by Pádraic Fogarty July 23rd 2022

Hundreds of records released to Coastal Concern Alliance, a citizens’ group, under Freedom of Information and Access to Information on the Environment rules raise serious questions for habitat protection and wind farm development in the Irish Sea

Sandbanks are an important habitat which are listed under Annex I of the EU Habitats Directive. They are defined by the EU as “elevated, elongated, rounded or irregular topographic features, permanently submerged and predominantly surrounded by deeper water. They consist mainly of sandy sediments, but larger grain sizes, including boulders and cobbles, or smaller grain sizes including mud may also be present on a sandbank.”[1] The EU says they are “seldom more than 20m” below the water surface (technically, this is referred to as ‘chart datum’).

Sandbanks are listed for special protection for a number of reasons. According to the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS), they contain unique communities of invertebrates while the sandy substrate is home to sand eels, a small sliver of a fish that gathers in shoals and which are an important food source for sea birds such as terns.

Like sand dunes on land, sandbanks are dynamic systems, constantly shifting with the waves and currents. In this way the sand on the sandbanks is connected to the sand on the shore and the dunes behind the shore. The wind and water are constantly moving this sand around, blowing particles inland, dumping sand from the sea onto the shore and washing sand from the shore back out to sea.

Research has shown that large sand banks protect the coastal areas from wave power with one study stating that “removing, lowering or raising a headland-associated sandbank can have a significant impact on longshore sediment transport”. In other words, offshore sandbanks play an important role in protecting the coast from weather extremes and in particular from coastal erosion.

So, sandbanks are important for wildlife but also serve a very practical purpose in protecting our coastal infrastructure. The vast majority of sand banks around the Irish coast are located in the Irish Sea and this is perhaps not surprising given the expanses of sandy beaches that can be seen to stretch from County Wexford in the south to County Down in the north.

When the Habitats Directive became law in Ireland in the late 1990s, Ireland had an obligation to designate a representative sample of our sandbanks within Special Areas of Conservation (SAC).

Sandbanks are important feeding areas for birds such as Arctic tern (c. Mike Brown)

Habitats Directive – based on science

By 2012 the EU required that the area of sandbank to be designated should be somewhere in the range of 20-60% of the national resource while also making sure that there was a good geographical spread. There is a very clear stipulation in the Habitats Directive that the designation process must be based only on science. Objections to the designation must, similarly, only be based on scientific grounds; socio-economic concerns were not to be entertained, even though socio-economic activities could be undertaken so long as they didn’t affect the long-term integrity of the habitat or species for which the SAC was designated.

This is relevant to our story because, following on from the EU Biogeographic Seminar held in Galway in March 2009, the EU was pressing Ireland to designate more sandbanks as SACs in order to fulfil our legal requirements. At this time, wind energy companies were interested in developing offshore projects even though, to-date, the only offshore wind farm in Ireland is a seven-turbine facility on the Arklow Bank, off County Wicklow, which was commissioned in 2004.

In 2011 the total area of sandbanks off the Irish coast was calculated to be 519km2 and, although there were small areas of the habitat off County Donegal and in the mouth of the River Shannon, the vast bulk were strung out in a line from north County Dublin to Carnsore Point in County Wexford. Meeting the requirements of the Habitats Directive would have required designating many of these sandbanks as SACs. However, this is not what happened.

Today, there are just four SACs for sandbanks in Ireland: one in County Donegal (Hempton’s Turbot Bank), one off the north coast of County Kerry (a part of the Lower River Shannon SAC), and two off County Wexford (Long Bank SAC and Blackwater Bank SAC) which share a boundary and so are effectively the same area.

Despite a vast expanse of suitable habitat, there is not a single sandbank SAC north of Cahore Point in Gorey, County Wexford, where the Blackwater Bank SAC comes to an end. Why?

Citizen investigation

For the past two years, a citizens’ group, Coastal Concern Alliance, has retrieved hundreds of records through Freedom of Information and Access to Information on the Environment legislation from the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage and the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine. Having received an initial release of records, they appealed the decisions, initially, to a more senior level in the Department and, subsequently, to the Office of the Information Commissioner and the Office of the Commissioner for Environmental Information. The IWT has been given access to these records and has spent some time studying them.

What has been found to-date raises questions about the current level of protection for sandbanks in the Irish Sea and the future for wind energy developments in this area.

