Rewilding got a little closer to home this week with the announcement that the Affric Highlands in Scotland are to be added to the Rewilding Europe network. It becomes one of only nine landscape-scale projects (the organisation has many more smaller initiatives which include the Dunsany Estate in Meath) across the continent which include the Central Apennines in Italy and the Southern Carpathians in Romania (earlier this year we held a webinar with the manager of the Oder Delta project which straddles the border with Germany and Poland).

The Affric Highlands project builds upon the work of the Trees for Life project and its founder, Alan Watson Featherstone. It started rewilding the Glen Affric area over 25 years ago, mostly through the reduction of grazing pressure to allow the natural regeneration of the native forest. I visited (too briefly) in 2018 and it is stunning what has been achieved. The new collaboration with Rewilding Europe will see greater connectivity, more native woodland, restoration of bogs and the recovery of endangered species such as Wild Cat and Capercaille. It may even provide a site for the reintroduction of Lynx to Britain (incidentally, all of these species are native to Ireland but now extinct). It will be a fascinating project to watch and I can’t wait to visit again.

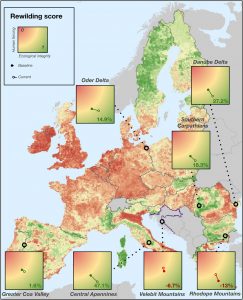

Rewilding Europe projects work at scale and are founded in partnerships with local organisations and landowners. The Affric Highlands project is the fruit of three years of consultations in the area and the approach is based on a long-term commitment. Apart from their beautiful communications material, the early monitoring work suggests that rewilding is working in its primary goal of restoring naturally functioning ecosystems. A study published last month showed that at seven Rewilding Europe sites, measures of ecological integrity were improving and that “overall progress along the rewilding scale” was seen at five of the sites. These improvements have occurred in less than a decade and point to the immense potential of rewilding to achieve long-term ecological aims.

The research comes on the heels of the recent adoption by the IUCN of a motion to establish “with urgency” a working group to develop guidance and principles for successful rewilding. It notes that rewilding is a “cost-effective approach to enhancing biodiversity, connectivity, ecological resilience and ecosystem service delivery” while stressing the need for “careful assessment of the relative risks and rewards to ecosystems and local communities affected by land-use changes”.

The lines show movement towards greater ecological integrity (green) (from Segar et al., 2021)

The Rewilding Europe network is just one initiative and there are many more projects where rewilding is happening in a directed, or more or less accidental way, across the continent and even here in Ireland. Randal Plunkett’s Dunsany project has received widespread media attention both here and abroad. Arguably the rewetting of Bord naMona’s worked out peat mines is rewilding through the restoration of hydrology in order to kickstart natural processes, particularly the prevention of carbon losses (and, maybe, carbon sequestration). But it’s sold as predominantly a climate action project that might have benefits for biodiversity. The nesting of a pair of Cranes on a former peat mine this summer, the first in over 300 years, on a bog that wasn’t even part of the rewetting programme, shows how nature will respond quickly and spectacularly to even passive rewilding. Imagine what would happen if we were to actually get behind rewilding at an official and policy level? Many ecologists in Ireland are currently afraid of even using the word, despite the desperate need for restoration of natural ecosystems and the growing body of evidence to show that rewilding works. How long can this go on?

So, I’m thrilled and excited for the new Affric Highlands project, but I’m frankly also envious and frustrated that we are so behind the curve in Ireland. The rewetting of peat mines, the recent release of more White-tailed Eagles and the Coillte Nature projects to convert plantations to native woodlands in Dublin, Sligo and Galway show that we can do these things, but we really need to be scaling up and we must shed the reticence to talk about the need for natural ecosystems (as opposed to enhancing nature on farmland, even if that is also needed).

So where should we start? Here are three places where I think should be working towards official recognition as Rewilding Ireland sites:

Ultimately we need to be thinking a lot bigger, eventually joining up these rewilding projects with others in every county and every parish. Who will be first the get the ball rolling?