17th of September 2022

Will Ireland’s new Forest Strategy prove to be the acorn that went on to be a mighty oak? Or will it be a seed in the wind, destined to land on stony ground? It’s hard to get excited about new strategies, given our long history of producing plans that are subsequently ignored. But, on the other hand, we can’t undertake long-term reform without a solid strategy. In this case, at least, a lot of time and effort has gone into developing this document as part of Minister Pippa Hackett’s ‘Project Woodland’ (the Irish Wildlife Trust has been a part of this and have had a seat on the sub-group which developed the Strategy). This week, in advance of its publication, a ‘Shared National Vision’ has been produced along with a summary of the many and various public consultations which have been undertaken in the last year.

This week has also seen the publication of Eoghan Daltun’s wonderful book ‘An Irish Atlantic Rainforest’. Eoghan’s twitter feed has captivated thousands with the unfolding of his sylvan idyl on Cork’s Beara peninsula. His book is a love letter to the forest that captures its beauty and drama but there is a simultaneous plea for us to unleash nature’s self-restorative powers at a wider level. He recently exhorted that “rewilding – on a mass scale – is the primary solution to the collapse of biodiversity in Ireland”. Controlling grazing, as well as other invasive species, is the key to kick starting the restoration of Ireland’s forest ecosystem. So, will our new Forest Strategy tap into the power of rewilding for this purpose? We’ll have to wait until the final version is published but I have a number of reasons to be concerned.

The work to develop the Strategy over the past 18 months or so has been a happily collegial affair with our small group of ecologists, foresters and staff from the Department of Agriculture having many open and respectful discussions. I have got to know them and have learned from their perspectives. We visited native forests, production forests of different types and a sawmill where wood products are made. We all agree that Ireland needs a lot more forests and we should do this quickly. We all agree that timber and wood products can and should play a role in a decarbonised future. There is acceptance across the board that our native forests are in a pitiful state and need urgent and dedicated intervention. But my worry is that this level of accord masks deeper differences in what forests are for.

My first red flag went up when I noticed that the draft Strategy failed to fully endorse the EU’s own Forest Strategy. I wrote about this important document last year as it aims to bring an end to the industrialised monoculture/clear-fell model of timber production. When I asked Minister for the Environment and Green Party leader Eamon Ryan on twitter last year if the Government backed the EU Forest Strategy, he replied “yes”. So why is the Department of Agriculture reluctant to state this clearly?

My first red flag went up when I noticed that the draft Strategy failed to fully endorse the EU’s own Forest Strategy. I wrote about this important document last year as it aims to bring an end to the industrialised monoculture/clear-fell model of timber production. When I asked Minister for the Environment and Green Party leader Eamon Ryan on twitter last year if the Government backed the EU Forest Strategy, he replied “yes”. So why is the Department of Agriculture reluctant to state this clearly?

My next red flag went up when the draft refused to acknowledge the need for restoration of forest ecosystems. In my view, this is the most important thing we need to do. It does not mean returning to 80% native forest cover but it does mean restoring the scale and health of forests so that they provide habitat for all its species, is resilient to environmental changes and is capable of regenerating itself over time. This is, after all, the UN decade of ecosystem restoration while the European Commission is pressing ahead with its own Nature Restoration Law. So why is there a reluctance to use these words and engage with these ideas?

The final red flag is in relation to the use of biomass as a substitute for fossil fuels, which the Strategy is set to ‘promote and support’. This is a terrible mistake. While the burning of wood pellets can be a useful by-product from sawmill leftovers, it should not be supported with public money as the risk of perverse outcomes is too great. See here for more background on this, but essentially biomass is not a sustainable fuel at scale. Burning wood, just like burning fossil fuels and peat, needs to stop.

And what of the scope for rewilding? Using natural forest restoration wherever possible is internationally accepted as the cheapest, quickest and most effective way of creating new forests – so will this be front and centre in our approach? So far, it doesn’t look like it.

Forests are complex natural ecosystems that can deliver multiple benefits, including commercial products. But my feeling is that the sector has not let go of its production-centred, commercial mindset. It sees climate change, or more accurately, climate targets, as an opportunity for expansion without any fundamental change to its business model (more monocultures and clear-felling). It has one eager eye on future carbon markets that would funnel significant revenues into the sector.

But it continues to overlook two critical points. The first is that monocultures are inherently vulnerable to present and future climate shocks (maybe the industry’s models have discounted yields in the second half of this century so that this is not of great concern to them once establishment subsidies and carbon credits have been drawn down). The second though is a more fatal blow to their plans: public opinion.

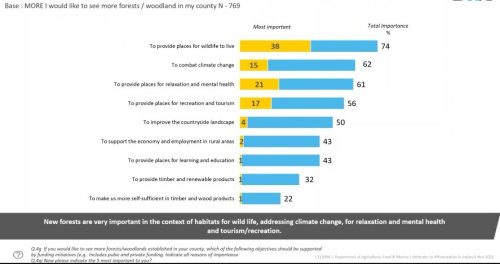

There is simply no public support for a continuation of business-as-usual in forestry. The result of the Department’s extensive consultations (including public surveys, a citizens’ ‘deliberative dialogue’ and a dedicated study by Irish Rural Link members which included the ‘Save Leitrim’ group) has shown clearly that people want more diverse forests, more native forests and, primarily, forests that will deliver for climate and biodiversity. There is no acceptance of more blankets of non-native conifers that shut out people and nature. The social contract that allowed for the ploughing of our bogs and hillsides and the

replacement of small farms with ‘dead zones’ is itself dead.

Extract from public forest survey

An alternative is what Eoghan Daltun has done on his patch of land jutting into the Atlantic Ocean: to work with nature. To give it time and space to heal and to take only what it is capable of giving. So far, I don’t see this fundamental shift in thinking about our forests within the industry or state bodies. He should send them all a copy of his book.