Once upon a time there was a little boy who lived with his granny at Easkey. He always went down to feed the fish at the pier. He stole bread from his old grandmother for which she used to beat him, but still he did steal the bread and feed the fish.

One day in feeding the fish the sea was very rough and he fell into it and all the people on the pier could do nothing to save him. Then to their great horror they saw a large shark appearing which seemed to swallow the little boy. But it was not so; he did not swallow the little boy.

But to the great relief of all the people present the big shark swam to the pier and landed the little boy safely on the step unhurt.

Then the little boy ran home rejoicing and all that was looking on went home very thankful for the boy’s deliverance. They also learned a lesson that the great Maneater of the Ocean can return thanks for the deeds of kindness.

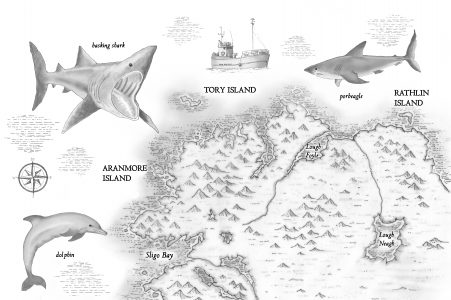

Artwork by: Naomi McBride

“If we do not make a place where the fish can grow and live, we will not see fish here. There will be a time when there are no more fish to catch. Our future generations will only see drawings of fish in a book”.

“First it was the salmon. Now we have lost the right to fish any type of fish. To get bait for our crab pots, we’re now forced to buy frozen fish caught by foreign trawlers. Like a baker who bakes no bread, we’re now islanders who fish no fish.”

These two quotes are both from island fishermen.

They tell a remarkably similar story of our rapidly changing seas – a story that has gone from plenty to scarcity, of ancient traditions disappearing, of a foreboding transformation in the vast oceans – at once lapping at our shores close to home, at once absent from our minds, our newspapers and our daily conversations.

Were they to meet, our two fishermen would, no doubt, have many stories to share. But they are worlds apart.

The first, Calixto Sinda from Amlan on the island of Negros in the Philippines; the second, a lament from John O’Brien from the island of Inis Bó Finne, off the coast of Donegal. Both men come from traditions where the sea runs like salt through their blood. They have seen their way of life vanish before them, the power they once had to make a living taken away from them – transferred to fewer, bigger boats by lobbyists and politicians who see little value in preserving places like Inis Bó Finne.

The endings to these stories have not yet been written, but on Negros in the Philippines the fishing communities are now authors of their own destiny.

In 2010 the community of Amlan and the marine ecosystem upon which it depends was “on the brink of collapse”. Commercial fishing, including the use of poison to catch fish and even dynamite blasting, was damaging the coral reefs despite falling within the Tandayag Marine Sanctuary. The sanctuary is small, only 0.06km2 and was designated in 1996. But drawing lines on maps without community support does not protect wildlife – something we know from painful experience here in Ireland.

But in 2010 an international environmental non-governmental organisation (an eNGO), RARE, moved in – not to boss the locals around and tell them what they had been doing wrong, but to work with local activists to facilitate better management of the reserve.

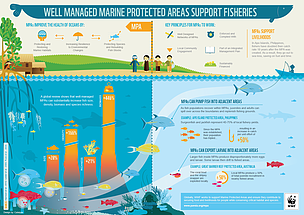

Local people were employed and government agencies were supportive, but crucially the local fishers saw they had a problem and could see the benefits of doing things differently. The community helped to design a reserve area where no fishing would take place. This allows space for fish to grow and spawn. The extra fish fry increase populations of fish which spill over into areas where fishing is permitted and so catches increase.

In 2018, working with scientists who identified their waters as critical recruitment zones for fish, the community themselves decided to more than triple the size of the reserve from nine hectares to 30 hectares.

According to one local official, “the community is vital to the success of the Marine Protected Area (MPA) because they are the ones who are there, so they are the managers… without the community it would not be successful”.

Image source: WWF

In 2019 RARE backed ‘Fish Forever’ projects in ten countries, mostly in the tropics, supporting one million fishers. Since the MPA at Amlan was managed, the amount of sealife has ballooned from a low of 13 metric tonnes in 2013 to nearly ten times that, 123 metric tonnes in 2016, only three years later!

The community no longer feels that this is a government programme or an eNGO initiative, but something that is theirs. Vice-president of the project, Steve Box, summed it up by saying “it’s not really about the fish. It’s about people, coastal communities, and fishing as a livelihood, a job, and a way of life”.

It’s a sentiment that John O’Brien and fishermen on islands around the coast of Donegal might agree with.

Ireland has a twin problem when it comes to sea. Firstly, the ecosystem has collapsed to such a degree that it only supports a tiny fraction of the marine life it once did.

Secondly, what remains is divided very unequally. Within the European Union’s Common Fisheries Policy Ireland gets a very small share of the catch and that catch is distributed (by the state) to a very small number of players. Following the Brexit trade deal between the EU and the UK, agreed on Christmas Eve 2020, Irish fishermen took another hit as the amount of fish they will be permitted to catch in UK waters will fall by up to 40%.