Serious questions are also raised for the two government departments about how they handled the designation (and non-designation) of SACs in the period from 2010 to 2013 and particularly whether there was political interference on behalf of the wind industry in what should have been a process based purely on scientific evidence.

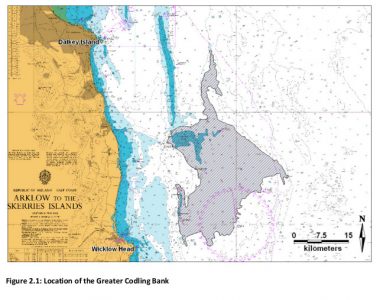

Codling Bank

One of the largest sandbanks in the Irish Sea is the Greater Codling Bank off the northern coast of County Wicklow. Its area is given by the NPWS as 231km2, nearly half of the total area of sandbanks in the country. This is significant as, in order to meet the Habitats Directive requirement of protecting between 20-60% of the national resource, designations of SACs covering from 104-311km2 was needed.

The Greater Codling Bank

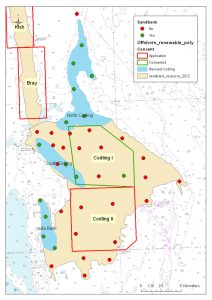

In order to achieve this, the NPWS proposed to designate the Kish/Bray Banks (which stretches north of the Greater Codling Bank), the Blackwater Bank off County Wexford and Hempton’s Turbot Bank off County Donegal, in addition to those which had already been designated.

A 2007 survey of these sandbanks found that both the Kish/Bray Bank and the Blackwater Bank sites met the criteria for designation and were “nationally important features”. It also found that the Kish/Bray Bank was a “richer habitat” than the Blackwater Bank[2]. This is not an incidental detail, as we’ll see later.

However, in January 2012, in a memo to Fine Gael Minister Jimmy Deenihan (who oversaw the NPWS at that time) it was highlighted that:

“The Irish Offshore Operators Association (who represents the offshore renewables industry) has previously expressed concern that too many sandbanks in the Irish Sea are being designated and this may impact on their industry”

Then, in March 2012 the NPWS gave a presentation to officials from the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine and the Marine Institute. The minutes from this meeting state that:

“Designation of SACs inshore or deep water is within the competence of a MS [Member State] and is subject to a 3 month national consultation process where objections can only be from a scientific perspective. NPWS intent [sic] to proceed with this in the next few weeks. […]

At a later stage when the broader management and conservation objectives are being set they then have to consult with all national and international stakeholders. […]

NPWS seem reluctant to bring this up at the Marine Co-ordination group despite the urgings of Peter Heffernan [then-director of the Marine Institute] – probably not wanting the political battle in advance of designation” [our emphasis].

The Marine Coordination Group was established as part of the ‘Harnessing Our Ocean Wealth’ Plan which was an initiative of then-Fine Gael Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine, Simon Coveney. The record suggests that, despite emphasising the requirement for a scientific basis, the NPWS somehow felt that designating SACs would be a “political battle”.

The following month, April of 2012, with Minister Coveney in the chair, the NPWS outlined the plans for new SAC designations, including the Kish/Bray Bank and the Blackwater Bank, to the Marine Coordination Group.

Then, in May of that year, a month after the presentation to Minister Coveney, a tender request was issued for a survey of the Greater Codling Bank.

The survey was completed over two days in July 2012 and the report, published in October of that year, stated that “the sediment sampled from the Greater Codling Bank was classified as sand, slightly gravelly sand, gravelly sand and sandy gravel”. It also reported that “a gravelly/cobbly seabed dominated the Greater Codling Bank”, which seems to contradict the first statement. The report made no assessment of, and drew no conclusions about, the habitat in terms of its quality or compliance with the EU definitions of sandbanks[3].

Nevertheless, the records released to Coastal Concern Alliance show that in November of 2012 a note from the Head of the NPWS Scientific and Biodiversity Unit stated that the Greater Codling Bank was no longer classified as a sandbank and so was to be removed from the overall calculation of the national sandbank resource. This record was not accompanied by an explanation as to why this should be the case.

The rationale for the removal of the Greater Codling Bank from the national resource of sandbanks is not explained in any of the records released to Coastal Concern Alliance, nor has any consistent, valid explanation been provided in response to questions put to the NPWS in writing and verbally.

