, and Patrick J. Lynch, an American attorney in an article for the Yale School for Forestry and Environmental Studies. This last point is critical, and it is leading to new movements for the granting of legal rights to ecological features, and rivers in particular.

The article cites developments in New Zealand and India while in 2019 Lake Eyrie in the USA citizens can now sue corporations for pollution as if the lake were a person. But to me, the most eye-catching so far is the case of the Río Atrato in Colombia, whose Constitutional Court granted legal personhood to that river in 2017.

It flows through the Chocó region, a biodiversity hotspot and home to 91 indigenous communities. The ruling gives rights to the river for its protection and, where necessary, its restoration. It obliges the Colombian government to establish the Atrato Guardian Commission which will consist of 14 legal guardians from communities affected by mining and pollution. It is early days, and the people are battling powerful gold mining interests, but they now have an important legal mechanism which enshrines their ethics and values before a court.

Could we see this in Ireland?

Were the River Shannon to have legal rights, citizens could sue the state so that the dam at Ardnacrusha is removed – something which has led to the near disappearance of the river’s fish life. Or a board of guardians could ensure that the peatlands along its banks, which have been stripped away in the last 70 years, are restored and rewilded.

Are rights for nature the missing piece in our legal framework?

Will our values evolve so that such a constitutional amendment would be approved by the Irish people by a similar margin to that for marriage equality in 2015 or abortion in 2018? In fact much work has already been done in this regard.

In the wake of the financial crash of 2009, the government established a Constitutional Convention made up of politicians and ordinary members of the public. It invited the assembly to consider changes under some pre-defined headings but also invited members of the public to submit their ideas, including through a series of public meetings.

I remember attending one of these in Dublin and speaking up for the idea of a right to a healthy environment in the constitution. In the end, this idea won the most support among ordinary members of the public who had made submissions.

Yet the idea was dropped in the final report.

In 2017, the Environmental Pillar (an amalgam of environmental non-governmental organisations in Ireland) called on the Citizens Assembly to include a constitutional amendment among its recommendations.

It had been tasked to develop a plan to ‘make Ireland a leader in tackling climate change’. Although making 13 excellent suggestions in reaching this goal, the Assembly did not view climate change in the wider context of ecological breakdown, and the recommendation was not included.

Donna Mullen, spokesperson for the Environmental Pillar, said at the time “This constitutional approach will yield benefits to our economy, society, and most importantly, health. Already 1,200 people are dying prematurely from air pollution in Ireland each year, with over 150,000 deaths across the globe already attributed to climate change every year”.

I spoke to Donna in 2019 and asked her why she thought the idea had been dropped back in 2009. “It seemed to me that there was political interference. Although the members [of the Assembly] seemed to want it, and certainly the general public wanted it, when you watched the videos of the convention, the public seemed slightly in awe of the politicians, who were adept in public speaking. However, we had great support from some politicians. I noticed that in the next citizens assembly, politicians were excluded.”

I ask Donna why a change to the Constitution would make any difference given that we already have such an elaborate body of environmental law:

“Constitutional protection gives the environment the status it deserves. It would be then on a par with property rights and protections. All new legislation would have to consider the environment and any poor environmental laws or policies could be challenged.

I’ve been to visit a few countries and looked at it in action. One interesting thing is that everyone tells you about the constitutional environmental protection – from taxi drivers in South Africa to tour guides in Namibia – the people feel they have ownership of their environment.”

Already in Ecuador and Bolivia the rights of ‘Mother Earth’ (Pachamama – the Andean goddess of the Earth) are enshrined in the constitution. In Columbia, the ‘collective right’ of the environment has been in force since the early 1990s but as part of this it is recognised that care for nature must be a part of the daily culture of everyday citizens and state institutions – something that has been lost here in Ireland.

These approaches have had mixed success.

In March 2019 I went along to a meeting of the Latin American Solidarity Centre in Dublin where I heard Aldo Orellana López and Gabriela Burnett, both from Bolivia, speak about their home country.

The talk was billed as “Environmental Issues in Bolivia: what do the rights of nature really mean in Latin America’s most indigenous country?”

I trotted along, full of hope that I’d hear about a country from the global south which had turned the tide on Western, corporatist, extractivist economic models of development. Bolivia had been led by its leftist leader Evo Morales from 2006 to his overthrow in 2019 and was the country’s first indigenous president. The Pachamama clause entered their constitution in 2009.

However, as it turned out, this did not draw a line in the sand to protect Mother Earth.

Orellana López and Burnett told us how today 80% of the Bolivian economy is based on extraction, the rate of deforestation increased post-1990 and megadams are planned to quintuple in output.

“Bolivia has the best laws for the protection of the environment and human rights on paper,” they told us. In reality, the government has stuffed the courts with their cronies, and judicial challenges using the Mother Earth law have so far failed. “In Columbia there is a high rate of murder, but you can trust its legal system,” Orellana Lopéz told me flatly when we chatted after his talk.

On an international front, there is a growing movement to include Ecocide as a crime equivalent to genocide or crimes against humanity. ‘Ecocide is defined as serious loss, damage or destruction of ecosystems, and includes climate or cultural damage as well as direct ecological damage.’ It was championed by British lawyer Polly Higgins until her untimely death in 2019 and who was campaigning to include Ecocide in the Rome Statute, so that it would be a prosecutable crime in the International Criminal Court at The Hague.

She described herself as a “lawyer for the Earth”. She wanted to criminalise “mass damage and destruction” which is “of such significance to humanity as a whole that it should stand as an international crime”. It is, she asserted, the ‘missing law’.

