Glen of the scarlet-berried rowan

Fruit praised by every flock of birds,

For the badgers a sleepy seclusion

Quiet in their burrows with their young

14th Century Irish poem

c. Naomi McBride

It is no more than a twig the size of a chopstick standing upright in the ground. Only its single, serrated green leaf gives it away, not only as being alive, but as to its identity. It is a rowan tree.

Little about its frail finger of a ‘trunk’ gives any hint that this plant could, one day, become a tree worthy of the name. Nothing epic, mind you: the rowan does not grow to be ancient or mighty like the oak or the beech, but it can stretch to 15m in height – decent enough.

In early summer it bears great plumes of creamy flowers, its faint haze drawing flies and bees to slake their thirst for nectar. In autumn these turn lipstick scarlet, weighing down the slender pedicles and providing a great feast for blackbirds and thrushes.

At the same time, its leaves put on a show of colour not out of place in a Gustav Klimt painting. Even in winter its taught bark is colonised with mosses and lichens that lend light and texture even on the darkest days.

These are known as ‘epiphytes’ – plants which grow on other plants, and indeed the rowan is known to be an epiphyte itself – doing just fine on the crest of an upturned mass of tree roots or finding a nook in a sheltered cranny of a small cliff or ancient oak.

The rowan is not especially flashy like the cherry, and never defines a place like the oak or willows do (you’ll never visit a ‘rowan forest’). It does seem to fit in though, nestling perfectly in its chosen spot, accommodating itself nicely to the earth and vegetation around it. Who knows why it was revered as fid na ndruad, ‘the druid’s tree’, in ancient times.

Nor why it seems to have attracted a disproportionate volume of folklore, such as how it could stop the dead from rising (easily proven you might imagine), or that eating a rowan berry from the tree planted by the fairies on the slopes of Ben Bulben in Sligo would guarantee you’d live to at least 100.

The unassuming rowan tree has made itself at home in the human imagination just as it does in our damp, crumbly earth. The rowan that I’m looking at, sadly, is unlikely to have such an illustrious future.

Nothing too flashy, but the Rowan tree is a hugely important tree for wildlife.

It’s April and I’m in Uragh Wood, a brushstroke of ancient oak woodland along a hillside on the Beara Peninsula in County Cork. It is a fragment of the rain-drenched Atlantic Rainforest which once clothed the western half of Ireland and it’s hard not to be impressed by the size of the trees and the lush vegetation which hangs from their branches – epiphytes, as we now know to call them, great wads of flappy green lichens called ‘lungwort’ (for the pattern on its upper surface) and ferns, including the cellophane-like filmy ferns, tiny in comparison with some of their cousins, and right at home in these rain-drenched valleys.

At least, so long as you keep your eyes pointing upwards, the forest might look something like it did two millennia ago, when the great woodland still stretched out along the fingers of west Cork and south Kerry.

But the forest floor is something altogether different: it’s completely bare. Apart from a mat of last year’s dead leaves and the moss-covered rocks, there are no plants. Perhaps this is something only noticeable to the trained eye, but this forest is entirely missing its ground flora and not only that, there are no young trees.

Apart from my valiant rowan pushing its head up through the leaf litter, this forest has had most of the life sucked out of it. In fact, it’s all being eaten by a three-pronged herbivorous army of non-native Sika deer, goats and sheep. I admire the little rowan, how it must make do with its circumstances, so full of potential, so eager to be part of the forest community – if only it were given a chance it would have so much to give.

Severe overgrazing in Killarney National Park – notice the lack of shrubs

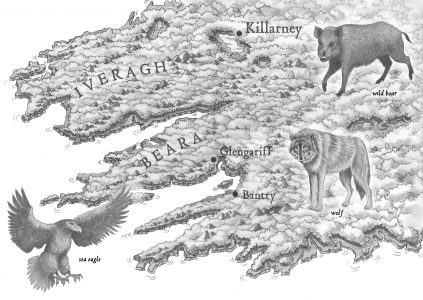

Were it not for the army of hungry munchers it would help rejuvenate the forest. And I don’t mean just Uragh Wood – that’s tiny – I mean the forest: the Wild Atlantic Rainforest, which could – if we wanted it to – stretch from the outskirts of Macroom, right out into the Atlantic Ocean via the fan of peninsulas from Dingle in the north to Mizen Head in the south.