Was it because the survey found that sea bottom was dominated by ‘gravelly/cobbly’ material? While this contradicts earlier statements in October 2012 report, it would not rule out identifying the habitat as sandbank according to the EU definition. Even so, if this was the rationale, there is no evidence that such an argument was put forward.

In June 2022, Coastal Concern Alliance commissioned a scuba diver to visit one of the points sampled for the Greater Codling Bank survey and found plenty of sand (the video is here). Indeed, the Greater Codling Bank is still listed on the NPWS website as a sandbank.

The significance of the removal of the Greater Codling Bank as a sandbank lies in the fact that, at a stroke of a pen, the total national resource of the habitat was slashed by 50%. Meaning that instead of having to designate between 104-311km2 as SAC, the state now only had to designate between 49.4-148.2km2.

A document seeking Ministerial approval to proceed with advertising the designation proposals in November 2012 states:

“A total of 7 sites[4] (comprising 343,562 hectares) were recommended initially for designation but this has now been reduced to 6 due to the findings of the recent Codling Bank survey (October 2012) which found that a considerable portion of the Codling Bank area does not fall within the definition of the Annex 1 habitat, sandbank. As a result, the estimated national area of sandbank has been revised downwards substantially.”

The site that had been removed was the Kish/Bray Bank.

The same document says that:

“The Kish Bank has now been removed from the areas proposed for designation… […] It is anticipated that the Kish Bank will be designated as a Special Protection Area [SPA] for birds in the future.”

An SPA is a separate type of designation, under the EU’s Birds Directive, and this statement acknowledges the importance of the Kish Bank for foraging sea birds. However, despite this, no SPA designation was forthcoming.

Hempton’s Turbot Bank

Records reveal:

“The proposed designation of Hempton’s Turbot Bank [Donegal] and the Blackwater/ Lucifer Banks [Wexford] will satisfy Ireland’s obligation to designate between 20-60% of its sandbank resources. These proposed sandbank habitats provide c 45% of Ireland’s overall sandbank resource, which will bring Ireland well within the 20-60% range required by the Commission.”

It is not clear how this 45% figure was derived. You’ll also note that Hempton’s Turbot Bank in Donegal is mentioned here, but surveys showed that this site was predominantly below the 20m depth needed to meet the EU definition for sandbank habitat. While there is an allowance for depths greater than 20m, this means that, at the least, Hempton’s Turbot Bank would be a poor example of sandbank habitat based on this criterion and probably did not warrant designation.

Indeed, in 2019, the NPWS went so far as to say:

“It is considered that the habitat within this SAC [Hempton’s Turbot Bank] is not fully characteristic of the Sandbanks which are slightly submerged by sea water all the time habitat [sic] as described in the EU Interpretation manual”.[5]

An internal email thread showed that this concern was raised within the department in 2013.

Furthermore, an agenda for an internal meeting of NPWS staff in February 2013 sought to raise the point: “Is Hempton’s Turbot Bank a valid sandbank site?” The minutes of this meeting have not been released to Coastal Concern Alliance. Nevertheless, the designation went ahead in spite of the doubts that had been raised.

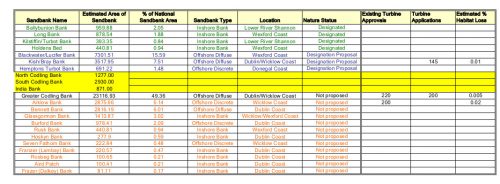

Many of the NPWS records make reference to wind farms. One of these shows a table of all the sandbanks along with their areas and, significantly, those with wind turbine applications. Why was this relevant? Once again, we see wind energy interests highlighted in a process that should have been purely based upon scientific evidence. Both the Greater Codling Bank and the Kish/Bray Bank are marked on this table as having “turbine applications”.

A record releasee to Coastal Concern Alliance listing all the sandbanks, but also referencing those with wind turbine applications

Another record justifying the designation of the Blackwater Bank and the Hempton’s Turbot Bank describes them as “pristine”, despite the doubts that had been raised as to whether or not the latter site even qualified as a sandbank, and that:

“there are no operant or expected pressures at either site that would compromise the long-term sustainability of the habitat feature. (This is not true for Kish/Bray Bank as there is an option on a Foreshore Lease in relation to the Dublin Array Wind Park).”