There is no doubt in my mind that had such a law existed in the aftermath of World War 2, state-companies like Bord na Móna, the Office of Public Works and Coillte would have been found guilty of ecocide – not to mention the private interests which industrialised the seas or the politicians who allowed the conversion of natural riches into short-term profits.

I am not suggesting that these people and entities be sued in retrospect (if that were even possible). I am suggesting that these bodies now have a duty of reparation and restoration for the damage they have caused.

What I am calling for is a fundamental reappraisal of our relationship with nature. I am drawing on international initiatives such as the UN’s Decade of Ecosystem Restoration which will last for the 2020s, along with the ever more urgent need to de-carbonise our economy and to draw down carbon from the atmosphere.

To some people this may sound threatening, and I am talking about changing every aspect of how we do business and live our lives. But I also want to assuage fears that this will be a zero-sum game, i.e. that allowing nature to grow necessarily means a retreat of humanity and commerce. People may see calls for rewilding as equivalent to depopulation and abandonment, the loss of their culture and communities. I strongly feel that this is not the case. What I am looking for can be summarised in the following points:

But more than these administrative measures, we need to be able to reimagine our country. We need big ideas that can show people that dealing with the ecological emergency need not mean sacrificing our way of life. In fact, we can deal with these issues and make life fairer and better while we’re at it.

I hope I’m not asking too much. To live in an ecologically stable, more equal, healthier world that does not imperil the future of our children will discommode some I have no doubt. But I hope that most people will see it for what it is.

To help in this I want to promote six big ideas (not all of which are mine I should point out) for specific places in Ireland. I have tried to meet the people already working on them and to visit the places where I imagine they will unfold, and to figure out how to overcome the barriers to implementing them.

These ideas are fully in line with the advice by scientists for staying within planetary boundaries. Specifically they are fully compatible with our existing environmental legislation and the Paris Climate Agreement to keep the Earth’s temperature within 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

Studies have shown that restoring soil on farmland, bringing back large, native forests, protecting the oceans and rewetting peatlands can bring us nearly one third of the way to meeting this target. The biologist Edward O. Wilson has proposed setting aside half of the Earth for nature. This is possible within a stabilised human population, something which is now expected to happen by the end of this century (see www.half-earthproject.org). Wilson is thinking more about protecting the great diversity of life on Earth as well as the ecological processes which are essential for human welfare and the avoidance of mass extinction. But the science which brings these two goals together is rapidly advancing.

A paper published in 2019 added its voice to the call for a Global Deal for Nature, a companion agreement to sit alongside the Paris Climate deal.

The researchers are calling for 30% of the Earth to be formally protected by 2030 and for this to increase, through what they term ‘climate stabilisation areas’, to 50% by 2050. The risk here is that Ireland will turn up to this meeting (originally due to take place in Kunming, China at the end of 2020 but postponed to May 2021 due to the Coronavirus), say all the right things, sign up to whatever’s going, and then come home pretending nothing of interest happened.

I say this not because I’m particularly cynical but because this has been the Irish government’s strategy in previous such meetings. They may well feel it has served them well up to now. But I feel that already they’ve run out of road.

The ‘half Earth’ researchers say “this approach not only safeguards biodiversity but also is the cheapest and fastest alternative for addressing climate change”[vii]. They also caution that while headline goals are simple and easy to communicate, they can be fudged by authorities who find ways to protect areas with little added value, or just because the risk of conflict is low.

The scientists promote a ‘bottom up’ approach at the local level for deciding how much and where should be protected. Plus, it is not necessary to equate giving land to nature with ‘human-free’. Some human uses are compatible with preserving naturally functioning ecosystems. In Ireland, at least, restoration will need hands-on management for the foreseeable future (e.g. to eradicate invasive species or to control herbivores) so that nature conservation in itself could become a significant employer of local people.

We also need solutions for other areas so that farms and cities can be more nature-friendly. In reality what I am proposing is a menu of options that will lead people away from the most damaging practices and towards those alternatives with the greatest potential for meeting climate and nature goals.

The solutions I have in mind could be applied in many areas of our island but I thought it would be easier to imagine a future Wild Atlantic Rainforest, a Pearl Valley Farmland or a Shark Coast if I restricted it to particular areas.

The danger with all big ideas is that they may be seen as being imposed upon people particularly when they come from people (like me) who don’t live or work in these areas. Even in the area I do live in (Dublin) I still have to convince 1.5 million people that more nature in the city is a good idea.

Unlike in Britain, where there are relatively few landowners and people with deep pockets willing to advance ideas for ‘rewilding’, in Ireland we have many family-run farms and commonages with only poor environmental groups and no big donors. All we have is the power of our ideas and our willingness to win hearts and minds. So I am emphasising that these are ideas that could become reality. By default I think that these are good ideas and I would love to see them realised, but ultimately if this is to happen it must be for local people to decide.

In the next episode I will look at the Wild Atlantic Rainforest – could we really create a large expanse of oak forest across the west of Cork and Kerry? Imagine throwing on your backpack and walking all day in one direction under an unending canopy of leaves and branches. I hope you can tune in.

[i] The Invention of Nature: The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt. Wulf, A. 2015. John Murray.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] On Care for our Common Home, Laudato Si: The Encyclical of Pope Francis on the Environment with Commentary. 2013

[iv] Laudato Si: An Irish Response. Edited by Sean McDonagh. Veritas.

[v] Leopold A. 1949. A Sand County Almanac. Oxford University Press.

[vi] ‘Summit to Save the Earth by Philip Elmer-DeWitt. TIME. June 1st 1992.

[vii] Dinerstein et al. 2019. A Global Deal for Nature: Guiding principles, milestones, and targets. Science Advances.