How easy – or difficult – would it be to realise this vision? Clearly, ancient forests don’t just spring up in 10 or 20 years but it’s surprising how trees, just like our doughty rowan, are already waiting in the wings for their chance to reach to the skies.

Many of these trees, like the rowan, birch, willow and hazel can literally spring out of the ground in an incredibly short space of time. Allowing the trees to return would transform the landscape, from one which is largely open and barren today, to one which is lush and teeming with life.

An enormous oceanic rainforest, which joins up existing fragments of native woodland like the one in Uragh with others in Killarney National Park and elsewhere would be a wondrous place. It would help restore threatened habitats, like the few bits of old oak woodland which remain, and species, such as the freshwater pearl mussel (because native forests are so good at cleaning water).

It would suck up an enormous amount of carbon and I have no doubt would be a hit with locals and visitors alike as an amenity resource. I have always dreamed of a place in Ireland where you could sling on your backpack in the morning and walk for the whole day in one direction under a canopy of leaves, something I have so far only been able to do in other countries.

The Conor Pass, Co. Kerry. Many consider our bare and barren hills to be scenic and ‘unspoilt’.

The Wild Atlantic Rainforest would not function over the long term unless there was a large predator to control the numbers of deer. I have no illusions that this would be met with outright hostility in certain quarters. People will have an instinctive reaction to wolves, but what about the much shyer lynx?

Or what about bringing back wild boar – another essential component of our woodlands but a big animal which would make its presence felt?

There are those who find the prospect of reintroducing long-lost large animals thrilling (and – for the record – I’m one of them!). But then I don’t live in the south-west and I don’t depend on the land for my livelihood. I have no doubt that a discussion about even having more trees in the landscape will rouse deep emotions, but my gut feeling is that most people really have never thought about it at all.

The hillscape of the west of Ireland has been like a wallpaper to people’s lives and has left an impression of how the countryside should look. It can be seen in paintings hanging in the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin as well as postcards all along the ‘Wild Atlantic Way’.

Yet these impressions are flawed in one respect – simply because so many changes have already occurred to this landscape. Look at the proliferation of plantation forestry which has marred the landscape but which has been widely tolerated because of the impression that it brought jobs and economic activity to areas with few job opportunities.

On this basis, would the return of large, forested areas be similarly accepted? They would bring economic opportunity but, I would argue, one that is much more widely spread than single-focus land uses like monoculture plantations. Could people overcome their initial apprehensiveness, particularly about large animals roaming the hills, if they could see the direct benefit in terms of people staying in rural areas and strengthening communities?

I am aware that I am walking on culturally ‘thin ice’. There is a long history of people, typically middle-aged, men from urban backgrounds (i.e. just like me) imposing their vision on a landscape where the local people do not feel like they are involved.

This has traditionally been more about power– who gets to wield it and why – and resource grabbing, particularly when the resources are public monies in the form of subsidies. The current rash of planting taxpayer-fuelled conifer plantations in places like County Leitrim is a demonstration of this.

I can’t help my gender, my age or my background. Perhaps to some, these are grounds enough to discount my views. What I can do is try to bring in the voices of people who may be able to shine a light on my blind spots. My wish is not for people to disappear off the land to be replaced by wolves and bears – rather, my wish is for people to regain control over their land, something which has been robbed from them by a rain of subsidies, bureaucracy and lobbyists who claim to have their best interests at heart. My hope is that were people to be handed this power, they would choose to live in a landscape that is rich in thriving nature.

Could people come to accept large animals living in the woods? Image source: Christels via Pixabay.

My point of entry to the Wild Atlantic Rainforest starts with Eoghan Daltun, a man who has taken what many urbanites would consider to be a dream escape from Dublin’s hard edges and smoggy air to the bracing winds and soft contours of west Cork.