Meanwhile, MPAs cover a tiny extent of our seas, 2.3% at most, and none of these areas is subject to management measures. Ireland had already agreed to a target of 10% by 2020 while many scientists agree that this figure must be much bigger, more like 30% if we are to restore healthy seas. But why do we have to stop at 30%? Can’t we protect all of our seas?

Is it possible to catch marine creatures, support fishing communities and protect the seas at the same time? The answer should be: yes. But it will mean managing all types of fishing activity that goes on, something that simply doesn’t occur in Irish waters.

It will mean recognising that some types of fishing, like using ‘supertrawlers’ with nets the size of football stadia, dragging weighted nets across the sea floor or setting nets for a long time in areas known to be important for endangered species, are simply too damaging and need to end. It will mean setting limits for everything, not only the bigger boats but the smaller boats too and even low impact activities like sea angling and gathering seaweed.

Bottom trawling in the seas around Ireland is extensive and highly damaging. Image source: Marine Institute Ireland.

In 2020, new regulations were brought into force by then-agriculture minister Michael Creed which prohibited all trawling by boats over 18m in length within six nautical miles of the coast. It was to have ended the practice of ‘pair trawling’ for sprat by 2022. Sprat are a small fish that can shoal in big numbers and are the food source for everything from whales to seabirds to bigger fish. Pair-trawling involves two vessels dragging a fine-mesh net between them and, with no limit to how much can be caught, in the space of a few days the waters can be sieved clean, particularly in sheltered estuaries where the fish are gathering to spawn. It’s something that has been going on for years even in our MPAs such as Kenmare Bay, Donegal Bay and the Shannon Estuary.

That much of this fish was being churned up to make fishmeal, and so not even earning much for the boat owners, underlined the insanity of this type of fishing. When the consultation on the trawling ban was opened to the public, the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine received over 900 submissions. This was more than any response to a consultation from this department in relation to marine matters ever and small-boat fishers, anglers, environmental groups and ordinary citizens were united in supporting the ban.

The big fishing industry bodies – the producer organisations – were united in opposition, and later took legal action against the move. In October 2020 the High Court upheld their complaint, the pair trawlers were back in cleaning out the estuaries only days later, and the government later took the decision to appeal.

The new measures were important, maybe the most important we’ve seen so far, so it’s disappointing that they could not be supported by all fishermen. But even so, they don’t go far enough if proper management of our coastal waters is not put in place.

How can we go about reorganising our view of the sea? Can we empower local fishing collectives to manage their own areas, guided by scientists providing an evidence base with rules which are supported and enforced by state agencies?

The seas across the north coast of Ireland are cold and rich.

The basalt towers of the Giant’s Causeway are said to be the remains of a path built into the sea between Ireland and Scotland by the giant Fionn MacCumhaill. Fionn built the path to fight a giant from Scotland, Benandonner, but, according to the legend, Benandonner took flight and destroyed the causeway behind him.

Even today, giants can be found in these waters but these days they are less likely to be warring with one another. I once saw one while taking a boat to the Blasket Islands in County Kerry on a warm May day some years ago. We hadn’t gone to look for Basking Sharks but by chance someone spotted the triangular fin slicing through the water and the boat’s engine was cut.

As the shark approached, we could see its outline in the clear waters below, its cavernous mouth sieving the water for tiny food particles. They’re totally harmless of course, but you could see how earlier generations might have feared them, knowing little of their habits.

That we know anything about basking shark biology today is in large thanks to volunteer scientists in the Irish Basking Shark Study Group (IBSSG) who have been tracking and tagging the beasts since 2009.

Image source: Basking shark by Mike Brown

Emmett Johnston founded the organisation with Simon Berrow, better known for his work with the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group, after holding a seminar on the shark in Greencastle, Co. Donegal. Emmett went on to complete a PhD with Queens University Belfast looking at the shark’s movements, behaviour and connectivity in the North East Atlantic. Self-funded, or applying for grants here and there, the Irish Basking Shark Study Group now counts 15 scientists from home and abroad.

“We estimate that up to a quarter of the world’s basking sharks are moving through the waters off the north Ulster coast” Emmett tells me. “That’s a lot of sharks. And it’s not only basking sharks that use this productive sea area – it’s porbeagles, blue sharks, tope, minke whales, skates, maybe even angel sharks”. The latter is a critically endangered bottom-feeder with an Irish population now likely to be in the teens or low twenties. “It’s here that the colder, nutrient-rich waters flowing up the Irish Sea meet with the warm Atlantic swells. That triggers the seasonal phytoplankton blooms and creates a flow of energy right through the marine ecosystem, from small fish to sharks and whales and even humans”.

In 2015 the IBSSG invited Peter Klimley, also known as Dr Hammerhead and a world-renowned shark biologist, to visit Ireland. In 1999 Klimley wrote an article for Scientific American entitled ‘Sharks Beware’ in which he raised the alarm about declining shark populations across the world’s oceans. Comparing the vilification directed towards sharks following the massive success of Peter Benchley’s 1974 novel Jaws, and subsequent film of the same name directed by Steven Spielberg, to the reality of human rapaciousness, he presented a chronicle of decline of a number of species in the North-East Atlantic under the heading ‘Who’s Eating Whom’[ii].