Tensions over the designation of new marine SACs (not only for sandbanks but for other features such as bottle-nosed dolphins) are clear in the records. Bord Iascaigh Mhara, concerned over potential constraints on fishing activity in any of the new SACs, noted in 2012 that:

“The terms of the consultation indicate that adjustments to boundaries can only be made on scientific grounds. Without habitat maps or in the case of mammals, habitat usage/ residence data then it is nigh impossible to make any submission on scientific grounds. It is not a consultation if those being asked to submit are not in a position to influence the result; It is an information giving exercise. This applies to both the public and the state agencies submissions.”

However, it seems clear from the records that some were in a position to influence the result. It seems clear to us that the interests of the wind energy industry were taken into account when drawing boundaries, in particular in the removal of the Kish/Bray Bank SAC and the Greater Codling Bank altogether, in contravention of EU rules.

Wind Farms

There is a clear and urgent need to decarbonise our economy and the development of offshore wind can, and should, make a significant contribution to this.

However, in May 2019 the Dáil declared a climate and biodiversity emergency, so it is essential that in addressing one crisis we do not exacerbate another (see here for an IWT blog on this topic). Wind turbines can impact sandbanks both directly (through the removal of the habitat to make way for concrete plinths) and indirectly (through changing the currents around the plinths which in turn could affect how the sand is eroded or deposited elsewhere). They can also impact birds either directly (by collision with turbine blades) or indirectly, e.g. by forcing birds to avoid important feeding grounds.

The potential for wind turbines to impact sandbanks was acknowledged in 2007 when the NPWS delivered their first report to the European Commission on the status of protected habitats and species under Article 17 of the Habitats Directive, noting:

“The potential aggregate extraction, coal extraction and windfarm development remain a threat to the integrity of sandbanks.”

This report assessed Overall Future Prospects: “Unfavourable – Inadequate”.

Also:

“From the large number of sand banks that have been investigated for their suitability for wind farms and their potential as sites for aggregate extraction the future prospects are considered to be Unfavourable – Inadequate”[6].

However, in the third round of reporting, in 2019, the NPWS said there were “no pressures” and “no threats” to the status of sandbanks in Ireland although also stating that “the development of windfarms on shallow sandbanks has the potential to lead to an indirect impact on the habitat”.

Why the threat is now only ‘indirect’ is not clear. The NPWS went on to assess the status of sandbanks as “favourable” although adding that:

“The conservation status of this habitat is Favourable but it is vulnerable to the potential impacts of wind energy infrastructure in the vicinity of the habitat.”

Despite this, the NPWS said that ‘future prospects’ for the habitat were ‘good’[7]. No rationale is given for the reclassification of the future risk to sandbanks associated with wind turbines. Why did the NPWS change their assessment between 2007 and 2019? A satisfactory answer to this has not been forthcoming.

EU Compliance

Today, having excluded the Greater Codling Bank, the NPWS gives the total area of sandbank in Ireland as 247km2. The area of habitat within the four SACs is given at 68.68km2, which means c.28% of the resource is officially protected, thereby falling within the 20-60% band looked for by the EU, albeit at the lower end[8]. This is much lower than the 45% for the two proposed sites (Hempton’s Turbot Bank and Blackwater Bank) previously claimed by the NPWS.

The lack of any SACs north of Wexford has led to a gaping geographical gap in the distribution of SACs for sandbanks, one that would have been filled with the designation of the Kish/Bray Bank.

The dubious exclusion of the Greater Codling Bank and the equally dubious inclusion of Hempton’s Turbot Bank have dramatically skewed the figures meaning that the real level of protection is below the lower 20% threshold. Ireland is, therefore, unlikely to be compliant with the Habitats Directive and therefore needs to designate more sandbank SACs.

Based on all of the above, Coastal Concern Alliance has made a formal complaint to the European Commission. The Commission have acknowledged receipt of the complaint and have confirmed that an investigation in underway

A number of additional related issues became apparent during the course of the group’s investigation and more information will be released as soon as findings are verified.

Marine Protected Areas

Ireland has been hopelessly behind in the push to designate, and actually protect, areas of the marine environment within MPAs. The SACs and SPAs that have been designated fall within the mere 2.1% of our seas that today qualify as MPA (the target for 2020 was 10%, the target for 2030 is 30%).