When I visit him in his home outside the village of Eyeries, near the western end of the Beara Peninsula, it is ten years since he left the city to start a new life as a west of Ireland hill farmer. Only his accent now betrays his Inchicore roots:

“I’ll always be a blow-in” he says resignedly but without a hint of regret. Eoghan bought a farm that came with a share in a commonage – a swathe of land on the hill above his house and where a blue stain distinguishes his sheep from those of the co-owners. His home commands enviable views over the ocean and even, on a good day, the Skellig Islands off Kerry’s Iveragh peninsula.

But Eoghan didn’t come to this place for the view, at least not in the literal sense. He had a view all right, but only in his mind’s eye, and it is one that must have been hard to visualise when he first arrived. “When I got here the land was in poor shape. Yes, there were trees but there were sheep …and goats, they had eaten pretty much everything… no plants on the ground while many of the trees had been killed because the bark had been stripped from them”.

Eoghan feels there should be a tenth circle of hell just for goats. “Goats eat everything, I mean anything, they even climb trees!” Feral goats are descended from animals brought to Ireland three to four thousand years ago from the Middle East where they evolved to climb mountains and eke out an existence in arid conditions. They’re the only animals I have seen in Ireland which can munch their way through gorse, a plant so spiny it would, to us, be like getting your lips around a porcupine.

Eoghan applied for a government grant under the Native Woodland Scheme which provided funding to erect a deer-proof fence around his farm. He then arranged to have the goats and sheep escorted off the property.

He also spent a lot of time removing the invasive rhododendron not only from his own property, but from surrounding areas where new seeds might find their way onto his land. Normally under these schemes the next step is to start planting trees.

A forester would come in and choose species considered suitable and they would be placed in the ground at appropriate spacings, perhaps within plastic tubes to stop hares eating the saplings. People love planting trees almost as much as they love tearing them down. It is seen as a panacea to all environmental ills. It gives people something to do and no doubt lends an air of satisfaction to the planter.

When the saplings die, as they frequently do when plonked in ground for which they were unprepared, people are quick to conclude that ‘trees won’t grow’ in that spot. Thorny trees and bushes are dismissed as useless ‘scrub’ in the planter’s impatience to see an ancient oak forest unfold in 10 to 15 years.

Where pockets survive, the Atlantic rain forest bursts with life

The eagerness of the planter overlooks the fact that trees have been planting themselves quite successfully for millions of years. In fact it was Oliver Rackham, an authority on trees and woodland if ever there was one, who quipped: “Tree planting is not synonymous with conservation; it is an admission that conservation has failed”.

Eoghan has read Oliver Rackham’s books, and a lot more besides judging from the expanse of bookshelves in his living room – something akin to a small library that is rare to see in homes today.

So after the fence went up and the farm animals were gone he did something that is anathema to many environmentalists: he waited.

It would not be fair to say that he did nothing, because close observation is not passive. So he observed – patiently, intensely and his waiting and observing were surprisingly quick to pay off.

What had been a smooth lawn of unidentifiable shoots soon became a lush carpet of wood anemones, bluebells, wood sorrel, ferns and bramble. Greenery closed in on the little stream running through the land, the water now sparkling in its translucence.

The holly, which had much of its bark stripped by the goats, was springing forth new shoots. When I visit in early 2019 it is hard to make out the pattern of the farm that was there before it; in only 10 years the transformation has been dramatic. As we make our way through the undergrowth Eoghan points out details for my attention – “that birch just appeared in the last three years, look at it now!” The tall oak and ash which had been growing before he arrived were mother trees, now casting their offspring on ground where they at least have a chance of survival.

This is not gardening – it’s the opposite. It’s relinquishing control over the surroundings – something humans find challenging to say the least.

Eoghan is keen to show that the land is pregnant with life, if only we had the courage to allow it flourish. He is conscious of local sensitivities (his neighbours no doubt think it eccentric to own land but not farm it) but he also brings school tours to see what a real Irish forest looks like.