He detailed the collapse of shark fisheries, something in which Irish and European boats participated in Irish waters, including porbeagle sharks (decline of 97% between 1964 and 1967) and basking sharks (decline of 93% from the 1950s to the late 1960s). Klimley spoke to a packed house in Dublin’s RDS and later visited Malin Head in Donegal.

“In global terms Ireland is not so famous for its terrestrial wildlife,” Emmett told me, “but Peter Klimley brought home to us what we are known for – being an island in the North Atlantic!” It sounds pretty obvious when it’s put like that, but the reality is Irish people are not all that engaged with the ocean that’s all around us. “Irish coastal waters stretch right out into the open ocean off the continental shelf and are some of the best shark habitats in the world!” he added.

If Irish people know little about the sea around us, even fewer of us are likely to be aware of its importance for sharks. Yet a remarkable 71 species of sharks and rays have been described from our waters.

In 2018 researchers from the Marine Institute, based in Oranmore outside Galway and using roving cameras at depths of 750 metres below the ocean surface, discovered a ‘shark nursery’ – a vast accumulation of shark egg cases. This was something never before seen in Irish waters and the researchers speculated that the female blackmouth catsharks gathered in this spot because it was a healthy coral reef, so providing protection for the young sharks upon hatching out of their leathery egg cases.

That’s right – a ‘healthy coral reef’ 750 metres under the sea off the coast of Ireland. The oceans are slow to give up their secrets but when they do, they are mind blowing. The video footage is remarkable.

A 2016 report from the National Parks and Wildlife Service highlighted how “Irish waters are of key importance to many of these species, hosting critical spawning and/or nursery aggregations”.

The nursery discovered by the Marine Institute scientists falls within a Marine Protected Area and so any remaining healthy coral reef is now safe from the bottom trawlers. The government report added that “moreover, these waters are the focus of some of the most intense fishing effort in Europe.”

As if to underline this point, and also in 2018, the Naval Service detained a Spanish-registered fishing boat off the south-west coast with a tonne of shark fins on board. It is estimated that this haul came from 5,000 individual sharks (possibly blue sharks but it’s hard to tell when the bodies are not attached to the fins) despite the fact that removing the fins of sharks at sea has been illegal in the EU since 2013. The fins were likely destined for Asia where shark fin soup is still considered a delicacy. In May 2019 the skipper of the Virxen da Blanca pleaded guilty in Cork Circuit Court and was fined €2,500 along with the forfeiture of catch and gear worth €165,000. That’s a fine of 50 cent per shark.

If sharks are remarkable for their beauty and their ancient evolutionary history, they are also remarkable for the degree to which they are threatened with extinction. Although in Ireland on average a third of all species are classified as ‘threatened’ or ‘near threatened’, when it comes to our sharks and rays it is double that. In Irish waters, it is exceptional for a shark or ray species today not to be on the way out.

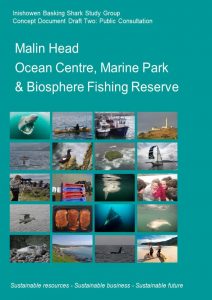

When Peter Klimley came to Ireland, he suggested to Emmet that a ‘Shark Park’ would be a neat idea for drawing attention to Ireland’s unique marine heritage while creating a protected area for endangered species.

To Emmet, the idea resonated: “we have National Parks on land to protect unique landscapes – why do we have none at sea covering our greatest natural habitats?” he wondered out loud. For such an idea to succeed, he added, would require “really good buy-in from local communities”.

Emmet and his colleagues set about drawing up a proposal for a ‘Malin Head Ocean Centre, National Marine Park & Biosphere Area’. It had two main components: a visitor centre at Malin Head, along the Wild Atlantic Way, to showcase Ireland’s exceptional marine biodiversity and an ‘integrated marine zone’ which would be Ireland’s first National Marine Park encompassing offshore islands and existing protected areas along with surrounding areas of ocean.

The plan they produced is remarkably detailed and thought-through. It was costed (€1.3 million for the interpretive centre, cost neutral for the marine protected zone as the state already owns the islands and seas) and set out a timeframe for delivery (2014–2020).

It highlighted how tourists tend to spend only half an hour at Malin Head, Ireland’s most northerly point, with the main attraction being a derelict signal tower. It described the unemployment and brain drain and how “there is no plan for job creation north of the Derry/Letterkenny road” but the tone was upbeat:

“Achievement of this proposal will transform Malin Head, one of Ireland’s remotest socially deprived areas with traditionally low levels of employment and education into a viable community with a sustainable future operating in relative harmony with their surrounding natural environment”. There would be direct employment in running the centre as well as research and management posts for the marine protected area as well as secondary jobs in low-impact ocean-based tourism – kayaking, deep sea diving and the like.

waiting to be implemented

The report also acknowledged that the traditional fishing industry is on its knees. It’s a legacy that’s not so easy to shake off.

