There’s a corner of the Phoenix Park, Dublin’s largest open space, that hints at wildness. It’s different from the rest of the Park in that it’s less manicured, messy looking, with unmown meadows and patches of scrubby thorn bushes. Most people walk right past it but within its tangled undergrowth there are fallen giants: great ash trees that have been toppled, perhaps many years ago. The crown of the trees have created a cage of branches, making access difficult for deer, and so patches of brambles have grown up. Brambles are among our most important plants for wildlife and provide the dense cover needed for our smaller songbirds to nest in.

A burrow under a heavy trunk looks a little small to be a fox den, maybe it’s a rabbit’s or a stoat’s. Fungi are sprouting from the rotting dead wood and gently lifting an old layer of bark reveals colonies of woodlice, centipedes and spiders. Intricate patterns on sapwood tell us that grubs of beetles and weevils make a living in the wood itself – if there were woodpeckers in the Park they’d be hammering away trying to get at them. When big trees fall over they create a cavity in the ground where the roots were and this typically fills with water, creating a mini wetland for frogs and aquatic bugs. Over a century or more the breaking down of dead wood recycles nutrients back into the soil, but for many trees falling over does not mean death. They simply send new shoots skyward and carry on as before. This has happened to one of the fallen trees in this area.

Revealingly, a rough path has been trampled to one enormous trunk where a ‘saddle’ has been worn smooth and shiny from children eager to climb on it.

Fallen trees frequently are not dead but send out new shoots

Despite the immense value of fallen trees and dead wood, our obsession with tidiness means that this entire phase of a tree’s life is normally sawn up and carted away. This is a feature all over Ireland and what is unusual about the corner of the Phoenix Park that I have just described is that it exists at all. Virtually every other corner of the Park is meticulously manicured to such a degree that it actively prevents even common wildlife from gaining a foothold.

Life thrives on dead and fallen trees

Last week it was brought home to me just how fastidious the authorities in the Park have become. Strong winds had toppled a large beech tree, probably on the Friday night. I cycled past it on the Saturday and on the Sunday I paid another visit. The trunk had snapped off completely, revealing a hollow interior that had been colonised by some kind of fungus. It fell on the high side of the hill, away from the nearby path and on a sloped area which has rough grass. I emailed the Park authorities on my return suggesting that it was not a hazard to anyone and asking that it be left where it lay. On Monday I got a reply thanking me for the email and promising to look into my request. By Thursday the tree was gone. Apart from the jagged stump, the whole thing had been tidied away – it looked to me that even the leaves had been swept up. Why is this habitat destruction still going on?

It took a mere 5 days to tidy away all trace of this tree

Don’t get me wrong, I love the Park. I love the size of it – I still find that I’m discovering new nooks and hidden corners. It has amazing trees, particularly oaks but also beeches, chestnuts and pines. It also has wildlife in it: foxes, grey squirrels and, of course, the deer. A biodiversity survey by Trinity College on the grounds of Áras an Uachtaráin, initiated by the president himself, found a rare specimen of a cave spider as well as a family of badgers. I love to see (and hear) the jays, because they don’t normally hang around the kind of housing estate that I live in. In summer there are nesting skylarks near the 40 acres and it’s wonderful that we still have their uplifting song in the heart of the city. But by and large the Park fails to live up to its potential.

The red squirrels and corncrakes went extinct from it in the 1980s. I don’t remember there ever being hares or barn owls although it seems perfect for them. During the summer just gone I spent a few moments on a warm day sitting in one of the vast expanses of grassland and saw not a single butterfly or flying insect. The birdlife is mostly magpies, rooks, pigeons and jackdaws, with a few mallard and heron on the ponds. There’s more of course but the gardening mindset of the OPW, which manages the Park, is holding it back. It could be so much better.

Vast grasslands with few wild flowers or flying insects

Imagine for a moment that they let the trees just lie on the ground. Immediately you introduce a layer of complexity that simply isn’t there right now. Imagine the existing wooded areas were fenced off from the deer, new scrub and young trees would emerge – introducing another layer of complexity. When the OPW plant new trees, incredibly they’re still planting non-native species, including holm oak, a Mediterranean tree that is useless for wildlife in Ireland.

We can keep the historic character of the Park and I’m not suggesting that it be rewilded in its entirety. We don’t have to convert any of the open grasslands to new woodlands – just manage what’s there differently. The grasslands are dreadfully species-poor, but the OPW seem very resistant to adding diversity for pollinators and other insects, in the belief that the deer will only eat the flowers. This doesn’t make sense. Their outdated conservation plan says that a ‘strategic objective’ is to “conserve the Phoenix Park’s natural plant and animal species along with their habitats while improving biodiversity”. But they don’t seem to be doing anything to improve biodiversity – quite the opposite. It is in their plan to create new native woodland, to allow dead and fallen trees to stay and to fence off areas from deer – but I don’t see any evidence of this on the ground.

The amazing difference a fence makes – but this fence has a gap in it so is no longer effective

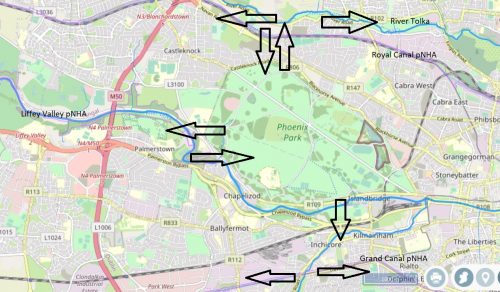

What about bringing lost species back? The pine marten is making its way up the Liffey valley but will need to cross one of the busy roads to get to the Park. Shouldn’t we be building a wildlife bridge to make it easy for them? If they make it, and presuming they start to control the grey squirrel population, can we bring back red squirrels? Could we reintroduce goshawks (a large bird of prey), corncrakes or one of the many species of deadwood-dependent beetles which have gone extinct from Ireland?

The importance of rewilding in addressing the climate and biodiversity emergency is now a mainstream idea. One of the reasons I love it is that it’s for everyone, whether you live in the city or the countryside. The Park is great but it’s not unique, there are acres and acres of near-sterile green spaces in Dublin and, no doubt, other towns and cities in Ireland. Can we rewild them all? There’s nothing stopping us trying if we can only let go of our urge to tidy everything up all the time.

We could create wildlife bridges and corridors to allow animals move around the city