The children collect bugs and creepy-crawlies, try to identify them and then release them back to the forest.

“People gain a different appreciation of the landscape and the value of the woodland,” he tells me.

Across the road there is a small field which is outside the deer fence and still gets some grazing by sheep for a few weeks of the year. But this is not enough to overwhelm the vegetation and already there are signs of the forest re-emerging – a flush of bluebells has appeared where they had not been seen before.

Bluebells are synonymous with our native woodlands and have relatively heavy seeds which do not disperse easily. For these reasons they are considered an indicator of old or even ancient woods, and where they emerge in the absence of surrounding trees it is likely to be a sign that here once stood a forest.

The haze of indigo is like the first dip of a painter’s brush in water – it hints at possibility; the masterpiece that awaits. And already the other brushstrokes are apparent: the anemones, the pignut, the hawthorn and the rowan trees.

Later in the day we walk to the higher ground, the patch of commonage which Eoghan shares with a small number of other farmers. It looks out over a narrow inlet and the great expanse of Atlantic Ocean beyond.

On dry land though, the great expanse is of brown grass and bare hillsides. Eoghan explains to me how all of these hills could be lush with Atlantic rainforest just like his small corner. Farming sheep here is not profitable and only continues because of the subsidies provided by the government.

Most sheep farmers do not rely on this for their income, instead having jobs elsewhere, but keeping sheep for other reasons – the few extra quid or perhaps keeping up a tradition in the family.

What if the subsidies were to change? What if there was a financial incentive for commonage owners to farm less?

For Eoghan there is little doubt that if the price was right, the sheep could be removed from the hills. This is sometimes seen as land abandonment but in fact there would still be a need for people.

The invasive rhododendron lurks in these peatlands and payments could be linked to keeping the land rhododendron-free. Sika deer, another invasive species, is also found on the Beara Peninsula and, for the foreseeable future, their numbers need to be controlled by people. There is employment in path maintenance for walkers or guides for visitors. So abandonment is not the desired outcome. In fact, it is likely that more, and more diverse, employment opportunity linked to the land would arise.

Rhododendron (seen here in the foreground) is an invasive species which will strangle the Atlantic rain forest if not controlled.

The next day Eoghan and I meet with Clare Heardman, the local ranger for the National Parks and Wildlife Service and is it Clare who introduces me to Uragh Wood Nature Reserve.

It’s a cold day for April and a charcoal sky threatens rain. We stand on a hillock overlooking Gleninchaquin Lake and the ancient forest beyond.

Clare points out a relatively new area of woodland next to the Uragh Reserve which was established by a local farmer under the Native Woodland Scheme and although it lacks the very old oak canopy it is impressive how well the birch, willow and rowan have made themselves at home. There’s another patch of land previously planted with conifers by state-forestry company Coillte, which was clear-felled (i.e. all the trees were taken down in one go) and then native trees were allowed to colonise all by themselves.

In fact, I’m taken aback at how many trees are already growing in this landscape. Compared to some parts of the country, such as Connemara, it is positively lush. We spot a family of goats wandering through the valley floor while higher up the hilltops are as bare as anywhere else.

The Uragh Wood Nature Reserve itself had a deer fence but a part of it fell down and was not repaired – the lack of funding for simple measures like fence repair has set conservation of the reserve back a decade – but still, Clare believes the fence is due to be fixed and once the grazing animals are out the regeneration will be quick to get going again.

Clare later brings me on a drive across the mountain pass which leads from Kenmare Bay on the northern shore of the Beara Peninsula, towards Bantry Bay on its southern shore. The weather now is closing in but despite the rain the changes to the landscape are apparent.

We first past through a band of small farms along narrow roads with boundaries so leafy the trees almost meet in the middle. On open ground the signs of woodland emergence are everywhere – it is astonishing to see just how extensive the growth of scrub has been.

This really is land abandonment, because outward migration and low economic viability have led people to turn their backs on the land. The new native trees are a sign of healing but were rhododendron to take hold it would strangle any ecological recovery.