“People here see themselves as from fishing communities even though many of them don’t actually fish. In reality, the coastal communities have been devastated, the vast majority of fishing in local waters here is potting for crabs and lobsters – and they’re not even fish” Emmett said.

The idea for the Marine Park was not only centred on the fact that the waters off Malin Head are among the best in the world for viewing basking sharks but would require engagement and buy-in from the local fishing community.

This would depend “entirely on community desire, engagement and agreement”. As such the project envisaged a ‘voluntary conservation area’. Emmet related a story about how in the early 2000s the local fishermen at Greencastle had initiated one of Ireland’s first ‘no take zones’ for juvenile cod, which was being overfished at the time. In theory this would have allowed both the local and regional cod population to recover, but the locals and even the Irish state found it difficult to stop boats from outside the area coming in and taking what they wanted.

When Emmett approached the locals with his Marine Park idea, he said they were understandably cautious but open to it. He told me that it would be possible to have a managed area that would allow the establishment of a more locally focused sustainable fishery, while protecting the sharks and other marine life.

According to Emmett “Many of the larger shark species are seasonal visitors and when here, they aggregate close to the shore at rocky outcrops or wrecks located in strong tidal streams. These places are already difficult for the larger trawlers to deploy their fishing gear in, so it may not be such a big loss of fishing area to set these aside for conservation. Also our research is starting to provide valuable information on shark behaviour, for instance basking sharks mainly feed at the surface only during the day, at night they swim at greater depths – so a simple method to avoid sharks getting entangled as bycatch could be to fish surface waters at night. Also, the basking sharks are particularly susceptible to collisions with boats, so we could use boat speed limits and broadcast radio warnings to skippers at certain times of the year when the sharks are more likely to be on the surface. If anglers want to target blue sharks or other species then there’d need to be protocols on catch and release and proper training provided on shark handling. These are fairly sensible approaches that would allow people to continue to make a living or enjoy their pastimes while being genuinely conservation-centred”.

As the sharks move across the north Irish coast, and on into Scottish waters, Emmett envisaged a much larger transnational Shark Sanctuary stretching across this corner of the North Atlantic. But the national support is missing. “Developing countries have been much better at implementing coastal zone management. Here – it’s either no government support at all or a top-down heavy hand approach is taken, either way – we have made little progress with regard to practical shark conservation or for that matter, the conservation of Ireland’s wider marine-based biodiversity” Emmett concludes.

In August 2014 researchers tagged a female basking shark off the coast of Malin Head with a radio transmitter. However, after a few months, the transmitter malfunctioned and stopped sending signals. These gadgets are expensive and so few of them are deployed. Sometimes they malfunction and that’s the end of the story.

But this time, three years after the tag was first attached, the shark was photographed by a diver… 4,600km from Malin Head, off the coast of Massachusetts in the USA. Thanks to social media, the photo did the rounds and the tag was identified by scientists from Queen’s University in Belfast.

It was only the second time ever that a basking shark was tracked across the Atlantic Ocean and the discovery “completely changed the way we think” said one of the researchers. There’s still a lot that is not known about these mysterious behemoths.

They appear in the waters off Ireland and Scotland in spring with the appearance of blooms of phytoplankton, clouds of tiny plants which colour the waters green. The sharks sieve tiny plants and animals from the water through their enormous mouths. But no one knows where they go or what they feed on in winter, then the phytoplankton dies back, in just the same way that the leaves of plants on land fall to the ground in autumn.

Some think their giant livers, which are full of oil and so are stores of energy, get them through the lean months, but no one knows. That they are ocean wanderers had been suspected and the sharks off the coast of Ulster have long been considered as part of the same population as those off the west coast of Scotland, which should hardly be surprising given that it’s the same body of water that just happens to be fringed by countries in different national jurisdictions.

In July of 2019 the Scottish Wildlife Trust the and UK’s Marine Conservation Society launched a campaign to designate a massive area of ocean around the Hebridean Islands as a Marine Protected Area, with the designation principally aimed at protecting the globally important numbers of basking shark and minke whales which appear there over the summer months.

However, while the proposal sounds positive, it was criticised at the time for failing to explain how the MPA designation would actually help to restore the basking shark population, which is now endangered with extinction throughout its global range (and decreasing).

It was not the first attempt to protect sea life in this part of Scotland and the seas are already a layer cake of legal protections with bureaucratic titles including Special Area of Conservation, Sites of Special Scientific Interest, Local Scenic Areas and Special Protection Areas. One of these Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) – the Sound of Barra – straddles the waters between the island of Barra, 175km north of Malin Head, and its larger neighbour to the north, South Uist, along with the smaller Isle of Eriskay.

The SAC was first proposed for designation in 2000 under the strict rules set by the European Union’s Habitats Directive and it immediately faced fierce opposition. Someone who was on Barra as this drama unfolded was Dr Ruth Brennan, now a senior research fellow at the Trinity Centre for Environmental Humanities in Trinity College Dublin.

Ruth told me that “Under the rules of the Habitats Directive, only scientific criteria could be considered when proposing the SAC’s boundaries, which led to the situation that when representatives from government agencies visited the islands to consult with local people about the proposed designation, they could only ‘take note’ of the social and economic concerns. The Scottish government could not take them into account when making the decision to designate – something which infuriated many of the locals. The Habitats Directive became a major hindrance to the implementation of conservation measures as it created this artificial separation between people and nature”.

