It’s all happening at sea. This week the ESB announced that the coal-fired power plant at Moneypoint, on the west coast of Co. Clare, would be repurposed as a renewables hub to service floating off-shore wind turbines and the production of hydrogen fuel. In an interview in the Irish Times one of the ESB directors, Jim Dollard, was upbeat in his assertion that the utility is ready for the energy transition. When asked if the goal of 30 gigawatts (GW) of offshore renewable generation was realistic (the 2019 Climate Action Plan set a target of 3.5GW by 2030), he answered that “I think the energy is out there… It’s a matter of how and when, I don’t think it’s whether”.

This is good news. Ireland has a lot of catching up to do and our country is still primarily powered by dirty fossil fuels. Building wind farms on land can be problematic as they are generally unpopular and can come with serious ecological impacts (the IWT has objected to a number of them over the years). In theory, the potential for offshore wind could take pressure off the land although there is no evidence that this is actually happening (both Coillte and Bord an Móna have big plans for wind development on public land across Ireland).

As well as the wind farm proposed off the coast of Clare, there is a 140-turbine array planned for the Irish Sea off the coast of Co. Wicklow (see www.codlingwindpark.ie) while Simply Blue Energy have joined forces with fossil fuel giant Shell to develop a 1GW wind farm off the south coast of Co. Cork.

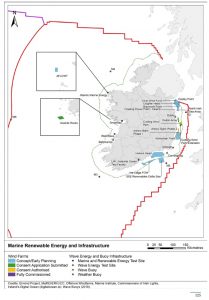

From the draft Marine Planning Framework

The only snag to all of this is that there is currently no legal mechanism to approve large projects like these in the marine zone. Enter the Marine Planning and Development Management Bill which is set to modernise our out-dated planning laws and which is due to be enacted shortly.

Ireland is also subject to the EU’s Maritime Spatial Planning Directive and was due to submit a plan to the European Commission by the end of March. This deadline has come and gone but this week the civil servants answered questions to the Oireachtas committee on Housing, Local Government and Heritage in advance of the approval of the draft plan, officially titled the National Marine Planning Framework. It’s an arduous 341 pages long. The directive says that member states must base their plans on an ‘ecosystem-based approach’. This is not optional and so the protection, restoration and wise use of marine ecosystems must be central to this process.

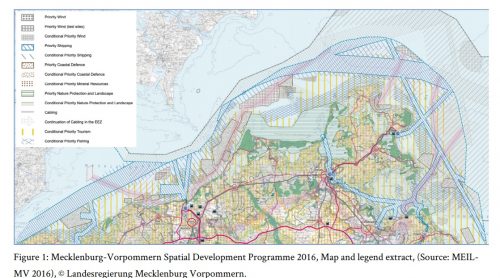

You’d expect a marine spatial plan to come with maps, particularly maps showing what activities are to be allowed where. Anyone familiar with planning on land will know about the colour-coded zoning maps that come with County Development Plans. They’re the bits that everyone is interested in as they tell you where new housing or infrastructure is going go and where is to be zoned for other uses, such as open space or nature conservation. Indeed, a document entitled ‘Best Practice in Maritime Spatial Planning’ published by the Greens in the European Parliament, and which comes with a forward by Waterford MEP Grace O’Sullivan, comes with examples of best practice and exactly these types of maps (see extract below).

Best practice – how zoning in the marine environment is supposed to be done

Ireland’s draft maritime spatial plan does have maps, lots of them, but nothing like these zoning maps which are ‘best practice’. And there is one especially glaring omission: Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

At the Oireachtas hearing this week, Sinn Féin’s Eoin Ó Broin highlighted this omission to the department officials, suggesting it was a back-to-front way of going about business. “We don’t have those designations, we don’t have them mapped out, we don’t even have sensitivity mapping of where they might be” he told the hearing.

Supporters of the IWT will know that we have been crying out for MPAs for a long time and even at senior government levels it is acknowledged that we are way – way – behind meeting our international obligations.

This included protecting 10% of our seas by 2020 (currently the figure stands at a shade over 2%) while the programme for government commits to 30% by 2030. Even this is likely to be too low and a recently-published report on MPAs recognised that the scientific consensus is moving towards 50%. Yet, we’re nowhere near designating any MPAs. The report highlights that the term doesn’t exist in Irish law and so new legislation will be required. There is currently a consultation open on the process and will end on July 30th. It will then be up to the Oireachtas to publish legislation, which than has to be scrutinised and approved, and only then can we start to look at where the MPAs will actually go.

So, to summarise: we have a marine renewable energy industry in the starting blocks and announcing plans left, right and centre. We have a planning law needed to fire the starting gun which has yet to be passed and we have a legally-binding spatial plan that is overdue but set to be shortly approved in the complete absence of a single MPA.

MPAs are still a long way off and so there is no escaping the fact that if this goes the way the government is planning, then the industry will have taken their pick of development sites and the MPAs will just have to squeeze into whatever is left over.

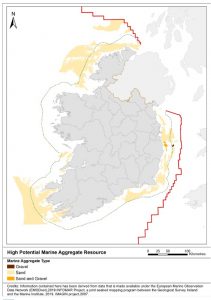

And it’s not just wind turbines we need to be concerned about, there is also a nascent industry in marine mining, including sand and gravel extraction, that will not be shy about muscling in when the time is right. The draft spatial plan is fully supportive of marine mining and aggregate extraction and, unlike the MPAs, there is a map for this.

From the draft Marine Planning Framework: the state seems keen to highlight these areas but not MPAs

So, despite all the plans, the weighty documents, EU directives and pronouncements from ministers about the biodiversity emergency – this whole process stinks of business as usual; nature, as is so often the case, can get stuffed.

Is there way out? The Oireachtas committee, chaired by Steven Matthews of the Green Party considered all of these issues in recent months. It recommended that the Marine Planning and Development Management Bill should include for the designation of MPAs and it’s not too late for this. Their report also suggested that, if this option is not pursued, that ‘sensitivity mapping’ is done to indicate where the MPAs are likely to go. This is also a recommendation in the MPA report. It is likely that we have enough information already to do this despite some shortcomings in the data. I would urge Minister Eamon Ryan, who is championing the energy transition, to commission this work with the same level of urgency that he is (rightly) pursuing the roll out renewable energy.