As we descend on the southern slopes, we stop to look at a new project funded by the Native Woodland Scheme near an important roost for the rare lesser horseshoe bat. The foresters here have opted not to erect an expensive and maintenance-intensive deer-proof fence, but rather there is an array of hundreds of plastic tubes, each one containing a native tree sapling.

Each tube is secured by a plastic cable-tie to a wooden stake. The tubes protect the saplings from being eaten by deer, hare or rabbits. But at the same time the tubes are not ideal.

The saplings frequently die inside them, sometimes baked by the microclimate when the sun shines (something akin to a greenhouse). This can be an ideal environment for pests or disease. Their stems do not respond to the natural climate and so can be weak when the tubes are eventually removed, leaving them more prone to blowing over.

All that plastic and plantation grown timber is resource-intensive which requires someone to return to the site many years later to retrieve thousands of items of unrecyclable materials. On the other hand, if the grazing on the land was controlled – e.g. by removing domestic animals or managing deer numbers, the land would quickly cover itself in thorny brambles or gorse.

These are natural herbivore excluders and protected nursery zones for sapling trees which eventually overshadow the brambles to move on to the next stage of woodland creation.

As the wind blows the rain sideways our final stop is the main road which overlooks the Glengarriff Nature reserve. This patch of forest is a rival to Killarney for its ancient oaks and rushing waters lined with stooped boughs of oak and alder. Clare tells me how plans to buy land adjacent to the reserve, and so create a much larger Glengarriff National Park, were stymied by the economic recession over a decade ago.

Some of the surrounding land is already owned by state companies, such as Coillte, and in the last decade or so clear-felled conifers have been replaced with locally-sourced oak saplings. Buying land, particularly commonage land, by the state to expand nature reserves and national parks is another option for restoring the Wild Atlantic Rainforest and one which should be complementary to subsidy schemes for private landowners.

The lack of resourcing for the National Parks and Wildlife Service however has been so debilitating that even when they have been given land, there is no money for management plans, public engagement or actually implementing any conservation measures.

When the state bought nearly 2,000 hectares of land to expand the Wicklow Mountains National Park at the end of 2016, the announcement was accompanied by assurances to local sheep farmers that their grazing regimes could continue. In other words, the expansion of the national park would in no way affect how the land was going to be managed.

The wind and rain blast in our ears as we look down on the small cushion of treetops in the Glengarriff Reserve and we exchange forlorn glances at the opportunities missed which would have seen expansion of the forest well under way by now. From this point, with the right vision in place, it’s not hard to see the treetops spreading out from here to Uragh Wood and even reaching Eoghan’s rainforest on the edge of the peninsula much further west from here.

White-tailed eagles are now breeding in Ireland. Image source: Mike Brown

Retreating from the squalls, Clare and I talk about these issues over warm soup and toasted sandwiches. As we come to, we discuss local attitudes and whether the community is ready for a great expanse of forest or the reintroduction of large animals.

White-tailed eagles were released in Killarney National Park over 10 years ago, between 2007 and 2011 as part of a joint project between the National Parks and Wildlife Service and the Golden Eagle Trust.

Clare recounts how there was initially loud opposition from some quarters and a fair dollop of fear mongering. The eagles are far bigger than any other bird in this part of the world (although similar to the golden eagles released in Donegal a few years earlier) and are top predators.

Prior to the reintroduction of the two eagle species Ireland had been without a top predator (other than humans) since the early 1900s. Clare has been working to help build support among the local community and allay the fears held by some.

“I saw the attitudes change. As local people started to see eagles around Beara they were excited by the presence of these magnificent animals. Any fears quickly turned to understanding and respect once landowners saw for themselves that the eagles didn’t pose any threat to their livestock”.

Clare’s role in the introduction was vital as the birds soon spread out from Killarney and started nesting in the surrounding valleys and coastal areas where she works. One pair established a nest on an island in Glengarriff Harbour and is frequently seen by day trippers visiting nearby Garinish Island.