There was good reason for this in fairness. It was felt at the time that were social and economic considerations allowed, then these would have been used to dilute protections. But it also has to be acknowledged that the system of nature protection designed by the Habitats Directive, despite its strong points, has been an abject failure in Ireland.

When the outline of a management plan for the SAC was brought by Marine Scotland (the state agency leading the process) to the Barra islanders for discussion the message was simple – we’re prepared to engage if we can lead the process, not if we only have a seat at a pre-determined table led by government agencies.

Marine Scotland returned with a blank sheet of paper, laying the foundation for a community-led, co-management process in which the various parties could participate. Nevertheless, despite all the wrangling, a management plan has yet to be agreed, 20 years after the lines of the SAC were first drawn and seven years after it was legally designated.

Ruth brings an alternative perspective and one which is undervalued in the world of nature conservation. She describes herself as a marine social scientist, but as we walk across the cobble covered expanse of Trinity’s 16th-century Parliament Square late on a November afternoon, I learn that she is much more than that.

She studied law, also in Trinity, and was a solicitor of the Supreme Court of England and Wales before heading to Central America to be a dive master. In 2007 she completed a Masters Degree in Coastal and Ocean policy in Plymouth University in England before heading to the Scottish Association for Marine Science and University of the Highlands and Islands to work as a researcher and do a part-time PhD entitled “What lies beneath: probing the cultural depths of a nature conservation conflict in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland”.

In 2016 she even found time to devise a marine litter strategy in Jisr-al-Zarqa, an Arab-Israeli coastal village. Ruth describes her work to me as “making values, norms, worldviews and power relations visible. People tend to imagine traditional views of our relationship with nature as linear, for example, that people impact nature, or people receive benefits from nature. But it’s not linear, we interact with the natural world in a complex way that is much more interdependent”.

While on the island of Barra, a five-and-a-half-hour ferry journey from the Scottish mainland, she witnessed first-hand the tensions between many of the islanders and their traditional relationship with the sea, and government-led initiatives to promote nature conservation.

Scottish Natural Heritage, the agency in Scotland equivalent to Ireland’s National Parks and Wildlife Service and known by its acronym SNH, was mockingly referred to by some as ‘See No Humans’.

Meanwhile the people of Barra were portrayed in certain media articles as being ‘anti-nature’ in their opposition to the proposed SAC. “My research explored how the highly-charged word ‘conservation’ has different meanings depending upon who you’re speaking to,” says Ruth. “Many of the islanders I spoke to perceived the government’s understanding of conservation as ‘hands off’… ‘draw a line around’… ‘keep out!’, while to many of the islanders conservation meant ‘hands on’… ‘live with’… ‘use wisely’”.

The islanders have a very long and intimate knowledge of the sea and when SNH drew the lines around the Sound of Barra SAC it appeared arbitrary to many islanders and without recognition of the culture of the area, where people and nature had been intertwined for generations.

“The policy approach to conservation dictated by the Habitats Directive, which SNH and the Scottish government were obliged to implement, didn’t reflect the lived experience of many local people”.

One of the projects Ruth worked on, together with visual artist and film-maker Stephen Hurrel and members of the Barra community, was an art-science-community collaboration called Sea Stories. An online, interactive cultural map of the sea around Barra, Sea Stories gathered and recorded some of the names, stories and cultural knowledge of the sea around Barra’s shores, which are rich in meaning and intangible heritage. The map explores the intimate relationship between people and place, making visible the rich cultural knowledge that exists in the sea around Barra. You can see it on mappingthesea.net/barra/ .

This intimate knowledge of places is something which has been lost to a great degree in Ireland. An RTÉ documentary in 2018 explored the words for place and nature in the Irish language including the lexicon surrounding seaweed with the abundance of traditional names which, it turns out, are matched closely to the more modern application of scientific taxonomy.

Fishermen had names for points in the ocean such as Fochais na nDeargán – the submerged rock of the sea bream – or Lag na mBodagh – the hollow of the codling – which are now all but lost as we’ve distanced ourselves from the elements and the creatures which inhabit them.

Seán Mac an tSíthigh, who featured in the programme, spoke of how “extreme attention was paid to the subtleties of the landscape… we only have the surface of the tradition remaining today and especially with the transition that’s happened in terms of fishing and farming you don’t have people as active on the land or at sea as they would have been. Nowadays the lobster fishermen, who are doing it commercially, they’re using radar to find the fishing grounds. They’re not using the old indicators of the place names or even the weather signs, they’re using modern technology. And because of that they don’t have the intimacy with every crack and every rock as the lads in the naomhóg [the traditional open row boats] would have had 50 to 60 years ago.”

Ruth tells me how the connections between science, art and cultural heritage are essential to articulating the complexities of the human-nature relationship. It’s a long way from how we currently manage human activities in the sea.