Sandbank habitats are vitally important for the protection of marine biodiversity as well as for providing protection of the coast along the east of our island where erosion is already a serious issue. We haven’t begun to appreciate the value of these systems in the face of rising sea levels and more extreme, and frequent, weather events.

A number of records released to Coastal Concern Alliance reference wind turbine applications

Conclusions

That the NPWS has been weak and ineffective in protecting of our natural environment comes as no surprise. Despite this, many valiant souls within it have fought to retain their integrity in the teeth of pressure from outside forces. But this pressure has been intense and unrelenting.

Thanks to the persistence of Coastal Concern Alliance – a voluntary citizens’ group – an insight into this unhealthy dynamic has been revealed. While fishers and farmers where having designations imposed upon them with no account taken for their livelihoods (although, admittedly, this has barely impacted upon fishers due to the near absence of meaningful conservation measures in marine SACs and SPAs) the well-connected wind industry were in a position to exert influence. It seems that swift and creative measures ensured that designations for nature conservation would not impede their freedom of manoeuvre.

However, we also see here a dark side to the NPWS. The records suggest to us that there was a willingness to massage scientific data, or actively ‘find’ data in order to produce an outcome designed to relieve the outside pressure – as was shown with the removal of the Greater Codling Bank through the tendering of a hasty survey and its subsequent delisting as a sandbank at the stroke of a pen.

We also see the corresponding ‘upscaling’ of Hempton’s Turbot Bank to “pristine” despite concerns being raised that it didn’t even qualify as sandbank habitat. This places the credibility of the NPWS, heretofore trusted for its scientific integrity, in question.

The findings also impede our efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as it will inevitably delay proposals to build wind farms on sensitive habitats in the Irish Sea. The government has already ignored pleas from conservation organisations for sensible marine spatial planning and, in particular, to identify locations of MPAs before, or at a minimum in parallel with, the planning of offshore wind (see here for an IWT blog on this subject).

The IWT, which is privileged to have been given access to the records released to Coastal Concern Alliance, is deeply concerned about the way in which concerns for the wind industry seem to have undermined nature conservation efforts. We are happy to learn that the European Commission is investigating the matter but we also know how the wheels of this bureaucracy move very slowly.

What next?

In light of these investigations, we are calling on the government, and in particular Minister Malcolm Noonan, who has responsibility for the NPWS within the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage, to launch an internal investigation into the matter. Most importantly, this must look at the adequacy of SAC designations for sandbanks in the Irish Sea.

In our view, there is a clear need for additional designations, particularly the Kish/Bray Bank, which is the best example of the habitat according to the NPWS’s own data.

We also need to have faith in the NPWS scientific and designations units. We need to know that the science is not going to be compromised by political or economic interests. To help to restore confidence, a review of all the data on sandbanks needs to be carried out in an open and transparent manner. In addition, fresh surveys need to be carried out, using reliable methodology, for example using underwater cameras, rather than relying solely on grab samples of sediment.

The protection and restoration of biodiversity must be done in tandem with decarbonisation. We do not accept that biodiversity should be sacrificed as part of our effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

[1] Marine Habitat types definitions. Update of “Interpretation Manual of European Union Habitats”

[2] Roche, C., Lyons, D.O., Farinas Franco, J. & O’Connor, B. (2007) Benthic surveys of sandbanks in the Irish Sea. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 29. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Dublin, Ireland.

[3] October 2012. Aquafact International Services Ltd. Subtidal Benthic Investigations of the Greater Codling Bank.

[4] Not all the proposed sites for designation were for sandbanks

[5] NPWS (2019). The Status of EU Protected Habitats and Species in Ireland. Volume 2: Habitat Assessments. Unpublished NPWS report. Edited by: Deirdre Lynn and Fionnuala O’Neill

[6] 2007. The Status of Protected Habitats and Species in Ireland. Backing Documents, Article 17 forms, Maps. Volume 1.

[7] NPWS (2019). The Status of EU Protected Habitats and Species in Ireland. Volume 2: Habitat Assessments. Unpublished NPWS report. Edited by: Deirdre Lynn and Fionnuala O’Neill

[8] This figure is calculated from the Conservation Objectives documents for each of the four SACs