Another pair nested on private land and Clare made contact with the farmer to let him know.

Wild boar. It’s not only trees that are needed to make a forest – the animals are essential. Image source: Mikewildadventure via Pixabay.

“I gave him an old telescope and he set it up in his front room where he could keep an eye on the nest. He was originally hesitant as people had been saying that the eagles would prey on the farmers’ lambs. But after a while he was among the eagles’ biggest fans – he was so proud that they had chosen to nest in his valley!”

Clare’s knowledge and personal contact with the local farmers were key elements in local acceptance of the eagles. The farmer in question went on to boast about ‘his’ eagles to his neighbours and it is these conversations that changed perceptions. The return of the eagles brought no direct benefit to anyone in terms of farm payments or subsidy schemes.

Nobody benefits financially, and the farmer to whom Clare lent her telescope didn’t get a cent for watching over the nest, keeping Clare informed of the development of the chicks or spreading the word among his neighbours that he was the proud custodian of such impressive birds. He did it simply for the love of it and, presumably, the joy he got from his connection with wild nature on his doorstep.

The next morning I take a walk to ‘Lady Bantry’s Lookout’ in the Glengarriff Nature Reserve. It had rained non-stop since the previous afternoon and the river through the forest was swollen and turbid.

Unlike Uragh Wood, or the Killarney National Park not far from here, there are no sheep to be seen and deer have not eaten the forest floor to the soil. So here not only can you see the lofty branches and crenulated forks of ancient trees, but the air is alive with birdsong and the ground is awash with primroses, brambles, anemones and wild garlic.

The short trail is named after the wife of the Earl of Bantry and who, confined to a wheelchair, was lifted to the top of the hill for picnics in the 1800s. The view from the summit – if you put your back to the conifer plantation – is a rare one in Ireland.

Glengarriff Wood Nature Reserve, Co. Cork

Before you lies an expanse of treetop, curving with the rolling hills and seemingly stretching to the horizon. I imagine for a moment sitting here on a summer’s evening and the cloak of green fanning out in every direction – reaching the tip of the Beara peninsula, connecting with the Killarney National Park to the north and extending inland to the low hills of the Lee valley.

—

It’s May and I’m heading back to the south-west to visit a new project which is hoping to improve conditions for hill farmers and the environment.

I arrive in Killarney in time to take an evening wander out to Ross Island within the Killarney National Park. The evenings are stretching out now, and I arrive at Ross Castle to a near empty car park and the sense that I’m going to have the woods all to myself.

I’m not far wrong and I delve under the canopy just as the setting sun washes its waning light through the trunks of oaks and beeches. I have a quiet moment as I disturb a group of red deer hinds, but I don’t disturb them enough for them to bolt. They eye me carefully before relaxing and lowering their heads.

The forest here is not only unusual but unique. There are yew trees, familiar to most as graveyard trees, but in their natural setting their branches extend like fingers bristled with their evergreen needles.

They grow here in shady settings, their burgundy wood is known for its incredible durability while the trees can be as ancient as the forest itself. While many have been planted in churchyards, the association is likely much older than that as it is believed that in some cases the trees pre-date the churches.

In the Ogham alphabet the letter I is referred to as sinem fedo (oldest tree) and caínem sen (fairest of the ancients)[i]. Here also is the mystic strawberry tree, confined to a handful of locations around Ireland, absent altogether from Britain, and a tree believed by botanist David Webb to be practically immortal due to its ability to regenerate itself from a fire-proof, underground ‘lignotuber’[ii].

He believed the strawberry trees in Killarney sprang from seeds over a thousand years ago. Walking along the path to the tip of the peninsula it is possible not only to imagine but to see what the Wild Atlantic Rainforest looks like and smells like and feels like.

With a little imagination it is possible to believe that wild creatures still roam its shadowy places and that a day’s hike would only bring you deeper into its heart. But this is not why I came to Killarney.

One of the more positive developments in addressing farming and the environment in recent years has been the appearance of European Innovation Partnerships (EIPs).