“The ‘Our Ocean Wealth’ plan [produced by the government in 2012, and with its pictures of dolphins and coastal scenery] was largely focussed on the economic benefits, goods and services provided by the marine environment to the exclusion of other ways of understanding the sea and human-nature relationships. We have to widen the lens. There is also an issue of social justice. When one way of framing an issue dominates over others – we need to ask, who is being marginalised by this framing and why? Who is influencing and making the decisions and who do these decisions serve?”

Ruth’s current project is helping to design new ways to manage small-scale fisheries on the Irish islands in a way that highlights and promotes marine stewardship. To this end, she is working closely with the Irish Islands Marine Resources Organisation, which counts among their members fishing men and women from islands of Cork, Galway, Mayo and Donegal.

Ruth says “Islanders are trying to challenge the current set up. They may be few in number but fishing is central to their identity”. I ask her if she thinks islanders are willing to engage with the process to create Marine Protected Areas – “oh yes” she replies “but they probably won’t do it as an Irish Wildlife Trust project [referring to the organisation I work for], they’ve been working on their own MPA project for several years. So it’s far more likely that they would do it as an islands project. They’ll do it if they can own it”.

Talk of ‘no-take-zones’, where all extractive activity is prohibited, would probably be a no-no for them. “Coastal communities need to be in the driving seat” she says.

I agree with Ruth that the islanders must feel a sense ownership over the MPA process if it is to work, but I also feel we need to have no take zones, if only so we can see what the sea would look like were all commercial activity to cease. There is also good evidence to show that no take zones can benefit fishing communities, as fish and crustaceans multiply and spill over into areas where fishing is allowed.

The fishing industry is currently a mess. Despite promises of reform, overfishing remains a prevalent feature of commercial exploitation of many fish species. While the awful impacts of plastic in the oceans have exploded in the public consciousness, the fishing industry remains by far the greatest impact on marine ecosystems. Even where plastic is concerned, a study by environmental campaigners Greenpeace found that the fishing industry is responsible for most plastic litter at sea with 640,000 tonnes of nets, pots, traps and ropes dumped every year[iii].

Most marine litter is from fishing

Because this stuff is designed to catch and kill marine life, referred to as ‘ghost gear’ when it has been discarded, its effects are far more deadly than straws and the lids of disposable coffee cups, which rarely make it to the sea in any case.

Although the European Union will say that it has a strict system of regulation when it comes to commercial fishing, with its quotas and ‘total allowable catches’, in fact there is virtually no supervision of this system.

In Ireland, state agencies have a target of monitoring a mere 1% of all fishing trips – that is, having independent observers on board to document things like the unwanted ‘bycatch’ of protected species – but this is based on the voluntary acquiescence of boat owners and, not surprisingly, few are willing to be supervised. We therefore don’t even meet this meagre 1% target.

In 2018 a report by the European Commission auditing Ireland’s control and monitoring of fishing activity found “severe and significant weaknesses” with a lack of “effective” enforcement and penalties.

It highlighted in particular how inspections at Killybegs, Ireland’s largest fishing port, checking the size of fish-holding tanks and cross-checks with reported landings were done on pieces of paper rather than electronically, and so preventing any coherent monitoring at a national level.

It highlighted how “the enforcement and sanctioning system in Ireland is inadequate, with the apparent lack of follow up of suspected infringements by the [Sea Fisheries Protection Authority] and a lack of effective, dissuasive and proportionate sanctions applied” and that there were doubts regarding the official landings of key fish species such as mackerel due to the “manipulation of weighing equipment”.

Back in 2013, following a massive public campaign led by celebrity chef Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, the EU was set to ban the practice of dumping dead or unwanted marine life overboard – an appallingly wasteful practice. But a ‘compromise’ was agreed that this would only apply to commercially valuable species, leaving everyone to figure out how those species would be separated from the mass of biology scraped off the seafloor and dumped on a ship’s deck. As a result, the practice continues unabated.

And then there’s the issue of human rights abuses and allegations of slavery and human trafficking that have dogged the Irish fishing industry for some years now. One media report suggested that 25% of people trafficked into Ireland were destined for fishing boats and despite there being 64 confirmed cases of human trafficking in 2018 there have been no prosecutions.

Kevin Hyland, who was the UK’s anti-slavery commissioner and who received an OBE for his work, said: “I’ve met some of these fishermen and it’s terrible, their treatment is shocking. And again, there’s never been a prosecution [in Ireland], there’s never been any action.”[iv]

A 2017 report from the Department of Justice and Equality highlighted how in November of that year 12 Indonesians were found working “in very poor conditions” on a Spanish-registered fishing vessel docked in Castletownbere in Cork while it also stated that “concerns persist in relation to the exploitation of non-EEA [European Economic Area] workers in the Irish fleet.”[v]

Meanwhile the US State Department has downgraded Ireland to ‘tier 2’ in its efforts (or lack of them) to combat human trafficking noting that “the government did not convict any traffickers under the anti-trafficking act; there were no convictions under this law since it was amended in 2013”.

Ireland standing out. Image source: US State Dept.

All the while the ocean ecosystem comes under increasing strain. Not only is it being overfished and polluted with the detritus of humankind, it is also acidifying from the absorption of elevated carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere (which dissolves in water to form carbonic acid) and it is running out of oxygen.