The idea is taken from the successful model of farming with nature pioneered in the Burren, County Clare at the turn of the century and is based on farmers using their knowledge of the land with scientists and government agencies to produce well-defined results. One of these is based in the MacGillycuddy Reeks along the Iveragh Peninsula, that’s the peninsula just to the north of Beara, and is best known for the Ring of Kerry and Ireland’s tallest peak – Carrauntoohill.

It’s relatively easy for me to find people who think restoring the rainforest is a good idea and I think that ideas for actually achieving this are pretty well-established. However, I am keen to speak to people with a background in farming in the area.

The timing of my visit is ominous, even if I didn’t plan it that way. The week before, the United Nations Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES – a scientific forum assessing biodiversity along the lines of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) released a devastating report on the state of the planet’s ecosystems.

It warned that humanity’s very survival is being threatened by the unsustainable exploitation of forests, wetlands, oceans and freshwater bodies. Up to a million species are at risk of extinction by 2050 unless urgent action is taken. As if to underline that these global reports are hitting home at the local level, days later an Irish species took one more stride towards extinction in Ireland.

The ring ouzel looks very like a common garden blackbird except for its distinctive white bib. Once common across upland and hilly areas of the country it had been reduced to two populations – one in Donegal and the other in the Macgillycuddy Reeks of Kerry. Dr Alan Mee of the Golden Eagle Trust tweeted “On the same day as IPBES report hit the headlines, [I] covered most of [the] main ring ouzel sites in Reeks Kerry with… no birds located. Sad but likely witnessing local extinction of the species, once found in 28 Irish counties”.

Against this backdrop I head to Beaufort and the office of the Macgillycuddy Reeks EIP and on a gloriously sunny spring morning I sit in the garden with the project manager Trish Deane and project ecologist Mary Toumey.

We’re literally sitting at the foot of the mountains which look stunning with crowns of little fluffy white clouds. Mary is from Dublin and was once a biodiversity officer for a Dublin local authority while Trish is from a farming family on Slieve Mish on the Dingle Peninsula.

She’s a proud Kerrywoman and has a no-nonsense air about her. Mary and Trish’s job for the next three years aims to “improve the sustainability and economic viability of farming the Macgillycuddy Reeks” while at the same time enhancing the biodiversity of the mountains.

The entire area falls within a Special Area of Conservation (SAC), identified as among our most important conservation sites since the late 1990s and the release of EU funds aims to develop farming which is compatible with the aims of the SAC.

I ask Trish about her upbringing and the changes that have occurred in recent decades. “When we grew up we had a few cattle on the hills and some sheep on lower ground but the cattle disappeared and only the sheep stayed on. But farming is dying out, there are very few new farmers in this area, most are in their 50s and 60s and don’t have family members to take over.”

She is frustrated at the policies which have allowed this dramatic cultural shift to happen. She talks about a few landowners who ‘farm the subsidies’ on offer despite not living in the area or even farming the land.

She has worked in the field of rural development for some years and has helped put a human face on government programmes. She tells me how she helped one elderly farmer apply for a state medical card – “he had no idea how much money was going out and was shocked when I told him that it was more than what he was getting in”.

Like nearly all farming in Ireland, sheep rearing is entirely dependent upon state subsidies. I ask Trish and Mary about the condition of the land and they would agree that in most cases the vegetation is over-grazed.

The rules under which farmers are eligible for the basic subsidy payment are contingent upon the land being in ‘grazable condition’. This has led to burning of land, razing of scrub and destruction of important habitat for which the SAC is designated.

Although the project had only been under way since the second half of 2018, Trish and Mary have already walked the land and have met with every farmer. One of the main outcomes of the project is what Trish succinctly refers to as “the learnings”.

She tells me how when she asked the farmers why their land was in an SAC – i.e. what were the habitats or species which made it special – only one knew. “Nobody ever told them,” she explains.

The farmers (somewhat belatedly) are now gaining from Trish and Mary’s ecological expertise, while at the same time, imparting their own intimate knowledge of the mountains to each other and the administrators.