In 2019 the International Union for the Conservation of Nature warned that “Ocean regions with low oxygen concentrations are expanding, with around 700 sites worldwide now affected by low oxygen conditions – up from only 45 in the 1960s. In the same period, the volume of anoxic waters – areas completely depleted of oxygen – in the global ocean has quadrupled”.

Warming of the oceans is contributing to the depletion of oxygen while the rising sees are set to indiscriminately engulf coastal towns and cities, from Waterford to Shanghai by the end of the century.

Ruth Brennan is working with the small-scale island fishermen for their right to fish for a fair share of the catch in their waters. They are largely locked out of the quota system of the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) meaning they are predominantly left with ‘non-quota’ species.

No long permitted to catch salmon, this means crabs and lobsters, hence the fishermen no longer catch fish. The system as it stands is unfair and Ruth points out how the most valuable species end up in the hands of very few. For instance, it has been alleged that 91% of the Atlantic herring quota has been allocated to 23 large boats, owned by a mere 18 individuals.

Under the CFP, island fishermen fought for, and won, special recognition. One clause specifically allows national governments to provide incentives to these fishing communities to reduce their environmental impacts, whether through reducing energy use or alleviating damage to habitats. In 2014, the Irish government was advised to examine the feasibility of issuing ‘heritage licences’ to small-scale, low-impact fishers.

On foot of this, the Island Fisheries (Heritage Licence) Bill was brought before the Dáil in 2017 seeking a pretty modest 1% of annual fishing quota for species such as mackerel, which was worth over €200 million to Irish supertrawlers in 2019.

Among the communities that would benefit are the fishermen of Arranmore, off the coast of Donegal.

The islands have always been romanticised as repositories of the Irish language and culture, even as we’ve watched them decline, but it’s nevertheless hard to resist their charm. With mass migration to the towns and cities it’s a wonder we have anyone left on the islands at all and you’d think we’d be throwing the kitchen sink at maintaining their unique identity.

That means not only tourism, which is obvious enough, but other forms of employment, and above all – fishing.

I have visited many of the Irish islands over the years but until I stepped off the ferry from Burtonport in late July of 2019, I had never been to Arranmore. The day before I had addressed the MacGill Summer School in Glenties, a festival of mostly political thought which has been running since the early 1980s, and I had spoken to the audience about our extinction crisis.

It seemed like an apt location to be driving the message home. The emptying of the oceans and the inequality driven by global commodity markets have been most apparent in coastal communities like those on Arranmore. In 1898 it had 60 boats fishing for herring from its harbour, while harvesting kelp was a significant occupation. There were no fewer than four herring curing stations on the island at that time as well as the lucrative salmon fishing. Today there are 15 small boats, mostly potting for crustaceans[vi].

I get a coffee in the café in Burtonport while I wait for the ferry. The building is new but there are sepia photos on the walls showing women sorting through great heaps of herring, a scene of bygone days.

The days of plenty

It’s a short crossing to the island. The ferry has colourful paintings of sealife on the walls of the small waiting room, but it’s too nice a day to be inside. From the deck, a seal eyeballs me as we leave the harbour and a little further out a dolphin briefly breaks the surface, slowly arching its back before disappearing under the swell.

Seamus Bonner meets me off the ferry with a smile and a handshake and brings me to the island’s newly opened innovation centre a stone’s throw from the harbour. Telecoms company 3 have recently installed superfast broadband as well as enhanced 4G wireless internet. The company is promoting new technologies which includes not only fast internet for all the islanders, but the ‘internet of things’: sensors on buoys so fishermen can more easily locate their pots at sea as well as monitoring water quality in holding tanks for crabs to ensure they are maintained in optimal condition before sale.

It’s a forward-looking project for an island which has suffered from emigration and decline for many decades. Nevertheless, I find an island that is full of young people staying for a few weeks to improve their Irish (Arranmore is a Gaeltacht destination) as well as a group of radio enthusiasts gathered at the far end of the island around a cluster of antennae leaning into the Atlantic Ocean.

Arranmore is twinned with Beaver Island in the USA and at its north-western end there’s a roadside statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary overlooking a pond with a stone circle flanked by an otter and a beaver. A sign pointing west indicates 2,750 miles to the Great Lakes.

Seamus is bringing me on a drive around the island and explains that many of those who emigrated from Arranmore found themselves on Beaver Island, which sits at the northern end of Lake Michigan, near the US/Canadian border (Beaver island’s main thoroughfare is called Donegal Bay Road in recognition of the historical connections).

Nearby, choughs (a type of coastal crow with jet black plumage and a scarlet, scimitar-shaped bill) alight on the short turf. The cliffs here form a protected area for them along with other seabirds. We see a raven ride an updraft, hovering motionless as it stares down at the choppy waves. The vastness of the ocean lies at our feet. I joke with Seamus that he could push me off and no one would know to look for me here.

Chough. Image source: Mike Brown

Seamus is the secretary of Arranmore Island Community Council but fishing is in his blood. “My family has been living on the island since at least the 1800s. We were involved with mixed farming but mostly fishing. It was seasonal, there’d be herring in October, followed by crabs over the winter, then mackerel, as well as salmon.

Growing up, everybody was involved, but industrial fishing has changed everything. It’s been a slow decline, but the loss of the salmon in the late 2000s was an especially hard blow” he says.

He has been lobbying national politicians to promote the Island Fisheries Bill, which he says would allow access to fishing quotas to be divided amongst the islands every year, enabling seasonal fisheries around the islands.

He tells me that “small boats in Ireland of less than 12m in length make up 86% of the fleet yet we only get 0.85% of the quota, how is that fair?”

But they met with opposition from the government at the time, which used a spurious ‘money message’ to prevent the bill progressing[vii]. Seamus is scathing of the inertia in the civil service and the lengths the state will go to in preventing equitable access to fishing quotas.

He points to the hundreds of tonnes of fish which are caught in supertrawlers in a single pass. Sometimes these fish are not even caught for human consumption but are ground down into fishmeal or go for pet food.

He also notes that EU rules allow for special support to be given to island and rural communities but the Irish government hasn’t followed through. But while Seamus is wistful he is also imagining how things can be different.

“These days it’s very hard to eat locally caught fish” he says, “we want to develop a system that puts the fishermen more in control of their earnings, by catching fish on demand for sale directly to local restaurants where we can capture a premium price. And we’re working on developing technologies, such as phone-based apps that link the fish all the way through to the customer – people will see where their money is going”.

Seamus and some of the island fishermen made a trip to Galicia in north-western Spain to see how managed areas for fishing work in practice. It involves scientists and government agencies supporting fishermen in setting limits to how much fish is caught.

It’s a system that benefits the environment as well as providing better, more stable incomes for the fishermen. “We saw there that it’s not all confrontation, but enforcement is key” he says.

It sounds a lot like a Marine Protected Area and I ask Seamus does he see a role for fishermen in protecting marine life here in Donegal. “There is nervousness here about MPAs” he replies, “no-take zones would wipe out the fishing communities – we feel we have to be part of the management.” I ask him about seals as calls for a cull are an on-going feature in the fishing press. He smiles back at me. “Seals are small-scale fishers – just like us. We’re happy to share the sea with them, there should be plenty to go around”.

I’ve brought my bike, and after leaving Seamus I cycle around the island. I underestimate how steep the climb is to the northern side, pumping sweat in the lowest gear as I again pass the lake with the stone beaver and otter, before hurtling down the unswerving, potholed road that leads to the lighthouse.

On the return leg, I’m halfway back to the harbour, enjoying the breeze and the views to the Donegal mainland as I roll down the hill, when I realise I’ve lost my car keys so I have to stop and labour up the hill again, now in a nervous sweat that I won’t find the keys and I’ll be goosed.

Thankfully I find them in a spot near the road where I had earlier tumbled off the bike on the slippery grass, evidently the keys had fallen out of a side pocket. Now I’m looking at the time and realising I have to hurry back to catch the ferry. I’m a perspiring mess as I wheel back to the south side of the island, and before leaving, gasping, I call into the local shop for a cooling Iceberger.

The teenagers are eyeing me, wondering if they need to be concerned. I regain my composure, and while I’m there I pick up a bag of locally harvested dulse, a seaweed. It’s been harvested on Arranmore and coastal areas like it for centuries, probably millennia. It’s a little salty as a snack but I later discover it’s phenomenal when steeped in steaming vegetable stock and poured over ramen noodles. If nothing else, a visit to the islands is always an adventure.

What does the future hold for island and coastal communities like Arranmore? Are they destined to decline remorselessly, to be abandoned like so many islands before them?

Will a combination of fiercer winter storms and dwindling sealife leave summer tourism as the only source of economic life? We have to hope not. We have to hope that nature still has the potential to heal itself if and when we decide it is worth restoring.

We have to also hope that a fairer system can be devised for sharing what we take from the sea so that ancient connections can be maintained. If we can make these connections, the Ulster Shark Coast can benefit some of the largest and most charismatic creatures in the sea, as well as the people who depend on it for their identity.

Artwork by: Jacek Matsiak

[ii] Klimley P. American Scientist. Nov-Dec 1999. Vol. 87. No. 6. Pp 488-491.

[iii] Ghost Gear: The Abandoned Fishing Nets Haunting Our Oceans. Greenpeace Germany. November 2019.

[iv] Over 60 confirmed cases of human slavery in Ireland in 2018 – but no criminal convictions. By Lix Farsaci. Irish Mirror. November 23rd 2019.

[v] Trafficking in Human Beings in Ireland. Annual Report 2017. 2017. Department of Justice and Equality.

[vi] Ferriter D. 2018. On the Edge. Ireland’s Off-shore Islands: a Modern History. Profile Books.

[vii] A ‘money message’ is an obscure procedure that allows the government to block legislation if it feels it requires tax and spending measures. The minority Fine Gael government was criticised for over-use of this mechanism to block the progress of legislation it didn’t like. At the end of 2019 Opposition parties were accusing the government of stalling over 50 bills in this way from the legalisation on the use of medicinal cannabis to climate emergency measures.