I’m slightly taken aback at just how underdeveloped and neglected communication has been even at this basic level. It goes a long way in explaining why both upland farmers and the ring ouzel are facing a similar fate.

The Macgillycuddy Reeks are among the most popular walking areas in Ireland and the increasing numbers of visitors have had little benefit for local landowners. Private walking tours are not obliged to contribute financially and the farmers see the use of their land as a “free-for-all”.

A part of the project will involve the farmers being paid for path maintenance, for keeping walkers on the main tracks and for reducing the impacts of trampling and erosion.

They will also be paid for tackling rhododendron clearance on the hills and payments are strictly linked to actually doing the work. “There are no handouts, if you don’t to the work you don’t get the payments,” Trish is keen to emphasise.

These are clearly good things to be doing while a large part of the project will be training for all of the landowners on habitats and species. There will also be results-based habitats payments which deal directly with animal grazing.

This is crucial, as there are still too many sheep resulting in over-grazing the vegetation – something that is directly linked to the disappearance of the ring ouzel and the decline of other important habitats.

I specifically ask Trish and Mary about this; can we ease up on the animals, could we see a move away from sheep and back towards traditional cattle breeds (which are gentler on the vegetation while allowing trees and shrubs to develop naturally on steeper slopes), and what is the place for trees on the mountains?

“Yes, bringing cattle back to the hills is being trialled as part of the project” they tell me. In fairness three years is not a long time (and a budget of less than €1 million) for a project like this to produce results.

“The land will always need to be managed,” Trish asserts. “The question is how do we work the land”.

She talks about how cattle could be brought onto certain areas with electric fences to stop them wandering off, but this is the beginning of a process that has to involve the farmers every step of the way.

Given that there are only about 26 landowners across the whole mountain range and given the enormous problems of income inequality and an aging farmer profile, the questions she poses are indeed urgent if farming is to continue as a way of life on the hills.

“I’m going to be an optimist to the end… the most important thing to come from this project is the learnings, to get farmers sharing their knowledge again and being actively involved in shaping their future”. She recounts how she visited one farmer on his deathbed and how, just before he passed away, he took her hand and asked “will you take care of the mountain for me?”

Trish and Mary are doing what should have been done 20 years ago when the signs of rural and ecological decline first became apparent. I am impressed with their energy and commitment, and hope that their project can be successful. I am trying not to dwell on the opportunities which have been lost over the last two decades and which now leave a mountain to climb if we are to save critically endangered species like the ring ouzel.

We have little time to experiment and must move quickly not only to restore landscapes but to ensure that communities, not least the farmers, see the benefits of restoration so that they are at the forefront of these efforts.

We have to hope that in 2022, when the project comes to an end, that it doesn’t meet its end from budget cuts or myopic government bean counters. There will no doubt be lessons to be learned but it is already clear that bringing nature back without abandoning the land will involve local decision-making.

Where does that leave the Wild Atlantic Rainforest?

I don’t see how the creation of an enormous woodland is incompatible with the continuation of small family farms or even farming on hills.

Artwork credit: Jacek Matsiak

If we can have fewer animals, and a move away from sheep towards cattle, woodland will naturally regenerate on large areas which are not suitable for grazing.

We can do this in tandem with buying public land to expand national parks and nature reserves and switching from payments on sheep commonages to native woodland expansion. The rainforest doesn’t have to uniformly blanket the land – it can sit like a lattice on the countryside, interweaving through small farms and patchy open areas of hillside. The pieces are all in place. The saplings of the rowan trees are standing by.

In the next episode of Shaping New Mountains I look at my home city – Dublin, and wonder – can it be the Natural Capital? I hope you can tune in.

[i] Nelson E. C. & Walsh W. F. 1993. Trees of Ireland. The Lilliput Press.

[ii] Webb D.A. Some Observations on the Arbutus in Ireland.. The Irish Naturalists’ Journal, Vol. 9, No. 8 (Oct., 1948), pp. 198-203